The new year opens with a spectacular array of planets lined up in the western sky soon after sunset. Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn offer nightly fascination. A crescent Moon skips along this line of planets over a few nights early in the month. The inner pair of planets, Mercury and Venus, swaps places in the first week of January. Mercury remains in view through midmonth, while Jupiter and Saturn are visible all month. Uranus and Neptune can be spotted with binoculars, riding high in the southern sky after sunset. Only Mars is missing from the nightly lineup — it’s over in the morning sky, transiting the rich star clouds of the Milky Way.

Four major planets crowd the evening twilight sky in early January, strung like jewels on a necklace along the line of the ecliptic. Catch them Jan. 1, because Venus will dip out of view after the first few days of the month. It’s heading to a Jan. 8 inferior conjunction. On Jan. 1, Venus sets about 1 hour after the Sun. Look for it 5° high in the southwest 30 minutes after sunset, shining at magnitude –4.2. Nearby, just 8° to the upper left, is Mercury, glowing a fainter magnitude –0.7.

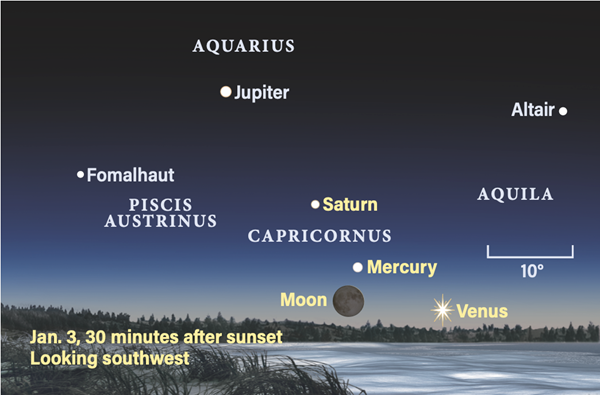

The pair of inner planets is joined by a 1-day-old, very slender (2 percent lit) crescent Moon Jan. 3, just 11.5° left of Venus. Look 12° above our satellite for the ringed planet Saturn (magnitude 0.7) in Capricornus. Higher still, in Aquarius, lies Jupiter, shining at magnitude –2.1. The four major planets span a total of nearly 40°.

Venus drops out of view soon after — how long can you keep track of it in the evening sky? It will reappear in the morning sky around midmonth, rising in the east about an hour before the Sun and shining at magnitude –4.3.

Venus’ visibility improves in a darker sky throughout the rest of the month, and it stands 12° high an hour before sunrise on Jan. 31. Through a telescope, Venus changes from a 1′-wide slender crescent that is 1 percent lit on Jan. 15 to a 50″-wide, 15-percent-lit disk on Jan. 31.

Meanwhile, Mercury is rising higher each evening, improving its visibility. It climbs toward Saturn and reaches greatest elongation east (19° from the Sun) Jan. 7, then shining at magnitude –0.5.

Saturn and Mercury appear closest on the evenings of Jan. 12 and 13, separated by 3.4°. Mercury has dipped in brightness to magnitude 0.4 by the 14th, and matches Saturn’s brilliance the next evening. The smaller planet fades further as it begins a brisk inward path to its Jan. 23 inferior conjunction. By Jan. 17, it has dimmed to magnitude 1.7 and become much harder to spot in bright twilight. Mercury sets within an hour of sunset.

Saturn falls in altitude each evening as well. On Jan. 4, catch the Moon and Saturn side by side, separated by about 5°. Saturn becomes lost in the solar glow a few days after Mercury and is no longer easily observable. It’s only 5° high 30 minutes after sunset on Jan. 20 and, at magnitude 0.7, it’s easily lost in twilight.

Jupiter maintains its visibility throughout the month. It’s a fine object in late twilight in the first week of January and is the brightest of the evening planets after Venus leaves the scene. On Jan. 1, Jupiter stands roughly 30° high in the southwest an hour after sunset. On Jan. 5, Jupiter is 5° north of the crescent Moon, now just over 3 days old.

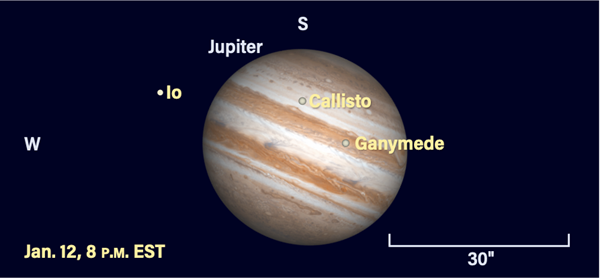

Jupiter’s disk spans 35″ and easily shows off its dusky orange pair of dark equatorial belts in any telescope. The four Galilean moons are on ready display — catch them this month before Jupiter leaves the evening sky in mid-February. It’s your last chance before solar conjunction to watch the changing configuration of the four moons.

Although the observing window for seeing satellite transits is narrow, don’t miss the Jan. 5 transit of Ganymede’s large shadow — the event’s long duration (3.5 hours) means most observers across the U.S. will see part of the transit as darkness falls, although you’ll need to catch it early if you’re in the Pacific time zone. It begins at 6:20 P.M. EST and ends at 9:50 P.M. EST — that’s 6:50 P.M. PST for those in the western U.S. As its shadow creeps across Jupiter’s face, Ganymede itself stands west of the planet.

Another event not to miss is the Jan. 12 dual transit of Ganymede and Callisto across Jupiter. It’s quite rare to catch these two moons transiting together. Callisto’s transit begins at 5:22 P.M. EST, followed by Ganymede at 6:50 P.M. EST. Watch as long as you can to see Ganymede catching up with Callisto — the latter’s smaller orbit results in faster movement across Jupiter’s face. Also don’t miss Io creeping up on the western limb of the planet, disappearing behind Jupiter at 8:36 P.M. EST, an event visible from the western half of the country. In the Pacific time zone, Callisto’s transit ends at 6:45 P.M. PST and Ganymede exits the disk at 7:24 P.M. PST.

By Jan. 31, Jupiter stands only 11° high an hour after sunset; such a low altitude makes viewing any planetary details very difficult.

Neptune is a binocular object shining at magnitude 7.8 and located in Aquarius the Water-bearer. It stands halfway up in the southwestern sky Jan. 1 as soon as it’s dark. Since Neptune sets mid-evening, try to catch it early. Binoculars are a good first step to finding the planet. Try on Jan. 6, when the crescent moon stands 12° east of Jupiter and Neptune stands 8° northeast of the Moon.

Neptune lies 3.3° northeast of the 4th-magnitude star Phi (ϕ) Aquarii, an easy guide star with two 6th-magnitude stars to its northeast. Neptune moves east along the ecliptic and by Jan. 31, it stands 4° northeast of Phi Aquarii and lies very close (5′) to a 6th-magnitude field star. At a huge distance of 2.9 billion miles from Earth, its disk spans only 2″ through a telescope. Use high magnification on a steady night of seeing in order to see its bluish-green disk.

Uranus lies about 60° high in the southeastern sky soon after sunset and remains visible until the early morning. It’s a binocular object among the stars of Aries the Ram, shining at magnitude 5.8 in a sparse region of the sky. It is about 11° southeast of Hamal, the brightest star in Aries, and 5.3° northwest of Mu (μ) Ceti. Uranus moves westward during the first half of the month, reaches a stationary point Jan. 18, and resumes an easterly trek for the remainder of the month. Uranus spans nearly 4″ in a telescope and sports a distinctive greenish-blue hue. This distant ice giant lies 1.8 billion miles away.

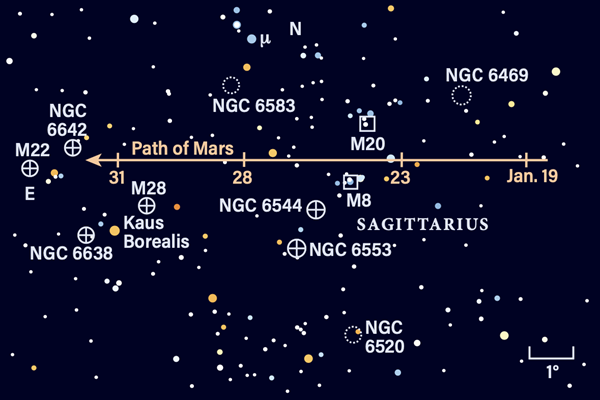

While six planets congregate in the evening sky in early January, you have to wait until the predawn hours to catch Mars. The Red Planet rises before 6 A.M. local time all month and brightens marginally from magnitude 1.5 to 1.4 during January. Mars is crossing a stunning region of the sky and is worth watching through low-power, wide-field telescopes as it glides past numerous nebulae. It’s a challenging object through a telescope, spanning only 4″.

Mars lies in Ophiuchus as the new year opens, standing less than 6° northeast of Antares. It crosses into Sagittarius by Jan. 19, about 4° west of the Trifid (M20) and Lagoon (M8) nebulae. The morning of Jan. 25, Mars stands less than 1° south of the Trifid and roughly half a degree away from the Lagoon. On Jan. 26, Mars is less than a Moon’s width from the northeastern edge of the Lagoon Nebula — a fine sight through binoculars.

Don’t miss the amazing waning crescent Moon on Jan. 29, standing 3° south of Mars an hour before sunrise. They’re joined by Venus, only 10.5° to Mars’ northeast. Check out these two planets in the midst of the Milky Way. Our galaxy’s plane lies at a fairly shallow angle with respect to the southeastern horizon, but observers with suitably clear skies will have fine opportunities for scanning the region with binoculars or capturing some spectacular wide-field photos. The Red Planet ends the month 1.3° northwest of M28, a dim globular cluster (magnitude 6.8), while a brighter (magnitude 5.1) globular cluster, M22, lies 3.5° due east of Mars.

Rising Moon: Ports in a storm

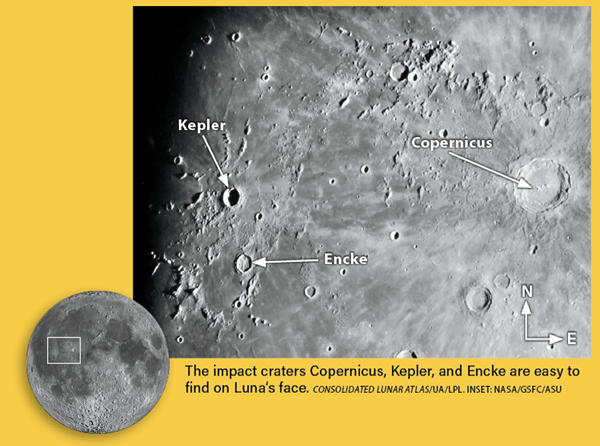

There’s no hiding the crater Kepler! The youthful impact scar stands out on the Moon’s equator, a veritable island in Oceanus Procellarum, the large basin on the eastern flank of our satellite. Kepler is a smaller version of the prominent Copernicus, which lies closer to the Moon’s center.

Kepler is a round, sharply defined deep bowl. On the 13th, the low Sun angle highlights the rough skirt of debris that spread out during the impact event that created it. A bit to the south lies Encke, similar in size to Kepler, but its older, bombarded rims are softer and, more importantly, it is filled with Kepler’s rubble.

Return in the next couple of evenings to see how a higher Sun angle transforms the roughness and shadows into a bright apron with rays. The lava of Procellarum is thinner here, which permitted the impact to gouge out lighter-hued rock from below. To the south, Encke has all but disappeared. Typically, the older the crater, the less it is visible under a high Sun.

Meteor Watch: A fine New Year’s show

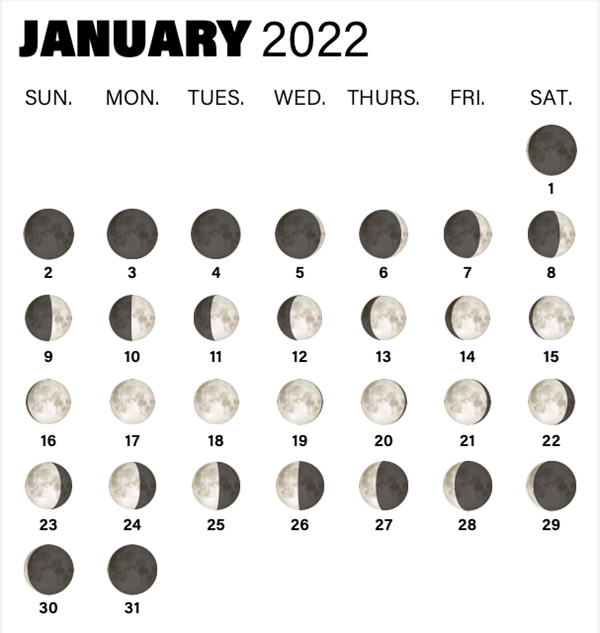

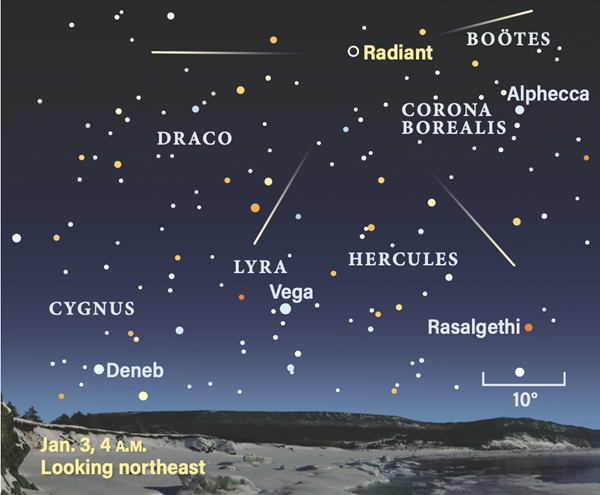

The Quadrantids, which originate in what is now the northern region of Boötes, are active between Dec. 28 and Jan. 12. The narrow peak of activity (six hours, according to the International Meteor Organization) occurs Jan. 3. With the Moon near New, if the weather cooperates, the chances are good for a fine view. The predawn hours are always the best time to view meteor showers, and the Quadrantids are no exception. The radiant rises late in the evening and by 4 A.M. local time, it’s about 40° high. Expect about 25 to 30 meteors per hour if the peak occurs during the dark window of your observing site, corresponding to a zenithal hourly rate of 100 to 120. Look also for the occasional fireball known to occur with this shower.

The Quadrantids’ parent object, 2003 EH1, was discovered in 2003 by Brian Skiff at Lowell Observatory. The former comet nucleus now carries a typical asteroid designation and its orbital parameters closely match those of Quadrantid meteors.

Comet Search: Bowling across the stars

Comet C/2021 A1 (Leonard) claimed the title of comet of the year in 2021, but it plummets to 12th magnitude by January’s end.

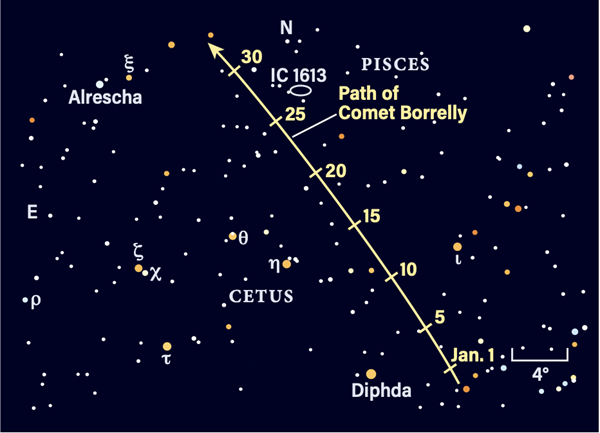

Next up: Nicely placed on the evening stage well to the left of Jupiter is the periodic Comet 19P/Borrelly, floating near Diphda, the 2nd-magnitude nose star of Cetus. Though it’s not a contender for this year’s title, Borrelly should sport a broad, short fan extending to the south. Even from darker country skies, a 4-inch scope won’t show much more than an out-of-round pale gray cotton ball glowing at 10th magnitude. Try magnifications above 100x with a 6-inch to note the well-defined northern flank.

During the bright Moon period from the 5th to the 21st, the geometry barely changes, but a surprise flare-up can never be ruled out. Its close approach to the Sun on Feb. 1 is closer to Mars’ orbit than Earth’s.

Discovered from France by Alphonse Borrelly in 1904, this comet was the third to be visited by a spacecraft. In 2001, Deep Space 1 unveiled its 5-mile-long bowling pin shape, similar in size to Halley’s Comet. Jupiter tugs on Borrelly every 12 years or so, morphing its orbit with each apparition and wreaking havoc on its arrival times into the inner solar system.

By midnight, the 10th- to 11th-magnitude Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko has risen in the east not far from M44, the Beehive star cluster.

Locating Asteroids: Ceres serenades the Bull

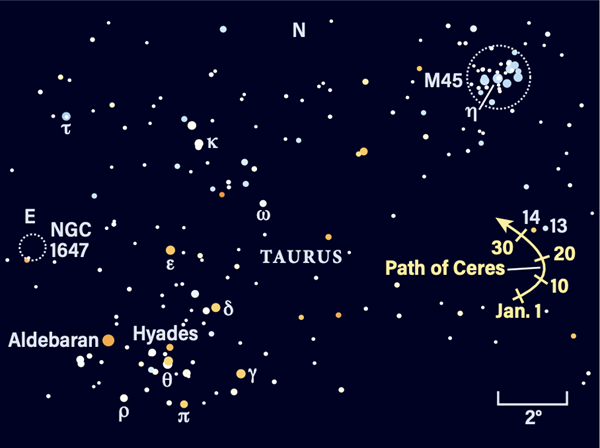

The famous dust clouds surrounding the Pleiades (M45) spread far and wide. They hide many distant stars, helping us locate and track dwarf planet 1 Ceres this month.

The 600-mile-wide interplanetary rock has fallen behind Earth and is slowly fading from magnitude 7.8 to 8.3. This is pretty easy for the smallest telescope from the suburbs, but binocular users will have a tougher time picking out the faint dot.

If you place the Pleiades on the northern edge of your binocular field, to their south you’ll see a slightly unequal pair of 6th-magnitude stars: 13 and 14 Tauri. Ceres will be the next brightest dot south of these. It’s a slow mover, so it might take a couple of nights to notice the shift against the widely separated anchor stars. Give the search a rest from the 12th to the 14th, as the Moon swells toward Full phase between the Pleiades and Aldebaran.

A treat for small scope users is the five-night passage of 44 Nysa across the Moon-sized sparse star cluster NGC 1647 from Jan. 28 to Feb. 3. You can get there by picturing flipping the Hyades to the other side (northeast) of Aldebaran. At 10th magnitude, Nysa is a perfect clone of several of NGC 1647’s cluster members, but within three hours you can pick up its movement relative to the background.