Early winter sunsets offer nice evening views of the planets, starting with Mercury and Venus. Mercury quickly drops away, only to reappear in the morning sky before the end of the month. Venus is dazzling in the west and later in the month has a close encounter with Saturn, a stunning sight in small telescopes. Mars and Jupiter dominate the evening sky and the Red Planet is occulted by the Moon for observers in the southern U.S. Uranus and Neptune wander among fainter stars but are easy targets for binoculars or small scopes.

Let’s begin on the evening of Jan. 1. Mercury is the first planet to set, within an hour of the Sun. Look with binoculars 6° due west of Venus 20 minutes after sunset for magnitude 1.1 Mercury to pop into view. At 6° high, you have about 30 minutes before it drops too low. By Jan. 3, Mercury fades to magnitude 2.2 and is very difficult to spot. It passes through inferior conjunction on the 7th, then reappears quickly in the morning sky; we will return to it later.

Venus stands 9° high in the southwest 20 minutes after sunset on Jan. 1. It dazzles in azure twilight at magnitude –3.9. The planet’s angular elongation from the Sun increases from 17° to 24° during the month — a long, slow climb until it reaches greatest elongation in June.

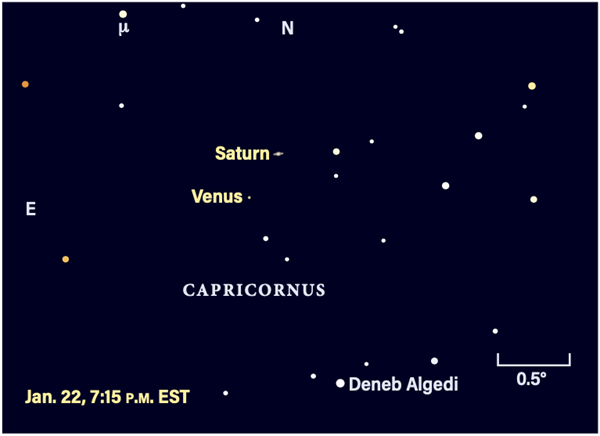

Venus spends most of the month in Capricornus and slides along the ecliptic to meet Saturn Jan. 22, when the two are separated by only 21′. Check them out together in the same field of view in your telescope. A one-day-old Moon hangs 8° below them; spy this lovely view within half an hour of sunset, against the darkening sky. Venus and Saturn set nearly two hours after the Sun. The next day, a fatter crescent Moon is less than 7.5° east of Venus.

Venus crosses into Aquarius on the 24th. Through a telescope, it changes very slightly this month, growing from 10″ to 11″ across. Its gibbous phase slims from 96 percent to 91 percent lit between Jan. 1 and 31.

Saturn descends quickly into the twilight of January evenings. Its low altitude affects telescopic views. Catch it in the first week of January, when it is more than 20° high in the southwest shortly after sunset, glowing at magnitude 0.8. The rings in twilight are a wonderful sight and you have about an hour to observe them before the altitude really begins to affect the view. By mid-January, Saturn is less than 15° high an hour after sunset and likely resembles jelly pudding more than a ringed planet, but its conjunction with Venus is a must-see. By Jan. 31, Saturn is 14° east of the Sun and is quickly lost after sunset. It reaches conjunction with the Sun next month.

Neptune is a relatively easy binocular object high in the southwest once the sky is dark. Located in eastern Aquarius, the dim, distant planet shines at magnitude 7.8 in a region devoid of bright stars. Instead, Jupiter 8° to its east is a useful guide.

In the first week of January, Neptune is located between two 7th-magnitude stars. If you’ve been following the planet, you know them. Find the easternmost pair of a parallelogram of four stars each about 1° apart, 5° northeast of Phi (ϕ) Aquarii. Neptune lies close to the northernmost star, passing 6′ due south of it Jan. 11. By Jan. 20, Neptune sits 12′ due east of the same star. The gap more than doubles by the end of January. A crescent Moon floats within 4° of Phi on Jan. 24, with Neptune some 5° above the Moon.

Attempt telescopic views early in the month and soon after dark, when the planet is over 30° high. The tiny disk spans 2″, hard to observe unless conditions are ideal. Lower altitudes really affect its clarity.

Jupiter shines brightly in the southwest these winter evenings. It starts the month at magnitude –2.4 and slips by only 0.2 magnitude by Jan. 31. It treks eastward across the faint stars of Pisces the Fish. Watch for the lovely four-day-old crescent Moon to arrive Jan. 25, when the pair stand 3° apart.

Jupiter’s disk spans 39″ on Jan. 1 and shrinks by about 8 percent by Jan. 31. Start your observing in late twilight, when Jupiter’s brilliance is tempered by the background sky. The two dark equatorial belts straddling the equator first come into view, with more subtle features following with patient observing.

Io undergoes an occultation the evening of Jan. 1, opening a month of fine events. The moon disappears behind the western limb of Jupiter around 7:45 P.M. EST. The following evening at the same time, Io has made half an orbit and its shadow is in the middle of transiting Jupiter’s face. The shadow leaves just before 8:40 P.M. EST.

West Coast observers can see Callisto partially occulted by Jupiter’s northern limb Jan. 7, beginning around 8:30 P.M. PST and lasting nearly an hour. The event repeats Jan. 24, this time for the eastern half of the U.S., starting around 7:10 P.M. EST.

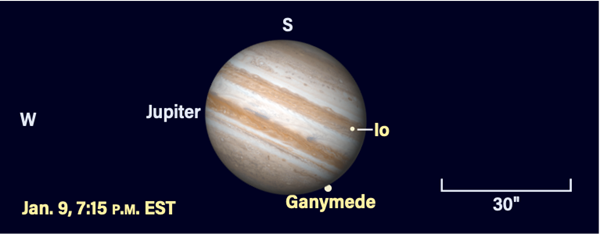

Two events occur Jan. 9, when Io starts a transit around 7:05 P.M. EST. Ganymede slips out from behind Jupiter shortly after, around 7:09 P.M. EST. The giant moon takes about five minutes to fully reappear.

Europa begins a transit on Jan. 19 at about 7:45 P.M. EST. Its shadow doesn’t appear until just after 10:10 P.M. EST, less than 10 minutes before Europa itself leaves the opposite side of the disk. The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada’s 2023 Observer’s Handbook lists other events throughout the month.

Uranus lies in sparse southern Aries, an easy binocular target at magnitude 5.7. Look for a pair of 5th-magnitude stars, Sigma (σ) and Pi (≠) Arietis, creating a 2.5°-long north-south line. Uranus is a little less than midway between these stars on Jan. 1, a bit closer to Sigma. The planet drifts slightly west of a line joining the stars throughout January. Uranus gradually slows to a stationary point Jan. 22, 1° northwest of Sigma Arietis.

The planet is visible all evening and sets soon after 1 A.M. local time by January’s end. Through a telescope, its 4″-wide disk appears blue. On Jan. 28/29, look for Uranus close to the gibbous Moon in the late evening. Uranus stands only 0.5° due south of the Moon’s southern limb soon after midnight on the 29th for East Coast observers (still the 28th in all other U.S. time zones). Earlier in the evening, Uranus is southeast of Luna’s southern limb.

Mars is a spectacular object in Taurus, shining at magnitude –1.2 on Jan. 1. That night, the Red Planet is nearly 70° high around 8:30 P.M. local time. Mars lies about 9° east of the Pleiades star cluster (M45) and 8.5° north-northwest of Aldebaran. The planet slows to a halt Jan. 12, ending its retrograde motion and resuming an easterly trek, reaching 10° east of M45 by Jan. 31, when Mars sets just before 3:30 A.M.

Watch Mars and the waxing gibbous Moon close in on each other Jan. 30. For northern states, the two lie very close, just a few arcminutes between them. From locations south of about 37° north latitude, the Moon occults Mars; the time depends on your location. From Miami, Mars is occulted at 12:38 A.M. EST on Jan. 31 and reappears at 1:27 A.M. EST. In Dallas, Mars disappears at 11:18 P.M. CST on Jan. 30 and reappears nearly four minutes after local midnight on the 31st. Los Angeles observers see Mars vanish at 8:36 P.M. PST and reappear at 9:29 P.M. PST. Mars takes nearly a minute to disappear and reappear, so prepare your scope 30 minutes before the event and begin observing at least five minutes before the occultation is set to start.

Through a telescope, Mars is well past its best. On Jan. 1, it spans 15″ and is 97 percent lit, large enough for moderate telescopes to see surface features. By the end of January, it shrinks to 11″ wide and surface features become more challenging. The phase slims to 92 percent. Mars also fades to magnitude –0.3.

At about 9 P.M. Central time, the following features are visible (for the mid-U.S.): Jan. 1: Sinus Meridiani with Syrtis Major leaving the disk; Jan. 10: Syrtis Major, Hellas, and Elysium; Jan. 23: Olympus Mons, Tharsis Ridge, and Mare Sirenum; Jan. 30: Tharsis, Valles Marineris, Solis Lacus, and Mare Erythraeum. Features and their positions vary depending on the time and your location.

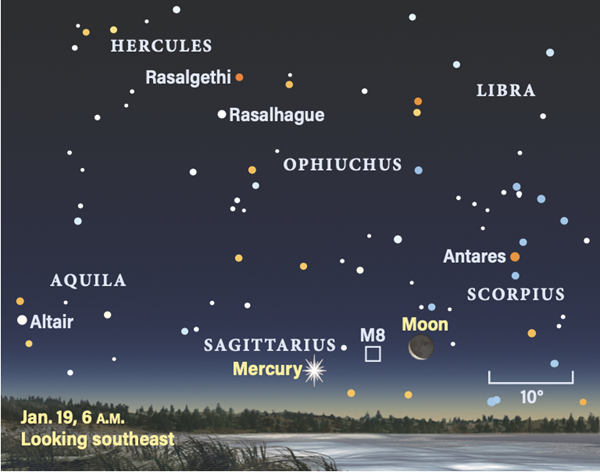

Mercury skips into the morning sky after its Jan. 7 inferior conjunction and quickly attains visibility by mid-month. It reaches magnitude 0.6 on the morning of Jan. 17 and stands 5° high in the southeast 45 minutes before sunrise.

Look for Mercury nearly 15° left (east) of the waning crescent Moon on Jan. 19. The magnitude 0.4 planet is only 1° high at 6:00 A.M. local time; the Moon is four times higher, so use it to spot the innermost planet. You’ll need a clear southeastern horizon. The Lagoon Nebula (M8) lies roughly midway between the two; binoculars should net it before the sky brightens too much.

By Jan. 25, Mercury reaches magnitude 0 and stands 8.5° high in eastern Sagittarius around 6:45 A.M. local time. On Jan. 30, it glows at magnitude –0.1 some 7′ northeast of 4th-magnitude Omicron (ο) Sagittarii. This is Mercury’s greatest elongation west, 25° from the Sun. On the 31st, Mercury stands 40.5′ due south of Pi Sagittarii and is 4° high a full hour before sunrise.

Earth reaches perihelion, the closest point to the Sun in its orbit, Jan. 4 at 11:17 A.M. EST, when we stand 91,402,515 miles from our star.

Rising Moon: Good librations

Have you ever watched someone roll their head to stretch their neck? You don’t see the back of their head, but you can view more than just their face. Our sister Luna performs a similar maneuver, called libration, with a 27-day period, revealing a total of 9 percent more than just her face to us: We also get a peek at the top, bottom, and sides. Binoculars are the best way to follow this motion, yet it is noticeable even to the discerning eye. We’ve hit the timing just right this month, as the 29.5-day illumination cycle is in sync with the roll.

January opens with the east (right) edge prominently displayed, with Mare Crisium as far as it can get from the limb. As we approach Full Moon, the north seems to roll away, while down south, the pure white of the lunar highlands begins to blotch. The dense jumble of craters takes on gray, their bowls containing patches of lava that together make up Mare Australe. Notice how far up Tycho appears — six months from now, it will lie much closer to the southern limb. And check out the west, where the large gray oval of Grimaldi sits a bit more than once its own width from the edge, while the huge Oceanus Procellarum extends right to the limb.

Post Full phase, switch over to morning viewing (even past sunrise) to follow the libration with just a pair of binoculars. Grimaldi rolls away from the limb and each passing day reveals more and more of the white coastline of Procellarum in the northwest.

The next cycle opens with the waxing evening crescent on the 24th. Find the large patch of Mare Humboldtianum in the northeast; to its southwest lies the lovely oval-shaped Endymion. The striking pair Atlas and Hercules are further inward still. Mare Crisium is a fair distance in, letting the dark patches of Mare Smythii and Marginis highlight the limb. The whole sequence now nearly repeats, starting two days earlier.

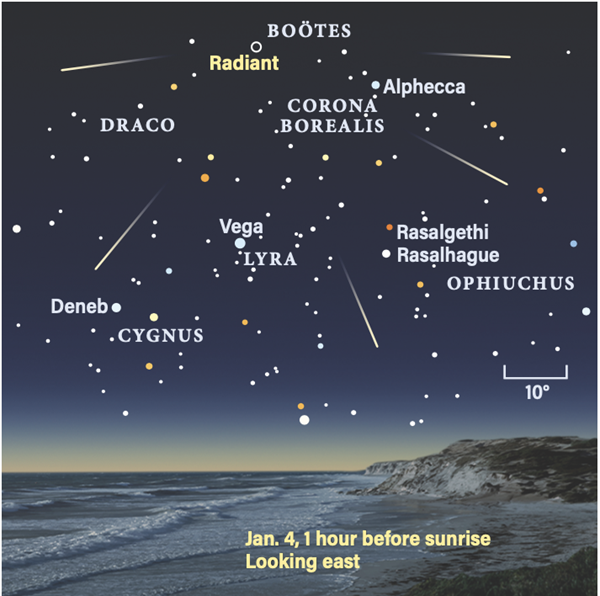

Meteor Watch: Catch a few falling stars

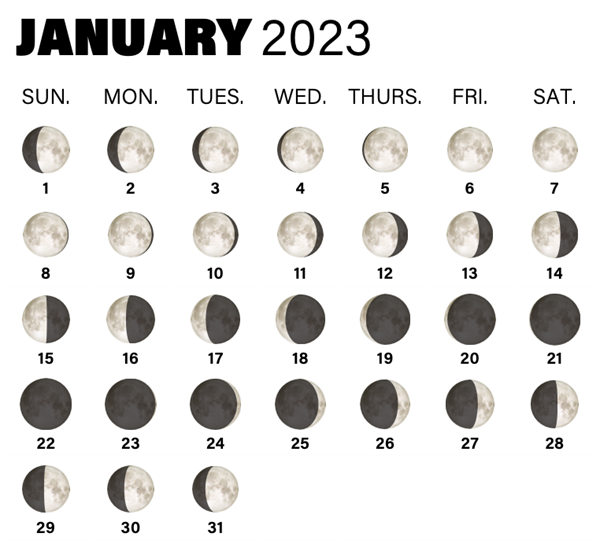

This annual winter shower is a regular for observers, but early January’s Full Moon strongly affects viewing this year. The Quadrantids, named after a defunct constellation in what is now northern Boötes, are active from Dec. 28 to Jan. 12, peaking late on Jan. 3 in the U.S. Full Moon occurs on the 6th. Only brighter members of the shower, which normally generates about 40 meteors per hour before dawn, will be visible. Though this year’s predicted zenithal hourly rate is 110, with the Moon around, you’ll see far fewer.

The radiant rises after midnight, offering a steady increase in rate as dawn approaches. Brace against those cold winter temperatures as you enjoy your morning cuppa outside and gaze upward. You might catch one of the rare bright ones. The Quadrantids are associated with the periodic comet 96P/Machholz and the minor planet 2003 EH1.

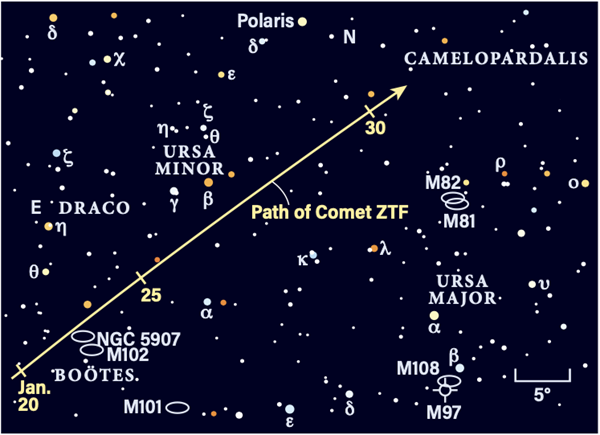

Comet Search: Sky trip!

Let’s get the most from the bright binocular comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF) during its speedy two-month flight. Barring a welcome surprise, ZTF will be the best of the year. South of the equator, observers instead get 12 months of the stalwart C/2017 K2 (PanSTARRS) skirting their pole.

ZTF brightens rapidly from 9th magnitude into binocular range while accelerating toward perihelion on the 12th. Despite the Full Moon mid-month, try to catch the 6th-magnitude fuzzball from the suburbs. By the 18th, early risers can enjoy ZTF high in the northeast without interference from the waning crescent Moon. Those preferring to stay up until 2 A.M. can observe before the Moon rises two nights earlier, but know the comet might be fighting trees and buildings.

Imagers on the morning of the 22nd will enjoy ZTF’s green glow with M102 and the Splinter Galaxy (NGC 5907) only 3° away. Visual observers, watch the wedge-shaped tail suddenly narrow into a spike on the 24th, then quickly spread back out in only 48 hours as Earth punches through ZTF’s orbital plane at nearly a right angle. Geometry favors us with a short sunward-pointing anti-tail, which could be blue if ZTF produces enough gas. This climax might last only one night, so be prepared to jump into action.

ZTF is closest to Earth at month’s end, potentially glowing as bright as 5th magnitude not far from Polaris. Its rapid motion of 12″ per minute forces short exposures to keep details sharp. Dedicated astroimagers could make a two-week panoramic composite.

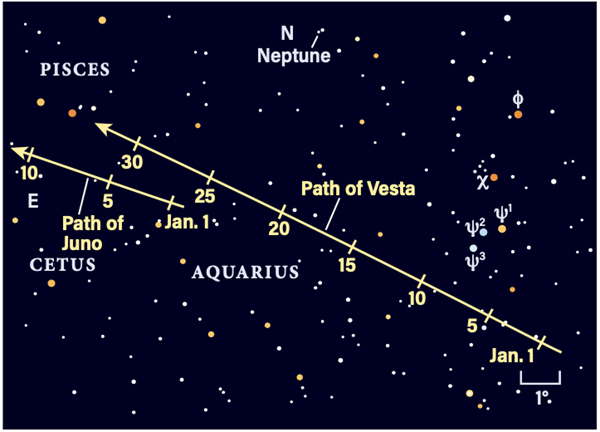

Locating Asteroids: Vesta swims past Neptune

Much easier to find than last month, asteroid 4 Vesta passes the standout broad triplet of ψ1, ψ2, and ψ3 Aquarii. The Greek letter psi (ψ) looks nearly the same as Neptune’s planetary symbol because in Greek, the god’s name is Poseidon. And, by coincidence, the blue ice giant is only some 5° north of Vesta’s path.

We’re a fair distance from the plane of the Milky Way here, so the background star fields contain a varied smattering that is straightforward to navigate. In just an hour at the eyepiece on the 4th, you can watch Vesta separate from a pair of stars straddling its path. Consider also tracking down nearby 3 Juno, which leaves the scene early on. And avoid Jan. 25, when the Moon is nearby.

In yet another appulse, Uranus hosts 10th-magnitude 27 Euterpe 1° to its south during the first week of January. A box of stars acts as a great reference to reveal the night-to-night shift of that asteroid.