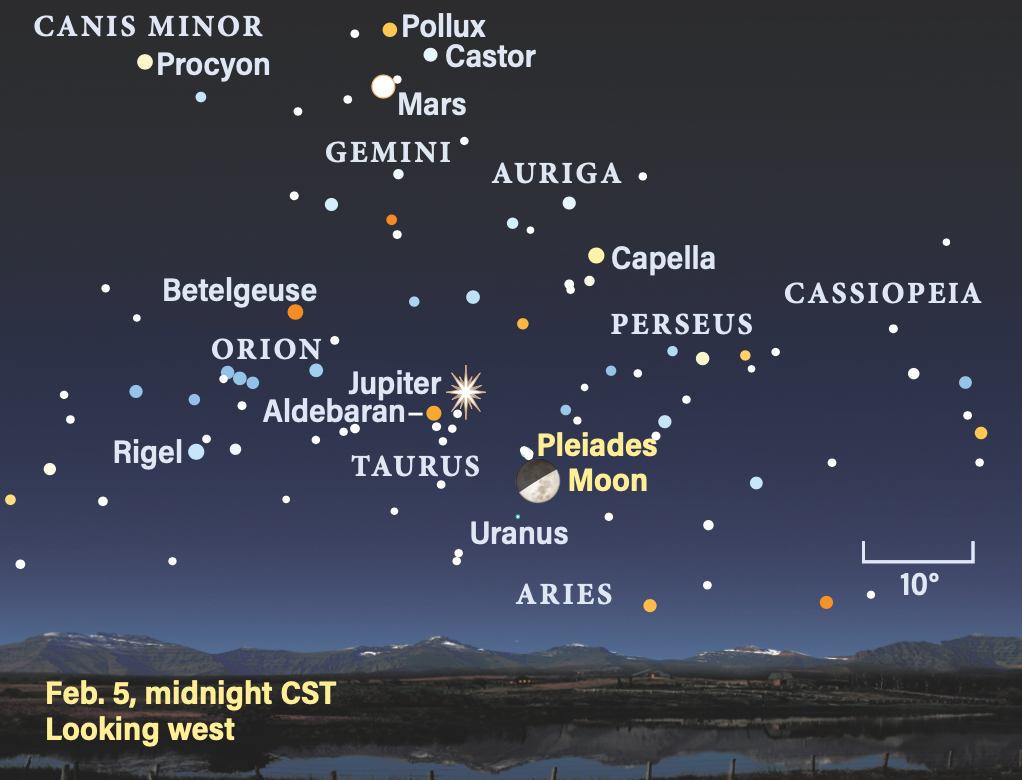

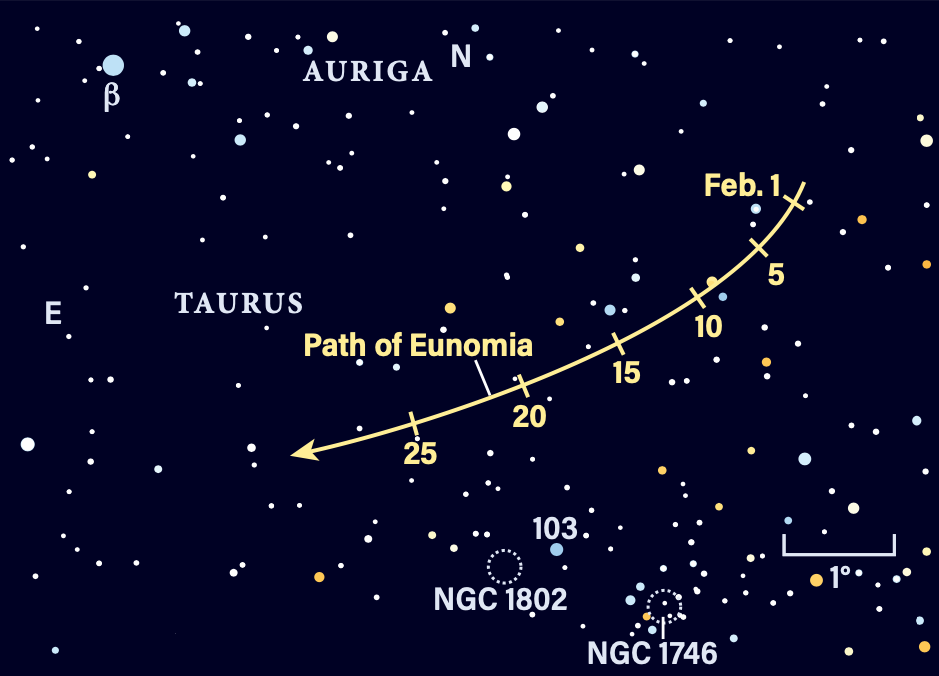

We’re quickly losing sight of Saturn, but Venus, Jupiter, and Mars dominate the sky. Uranus and Neptune are easy binocular objects. Mars is still at its best, having reached opposition last month. Jupiter has many satellite transits visible in small telescopes. And early in the month, the Moon passes in front of the Pleiades, visible from the western U.S.

Saturn appears low in the southwest at dusk and drops quickly from view, setting within three hours of sunset on Feb. 1. It descends each consecutive day and is 8° high an hour after sunset on the 15th, glowing at magnitude 1.1. The rings are very narrow — this is your last glimpse of them before the ring-plane crossing next month, which will be hidden by the Sun. The angle of the rings drops from 2.8° to 1.3° during February and they become a difficult feature to observe due to low altitude and twilight.

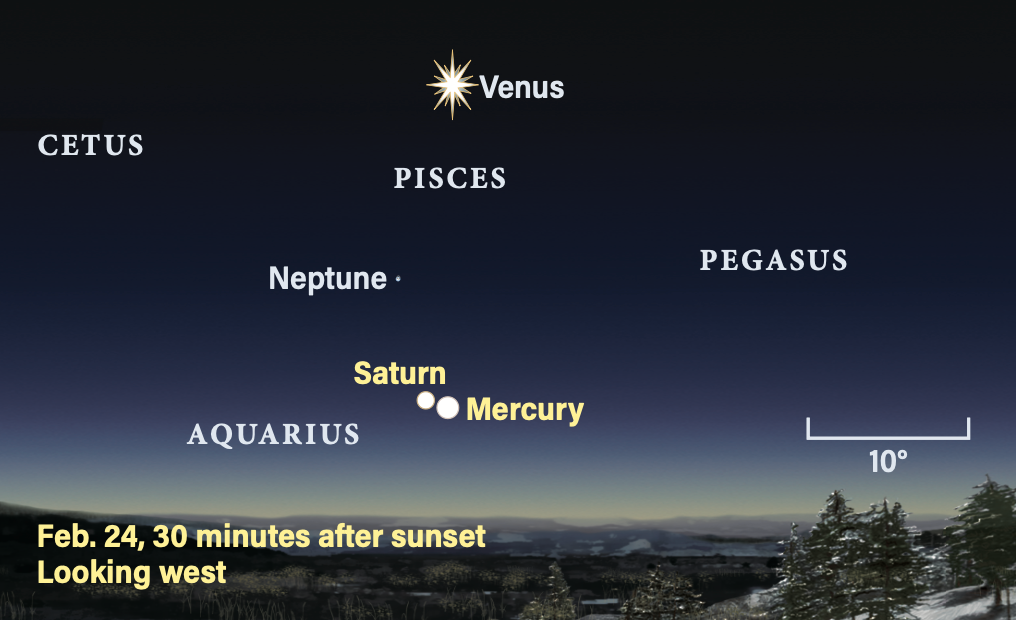

Mercury reaches superior conjunction with the Sun on the 9th and isn’t visible early in the month. The small planet comes up to meet Saturn on the 24th, when they stand side by side. Start looking 5° high in the western sky 30 minutes after sunset. Mercury is brighter, at magnitude –1.3, with Saturn 1.5° to its left. Binoculars are best to visually capture this scene. Magnitude –4.9 Venus stands 22° degrees above the pairing, guiding your eye down to the horizon and the two fainter planets. You only have 30 minutes or so to see them before they set. Saturn is lost from view soon after this as it heads for conjunction with the Sun.

By contrast, Mercury climbs higher in the sky. On the 28th, a slender, one-day-old Moon greets the planet. The two stand 3° apart. Can you see the Moon? It’s challenging to spot so soon after New. You’ll need a western horizon free from obstructions as well as a clear sky with little haze. Through a telescope, Mercury reveals a 76-percent-lit disk spanning 6″.

As Mercury and Saturn tussle for attention near the horizon, brilliant Venus stands well above them. On Feb. 1, a crescent Moon sits less than 3° from magnitude –4.7 Venus in a stunning evening display. Through a telescope, Venus reveals a 37-percent-lit disk, which thins during the month as its orbital path carries it closer to Earth. Viewing the disk is best in early twilight. Follow Venus throughout the month and watch its phase shrink to 15 percent, while its disk grows from 32″ to 49″.

On the 1st, Venus sets more than three hours after the Sun. By the 28th, it sets about 2.5 hours after the Sun. At 8 p.m. local time midmonth, it is 10° high in the western sky among the faint stars of Pisces the Fish.

Mercury reaches superior conjunction with the Sun on the 9th and isn’t visible early in the month. The small planet comes up to meet Saturn on the 24th, when they stand side by side. Start looking 5° high in the western sky 30 minutes after sunset. Mercury is brighter, at magnitude –1.3, with Saturn 1.5° to its left. Binoculars are best to visually capture this scene. Magnitude –4.9 Venus stands 22° degrees above the pairing, guiding your eye down to the horizon and the two fainter planets. You only have 30 minutes or so to see them before they set. Saturn is lost from view soon after this as it heads for conjunction with the Sun.

By contrast, Mercury climbs higher in the sky. On the 28th, a slender, one-day-old Moon greets the planet. The two stand 3° apart. Can you see the Moon? It’s challenging to spot so soon after New. You’ll need a western horizon free from obstructions as well as a clear sky with little haze. Through a telescope, Mercury reveals a 76-percent-lit disk spanning 6″.

As Mercury and Saturn tussle for attention near the horizon, brilliant Venus stands well above them. On Feb. 1, a crescent Moon sits less than 3° from magnitude –4.7 Venus in a stunning evening display. Through a telescope, Venus reveals a 37-percent-lit disk, which thins during the month as its orbital path carries it closer to Earth. Viewing the disk is best in early twilight. Follow Venus throughout the month and watch its phase shrink to 15 percent, while its disk grows from 32″ to 49″.

On the 1st, Venus sets more than three hours after the Sun. By the 28th, it sets about 2.5 hours after the Sun. At 8 p.m. local time midmonth, it is 10° high in the western sky among the faint stars of Pisces the Fish.

Feb. 1 is also a great night to search for Neptune. Later in the evening, Neptune forms a perfect triangle with Venus and the Moon, with each point roughly 2° apart. Neptune is quite faint at magnitude 7.8, but there is a pair of stars (8th and 9th magnitude) near its location. Neptune has a distinctive bluish hue compared to the field stars.

Even 2.8 billion miles from Earth, Neptune shows a 2″-wide disk through a telescope under perfect seeing conditions.

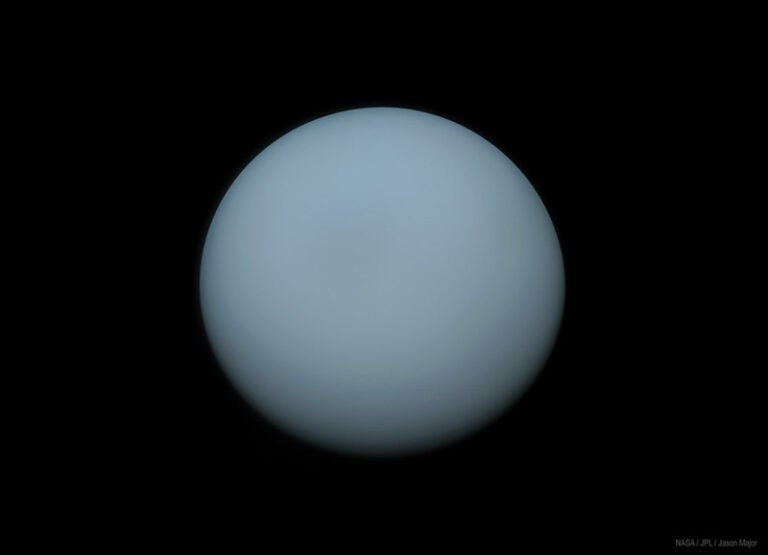

Uranus lies near the border of Aries and Taurus, high in the southeast after sunset. You can find it 2.5° due south of 5th-magnitude 63 Arietis, easily spotted with binoculars 6° southwest of the Pleiades. Uranus shines at magnitude 5.7 through midmonth. Its 4″-wide disk is a challenge, but try under the best conditions with high magnification. Uranus is best viewed well before midnight.

Brilliant Jupiter is high in the sky at dusk, located 5° north of Aldebaran in Taurus the Bull. The distance between Jupiter and Earth is increasing this month, so the gas giant fades by 0.2 magnitude, ending February at magnitude –2.3.

Its retrograde path halts Feb. 4 and the planet resumes easterly motion across Taurus. A waxing gibbous Moon stands 5° north of Jupiter in the 6th, forming a line with Aldebaran.

Jupiter is observable well past midnight, setting after 3 a.m. local time on the 1st and by 1:30 a.m. on the 28th.

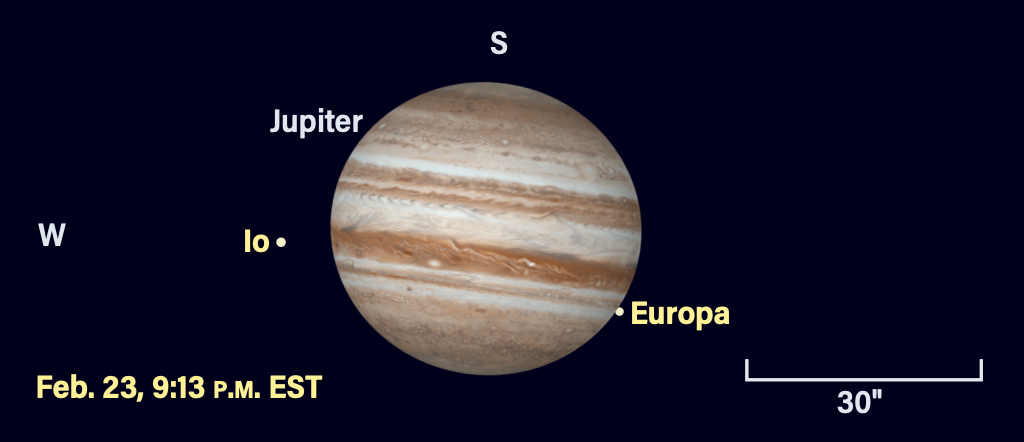

Telescopic views are a delight, showing its dark equatorial belts, four Galilean moons, and occasionally the Great Red Spot. Scopes over 6 inches will reveal finer detail in Jupiter’s dynamic atmosphere, particularly with steady moments of seeing.

Jupiter’s disk spans 43″ on Feb. 1 and drops to 40″ by the end of the month. Its fast rotation (under 10 hours) enables you to see cloud motion within 10 to 15 minutes. Recording details, either on paper or high-speed video, will generate results to keep for posterity.

Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto garner a lot of interest, particularly when they or their shadows transit the disk, or are eclipsed by Jupiter’s great shadow, extending into space behind the planet.

Io and its shadow transit Feb. 1; Io exits by 8:54 p.m. EST, while its shadow leaves at 10:04 p.m. EST. It’s Europa’s turn on the 7th, with the moon transiting at nightfall across the western U.S. The shadow appears on the eastern limb around 9:35 p.m. EST, while Europa leaves the western limb less than 10 minutes later. By 12:10 a.m. EST, the shadow transit ends.

Io repeats its transit on the 8th, starting about 8:35 p.m. EST, followed by its shadow just over an hour later. Note how close the moon and its shadow are compared to Europa the previous night — Io has a smaller orbit. Io leaves the disk at 10:45 p.m. EST and its shadow follows at midnight EST.

The moons repeat Feb. 14/15 (Europa) and 15/16 (Io). Europa’s Feb. 14 transit begins at 8:40 p.m. EST, its shadow following at 12:10 a.m. EST. The moon departs the disk minutes later at 12:13 a.m. EST. On the 15th, Io’s transit begins at 10:26 p.m. EST and the shadow transit begins at 11:43 p.m. EST. Io’s egress is 12:38 a.m. EST, followed by its shadow one hour and 15 minutes later.

On the 21st, Ganymede reappears from behind Jupiter at 8:32 p.m. EST, a process that takes a few minutes. This occurs in twilight across the Mountain time zone and daylight on the West Coast, but the eastern half of the U.S. gets a fine view. Later in the evening, Ganymede enters Jupiter’s extended shadow 28″ off the northeastern limb. The moon begins fading shortly after 11:25 p.m. EST and takes more than five minutes to disappear. How long can you see it?

Callisto is far enough from Jupiter that, from our perspective, it misses the planet entirely. Spot Callisto north of Jupiter in the early evening of Feb. 16.

The 23rd brings a triple event. Io is approaching the western limb around 9 p.m. EST, but turn your attention to the northeastern limb, where Europa reappears from behind Jupiter, but only for a couple of minutes before it enters Jupiter’s shadow. It should be visible between 9:11 p.m. and 9:15 p.m. EST, then fade from view. Io is occulted by the western limb at 9:37 p.m. EST. At 11:54 p.m. EST, Europa reappears from eclipse within Jupiter’s shadow, some 36″ from the northeastern limb.

The night of Feb. 3/4, Ganymede’s huge shadow takes 10 minutes to fully appear on the disk, beginning around 1:30 a.m. EST (on Feb. 4 in the eastern half of the U.S.). Ganymede itself is nearly 30″ from the western limb. Watch the elongated shadow move slowly across Jupiter’s cloud tops. The shadow finally starts its exit around 3:50 a.m. EST.

Mars forms an elegant triangle with Castor and Pollux, Gemini’s brightest stars, on Feb. 1. Shining at magnitude –1.1, Mars stands 4.2° southwest of 1st-magnitude Pollux and 1.8° southwest of 4th-magnitude Upsilon (υ) Geminorum.

Mars is visible all night, climbing above 60° altitude by 9 p.m. local time. Mars continues along its retrograde path into central Gemini until late February. On the 24th, it reverses course and resumes an easterly trek toward Pollux.

Mars’ diameter is 14″ when February opens but diminishes to 11″ by the end of the month.

At 9 p.m. local time from the central U.S. (look an hour later in the east and an hour or two earlier farther west), Mars shows off Mare Cimmerium in February’s the first week. Gradually, at the same time each night, Olympus Mons appears on the western limb. From Feb. 7 to 13, Olympus Mons and the Tharsis ridge move more centrally on the disk.

In mid-February, Valles Marineris is visible. Dark, spidery Solis Lacus is central from Feb. 18 to 20, as Sinus Meridiani appears on the western limb. By the 24th, Sinus Meridiani is central, and in the remaining days of the month, Syrtis Major appears progressively more prominent on the western limb.

Night owls are in for a treat Feb. 5/6. The First Quarter Moon will pass in front of the stunning Pleiades star cluster (M45), hiding each star in turn for a period of an hour or so.

The entire event is observable from the western third of the continental U.S., with the Moon setting in the middle of the cluster from the eastern U.S. The event is also visible from countries with a similar longitude.

From Kansas City, Electra is occulted at 1:21 a.m. CST with the Moon 10° high in the west. Observers with a clear horizon may see Merope occulted at 1:57 a.m. CST, with the Moon just over 4° high. Those farther west see more occultations, including Alcyone and Atlas. Look for local timing on the International Occultation Timing Association’s webpage for bright star occultations (www.lunar-occultations.com/bobgraze/index.html), or check the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada’s 2025 Observer’s Handbook.

The Pleiades are occulted monthly in a series that began Sept. 5, 2023, and will continue until July 7, 2029. Some events are not visible from North America or occur in daylight.

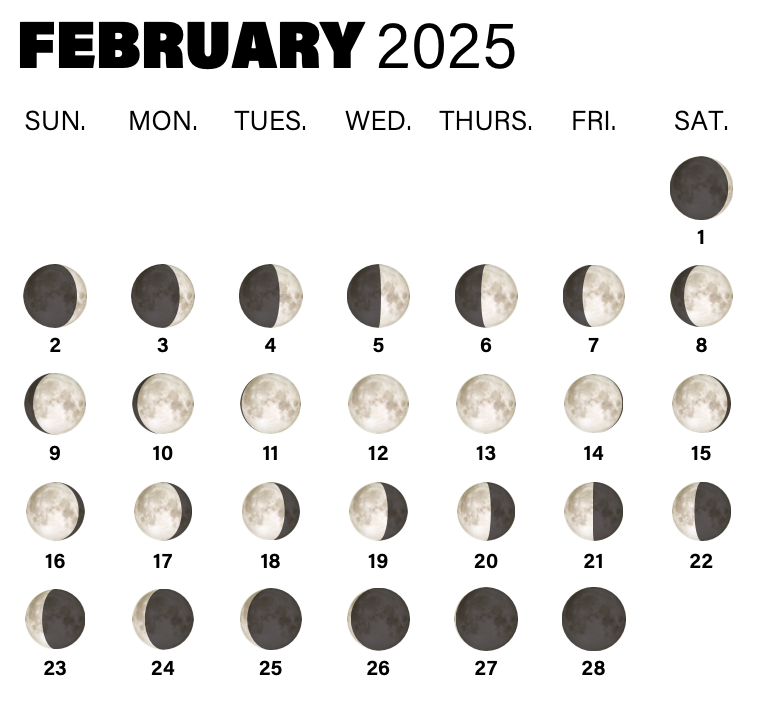

Rising Moon: A long-lasting crescent

Northern Hemisphere observers of the crescent Moon love spring. Skywatchers have unparalleled views of the thin crescent resplendent with earthshine, perched in a deep indigo sky painted with a horizon of fiery orange and red. Binoculars add a jaw-dropping experience. Selenophiles (or lunatics, as friends call us) are wowed by the large crater walls and peaks near the limb, which cast long shadows at this low Sun angle. The enjoyment is sweet and long-lasting because the Moon sits high in early twilight, thanks to the steep angle of the ecliptic.

Next month on the 2nd, the large craters Langrenus and Petavius are right on the terminator, just catching the first rays, but this month on the 2nd, the Sun has reached the peaks and western walls. Eighty-mile-wide Langrenus is not as young as Copernicus, but its features are still relatively sharp. A couple of nice central mountains stand out from the surrounding slumped walls. In a few nights you will see its apron of debris, secondary craters, and ejecta rays more easily.

Petavius to the south is a bit bigger, a bit older, and sports extra features. Its rim is softer, telling of a longer life of bombardment. Its most interesting feature is a huge radial fracture emanating from its complex cluster of peaks. Look closely and you should also be able to pick up a large, curving crack closer to the rim. Both of these fractures were created when lava from below heaved up the floor and later subsided. Junior bakers see these effects in their pie crusts if they have not learned to vent the steam.

The next transformation takes place on the 14th, just after Full phase, when sunset arrives and the light has switched sides. Over the course of a few hours, the shadows of the central peaks get longer and eventually touch the crater rims.

Meteor Watch: A quiet month

February has no major meteor showers. Sporadic meteors can be seen at any time, so it’s worth keeping watch for the occasional bright streak while observing the wonders of the night sky.

As we approach the vernal equinox, the zodiacal light makes an evening appearance on moonless nights. The most favorable time is the second half of the month, when the Moon is in the morning sky. Pick a dark location with a clear view west. Right after dusk, as the sky darkens, watch for a cone-shaped glow, similar to the Milky Way. Whereas twilight is a low, diminishing glow to the west, the zodiacal light is a steeply angled cone aligned with the ecliptic, extending up through Taurus. It lasts over an hour and is caused by sunlight reflecting off billions of meteoritic particles.

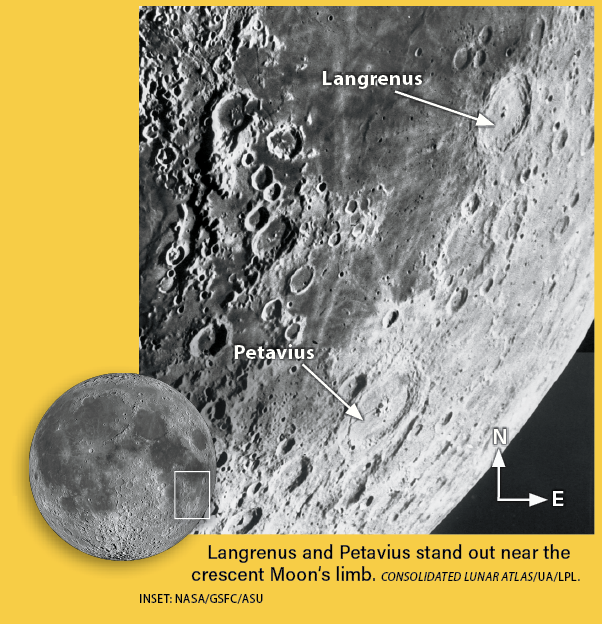

Comet Search: Drought may offer a surprise

An absence of bright comets leaves us hoping for an outburst from an unruly Centaur or the fresh delivery of an inbound primordial newbie.

Centaurs such as 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann orbit between Jupiter and Neptune, having migrated in from the Kuiper Belt. This enigmatic object erupts semi-regularly, causing a one-day jump in brightness from a feeble 15th magnitude to 10.5 — not tough for an 8-inch scope under dark skies and within range of an imager from the suburbs. Look for it south of Regulus this winter.

Calibrate your mind by starting on 9th-magnitude NGC 2903 in Leo’s Sickle; this spiral was a smidge too faint for Messier. Follow up with nearby NGC 2916 (magnitude 12.6); try powers of 150x or more. When you swing over to the comet’s position, you’ll have an outburst if it’s brighter than NGC 2916.

Sometimes a small comet comes out of the deep and approaches Earth closely enough to shine at 7th to 8th magnitude within six months of discovery. Check Astronomy.com for announcements and finder charts.

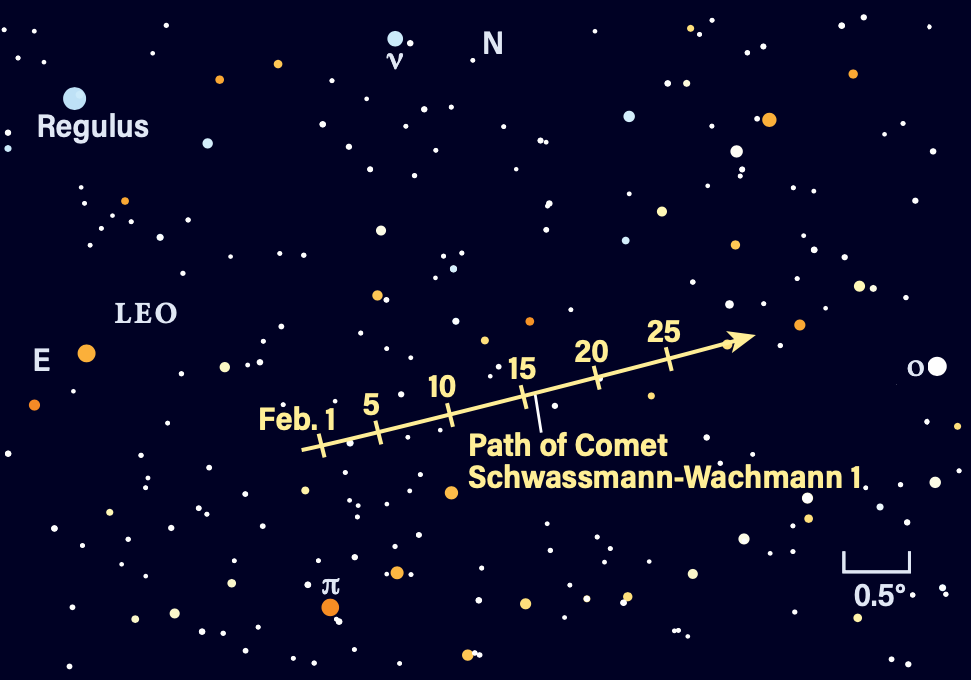

Locating Asteroids: Path through the stellar forest

Years ago, I was startled by the sudden disappearance of stars as I searched for cluster NGC 1746 in Taurus. Main-belt asteroid 15 Eunomia beckons me to return to the wonderful lanes of interstellar dust in this rich part of the winter Milky Way.

Suburban observers can start at magnitude 5.5 103 Tauri or 6th-magnitude NGC 1746. Slowly shift your scope 1° north and all the 7th- to 8th-magnitude field stars drop from sight. Magnitude 9.6 Eunomia becomes a standout.

Because the 170-mile-wide space rock is a slow mover, it is best to make a sketch of the field with four to six dots, then come back another night to identify the one that is missing. Eunomia passes good background patterns for this from Feb. 7–11, 20–21, and 27–28.

The ideal view is a 3°-wide field from a dark site, but sweeping a scope manually from Beta (β) Tau toward Aldebaran is an eye-opening experience. If E.E. Barnard had imaged this region, there would be many objects bearing his name, but Beverly Lynds picked up where he left off, gifting us plenty of Lynds Dark Nebulae (LDN) to “not see.”

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 35° north latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

10 p.m. February 1

9 p.m. February 15

8 p.m. February 28

Planets are shown at midmonth