Jupiter reaches its best apparition in a decade for northern observers and offers a wealth of detail. Joining in late evening is brilliant Mars, now a month from opposition. Saturn is visible in the early evening, along with Venus soon after sunset. Uranus and Neptune remain visible with binoculars, and Mercury makes a fine morning appearance.

Venus shines brilliantly shortly after sunset. It starts the month in eastern Sagittarius at magnitude –4.2. The crescent Moon stands less than 3° due south of Venus on the 4th.

Venus enters Capricornus Dec. 6 and stands north of Delta (δ) Capricorni on the 28th. The planet reaches Aquarius by the 31st.

Follow the changing phase of Venus with a telescope. On the 1st it shows a 67-percent-lit disk 17″ across. By year’s end, the disk grows to 22″, while the phase drops to 55 percent.

As soon as it’s dark, Saturn is 40° high in the south, among the stars of Aquarius. It shines at magnitude 0.9 and dims 0.1 magnitude by midmonth. The planet is about 2° southeast of Lambda (λ) Aquarii, and stands 4° northeast of a seven-day-old Moon Dec. 7. Saturn sets shortly before midnight on the 1st and by 10 p.m. local time on the 31st, so try to observe it in the two to three hours after sunset.

Through a telescope, Saturn’s disk spans 17″. The rings span 38″, while the minor axis is a mere 3″.

Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, is 8th magnitude — an easy target for any telescope. It is near the planet Dec. 5/6, 13/14, 21/22, and 29/30. Tenth-magnitude Tethys, Dione, and Rhea congregate close to the rings and occasionally pass in front of or behind the disk. High-speed video may capture these events.

On the 11th, Rhea begins a transit at 9:30 p.m. EST, followed four minutes later by Tethys. Tethys’ shadow appears about 40 minutes after it. Rhea exits the disk around 10:30 p.m. CST and Tethys follows at 11:20 p.m. CST (note the change to CST, as Saturn has set on the East Coast).

Look for three of Dione’s transits: One on the 4th begins at 9:17 p.m. EST and lasts about 2.7 hours. A repeat occurs on the 15th, starting soon after 9 p.m. EST, and again on the 26th just before 8 p.m. EST.

Iapetus reaches inferior conjunction Dec. 10, when the 11th-magnitude moon is 45″ due north of Saturn. The next night, it is 1′ northwest of the planet. It continues west, brightening to magnitude 10 on the 31st, when it reaches western elongation 8′ west of Saturn.

Neptune ends its retrograde path on the 8th. You’ll find the magnitude 7.8 planet with binoculars, just a Moon’s width northwest of magnitude 5.5 20 Piscium. This star lies at the western end of a line of three stars of similar brightness, all 5° to 7° southeast of Lambda Psc. Neptune sets before midnight in late December. The distant planet lies 4° northeast of the Dec. 8 First Quarter Moon.

Uranus spends December about 7° southwest of the Pleiades (M45). A waxing gibbous Moon stands 4.5° northwest of Uranus on the 12th. The planet is an easy object in binoculars at magnitude 5.6, fading only 0.1 magnitude throughout the month. A telescope shows its 4″-wide disk.

In early December, Uranus tracks south of a 7th-magnitude field star, which is 2.5° southeast of 5th-magnitude Tau (τ) Arietis. Binoculars will easily show 4th-magnitude Delta and Zeta (ζ) Ari forming a triangle with Tau. The ice giant is visible until well after midnight all month.

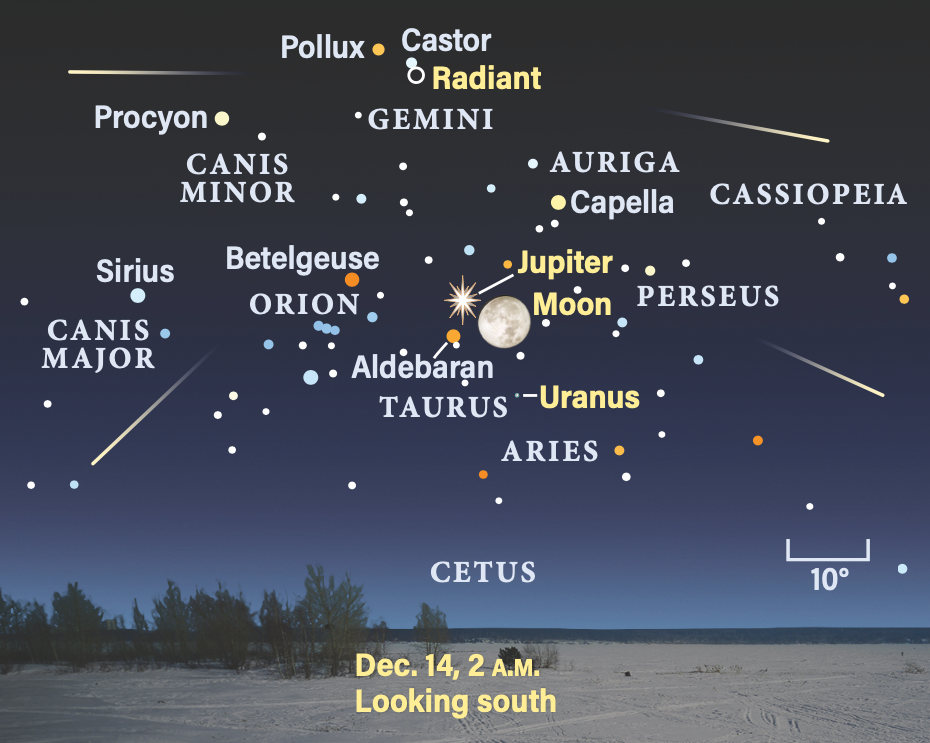

Jupiter reaches opposition Dec. 7. It rises around 5 p.m. local time on Dec. 1 and is visible all night. The giant planet is at its best for a decade for Northern Hemisphere observers.

Located in Taurus, Jupiter climbs to 70° altitude at local midnight for mid-latitude U.S. observers. At magnitude –2.8, it dominates a sky already brilliant with winter constellations The planet wanders west, ending the month 6° northeast of Aldebaran. A near-Full Moon stands 10° northwest of Jupiter on the 13th; M45 lies 6° west of the Moon on this evening. The next night, the Moon is 7° northeast of Jupiter.

A small telescope reveals a few details on the disk, which spans 48″. Moderate (100x–

150x) magnification shows a pair of belts straddling the equator. The equatorial region rotates in nine hours and 50 minutes, while higher latitudes take five minutes more, resulting in violent storms at the interfaces. The churning atmosphere provides constantly changing features. A full rotation can be observed in a night.

Occasionally the Great Red Spot is visible, plus the dusky northern and southern polar regions. Larger telescopes (8 inches or greater) reveal even more. Higher magnification increases the effect of atmospheric turbulence on the image, so don’t overdo it.

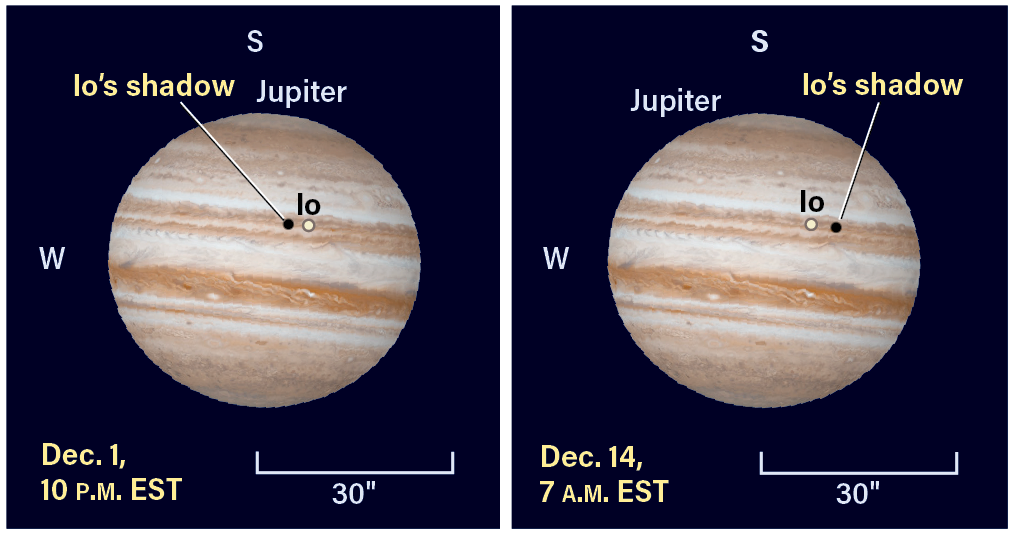

Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto orbit every two to 17 days. The innermost three moons are locked in a 1:2:4 resonance, so their relative positions repeat. The moons also transit in front of or become hidden behind the disk. Here are some, but not all, of the month’s events: Io and its shadow transit the disk on the evening of the 1st. The shadow appears on Jupiter’s eastern limb at 9:02 p.m. EST, leading Io by only 10 minutes. It’s one week before opposition. Watch again on the morning of the 14th, a week after opposition, when the transit repeats. This time Io leads, starting at 6:13 a.m. EST; the shadow follows 10 minutes later.

Io is occulted on the 16th, around 10 p.m. EST — plan to be watching at least 10 minutes before this to locate Io off the western limb of the planet and catch the disappearance.

Europa and its shadow transit Dec. 12/13, beginning at 12:31 a.m. EST (the 13th in the Eastern time zone). The shadow follows just under 20 minutes later — a bigger difference than Io and its shadow, although we’re only five days past opposition. This is because Europa orbits farther from Jupiter.

On the 15th, Ganymede begins a transit just before 8:50 p.m. EST, followed by its shadow at 9:37 p.m. EST. For over an hour, moon and shadow cross the dusky southern polar region, until Ganymede leaves around 10:55 p.m. EST.

There’s a repeat Dec. 22/23, moments after midnight in the Eastern time zone. Ganymede’s shadow appears some 95 minutes later, half an hour before Ganymede leaves the disk.

Callisto avoids the disk altogether; overnight on Dec. 3/4, you can catch this moon due south of Jupiter.

Mars opens the month at magnitude –0.5 and brightens to magnitude –1.2 by the end of December. We are a few weeks from its January opposition.

Mars rises at 8:30 p.m. local time on the 1st and stands more than 30° high in the east by midnight, in the constellation Cancer. It outshines nearby stars Procyon, Castor, and Pollux.

Mars halts its rapid easterly motion on the 7th and begins a retrograde loop 2.3° north of the Beehive star cluster (M44). A waning gibbous Moon lies within 0.9° of Mars Dec. 18. The Red Planet ends the month less than 9° southeast of Pollux.

Through a telescope, Mars’ disk begins to reveal more features. It hits 13″ in diameter by the 10th, and 14″ by the 21st. Its phase grows from 93 percent to 99 percent lit during December.

Mars’ rotation period of 24.6 hours means that if you observe at the same time each night, features appear to wander backward. About 25 days show a full rotation. The following are visible at local midnight on (and a few days on either side of) the given date from the central U.S.: Dec. 1, Tharsis Ridge; Dec. 5, Valles Marineris and Solis Lacus; Dec. 8, Mare Erythraeum; Dec. 13, Sinus Meridiani; Dec. 20, Syrtis Major and the Hellas basin; Dec. 27, Mare Cimmerium; Dec. 31, Mare Sirenum. If you pick a date, say the 20th, then Sinus Meridiani, previously visible at midnight on the 13th, will reach the center of the disk four hours later, at 4 a.m. local time.

The best images are acquired using high-speed monochromatic video cameras with RGB and IR filters. Practice now, before we reach opposition.

Mercury quickly appears in the morning sky after its Dec. 5 inferior conjunction. It reaches 1st magnitude by the 12th and is 3° high in the east 50 minutes before sunrise. Mercury brightens to magnitude 0 by the 18th, climbing to 6° in elevation an hour before sunrise. A telescope shows a crescent disk growing to 50 percent lit by Dec. 20 and spanning 7″, then becoming a gibbous through the end of the year, while its apparent diameter shrinks to 6″.

On Dec. 21, Mercury stands 7° due north of Antares (the star is hard to see in twilight — try binoculars). Greatest western elongation occurs on the 26th, with Mercury at magnitude –0.3 and 22° west of the Sun. On the 28th, the waning crescent Moon rises alongside Mercury. They stand 9° apart and rise shortly after 5:30 a.m. local time. Depending on location, you may catch the Moon passing 0.7° south of Antares. Thirty minutes after they rise, they are more than 3° high in a dark sky — you’ll need a very clear southeastern horizon.

On the last day of 2024, Mercury rises one hour and 40 minutes before the Sun, clearly visible in the predawn sky.

Rising Moon: Sunrise scarp

The Straight Wall is the best-known scarp feature on Luna’s frontside, an outstanding treasure in the form of a long black blade extending outward from its bejeweled hilt. It is perfectly placed on relatively flat lava near the center of a large, half-buried crater on the southern third of the Moon, appearing just after First Quarter. Find this fault in the terrain on Dec. 8 just north of the bright highlands that include magnificently rayed Tycho.

Although its very name conjures images of a cliff, in fact the Straight Wall has a modest slope between 12° and 20° — a decent grade for driving, but not enough for tobogganing. Officially labeled as Rupes Recta in many lunar atlases, it is 75 miles long and rises some 1,300 feet above the plain. The scarp likely formed when Mare Nubium’s lava-flooding episode ended, the terrain sinking and pulling westward away from the land to the east. You’ll see Mare Nubium on the following night.

Thanks to the extent of the shadows on the 8th — longer than those in the accompanying image — the intriguing feature Rima Birt is also ripe for viewing. It won’t be easy to see this worming channel extending north of the crater Birt, so use some patience and the highest power the atmosphere will allow to trace out the groove, likely carved out by once-running lava. Watch Birt’s shadow retreat during a two-hour session.

Meteor Watch: Low chances

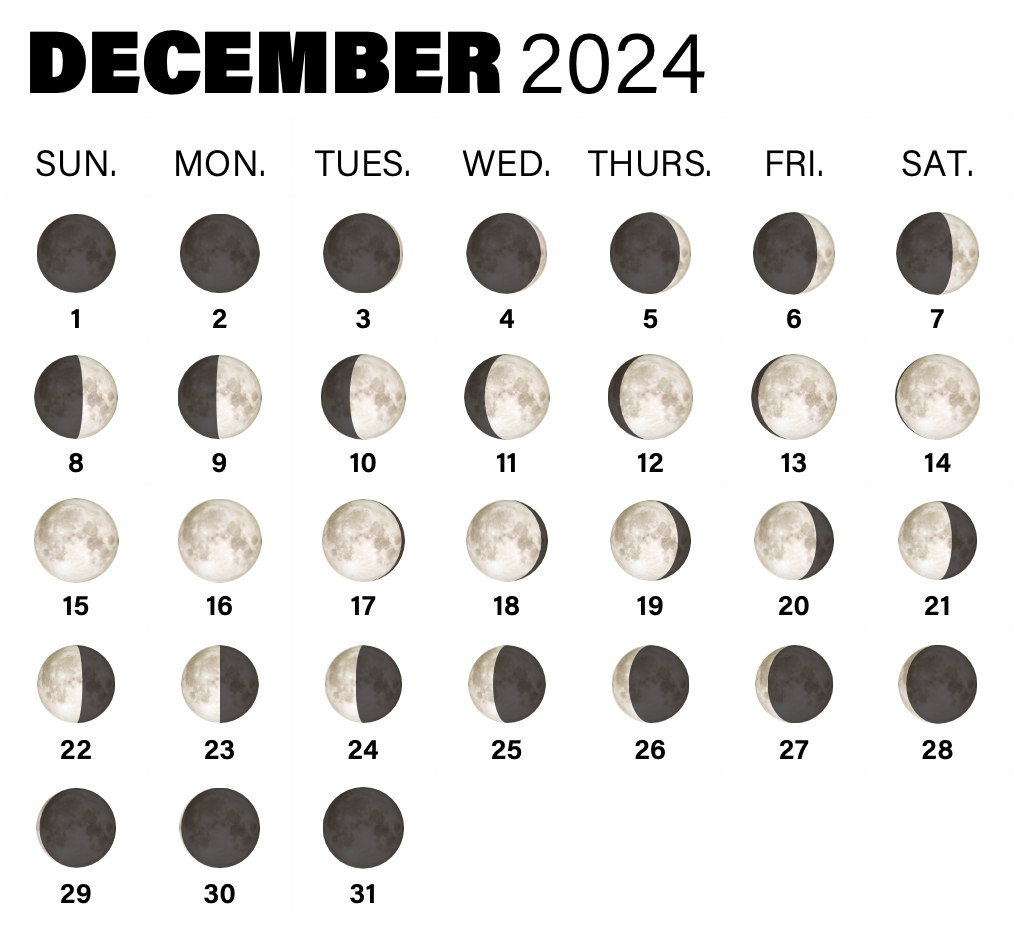

Two major meteor showers occur in December. The Geminids are active between Dec. 4 and 20, and peak late on Dec. 13. A nearly Full Moon on the peak night interferes strongly with this shower. Some Geminids are particularly bright, and will show up in a moonlit sky, although much lower rates than those advertised will be experienced.

More favorable this year are the Ursids, with a peak coinciding with a Last Quarter Moon. The Ursids are active between Dec. 17 and 26, and peak early on the 22nd. The radiant, located in Ursa Minor, is visible all night. The Moon rises around local midnight, so late-evening observing will offer dark skies. However, rates are low, with no more than a half-dozen to a dozen meteors visible in an hour period.

Comet Search: Soaring in sinking Aquila

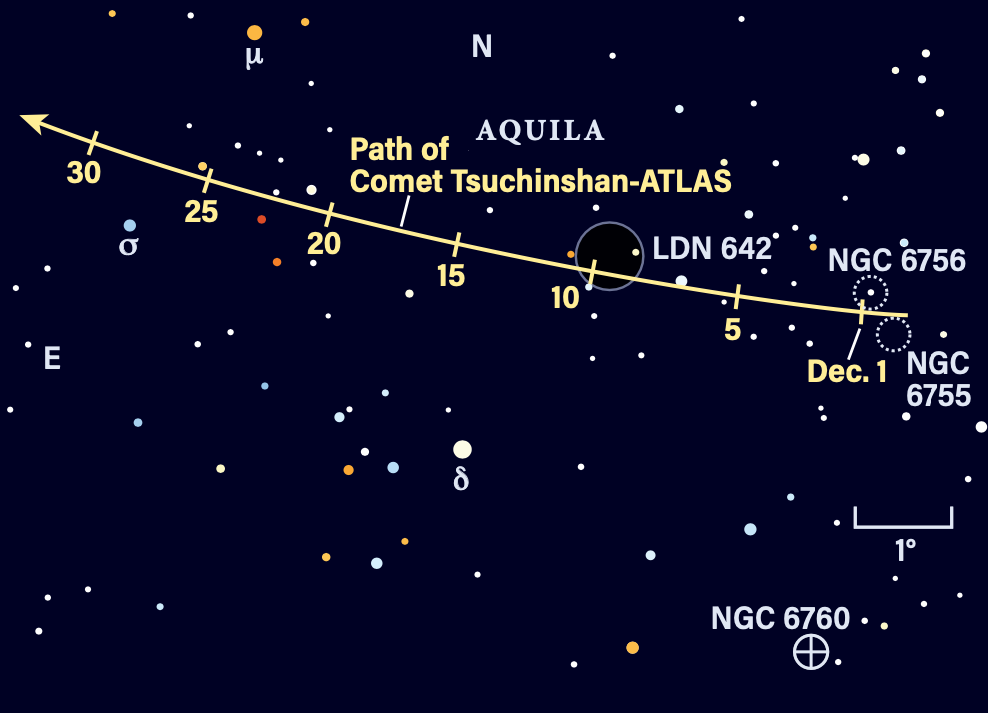

To watch the end of Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS)’s story, be prepared at the eyepiece 90 minutes after sunset. Dropping to the horizon and out of easy binocular range, 8th-magnitude Tsuchinshan-ATLAS demands a country sky to the west with a clear horizon.

Its diatomic carbon emission shuts down near December’s end due to increasing distance from the Sun. The celestial snowball floats in front of the dust cloud LDN 642 on the 9th and 10th.

Visually, the comet will draw your attention to star clusters NGC 6755 and 6756 as December opens. Try different magnifications and sweep around. These sparse groupings aren’t at all cometlike, so swing to nearby globular NGC 6760 to compare shape, brightness profile, and edge softness with Tsuchinshan-ATLAS.

When the evening dark window reopens on the 20th, turn your sight to softly glowing Comet 333P/LINEAR, brighter than M102 in Draco. You’ll need several finder charts or an app for short-period LINEAR (8.7 years), since it launches from the Hunting Dogs, passes near Alcor and Mizar, then flies over the Dragon to reach the Swan, unfortunately missing many big-name objects.

Locating Asteroids: Sharing the chariot

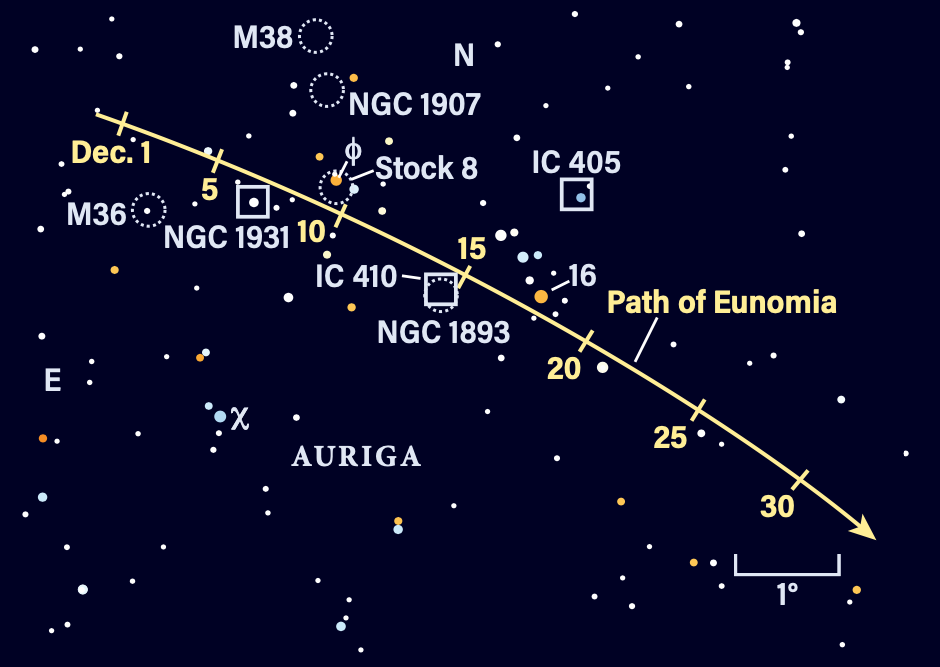

Rising in the northeast along with Jupiter during the evening hours, asteroid 15 Eunomia slides through object-rich central Auriga while outshining most of the background stars.

Peaking at magnitude 8.1, about the brightest it can possibly get, Eunomia is a straightforward target to follow across the fainter outer spiral arm of the Milky Way. In fact, none of the stars in the splashy star cluster M36 (less than a degree to the south) are brighter. On the 7th, Eunomia shares a medium-power field with the reflection nebula/mini-cluster combo NGC 1931, one of the sky’s best comet lookalikes.

The 18th is the best night to see the space rock move relative to the background, sliding less than 10′ from 16 Aurigae, which shines at magnitude 4.5. An 8th-magnitude field star to the southeast provides an anchor to reveal the asteroid as the trio forms a crooked line that straightens and then re-kinks in under two hours.