All the major planets are on view this month. Venus has a fine evening conjunction with Saturn and Jupiter is high in Taurus. Uranus and Neptune are binocular targets, while Mars reaches opposition. Early morning reveals Mercury. Additionally, on the 9th the Moon crosses the Pleiades (M45), and on the 13th it hides Mars in a rare event.

Venus dazzles in the southwestern sky after sunset all month. Starting at magnitude –4.4 and brightening quickly, it’s easily visible as twilight descends. On the 1st, Venus shows a 55-percent-lit disk spanning 22″. On Jan. 2 and 3, the waxing crescent Moon joins in, standing 10° southwest and 4° east of the planet, respectively. Notice on the 4th that the Moon is 4° northeast of Saturn, which is about 13° from Venus.

Venus reaches greatest eastern elongation Jan. 9, 47° from the Sun and setting almost four hours after sunset.

The moment Venus shows a 50-percent-lit disk is called dichotomy. The exact moment can vary from predictions by up to four days. Check on Jan. 11, the predicted date of dichotomy. What do you observe?

Venus closes the gap to Saturn over the next few days, standing just under 4° west of the gas giant on the 14th and coming closest on the 17th, when only 2.2° separates them. By the 19th, Venus is 2.5° due north of the ringed planet, which shines at magnitude 1.1.

Venus crosses into western Pisces on the 23rd and ends the month 1.5° from Lambda (λ) Piscium. Its disk is now 32″ across and 38 percent lit.

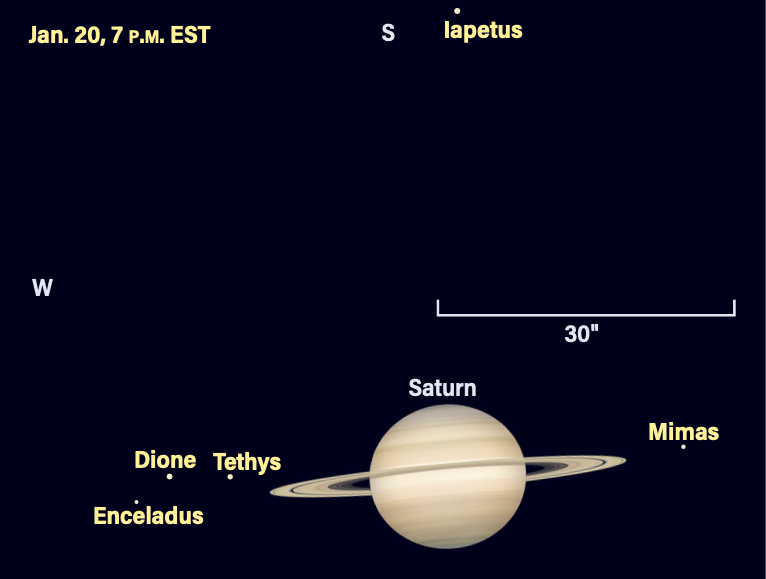

The best telescopic views of Saturn are almost gone, but you have a short period after evening darkness falls. Saturn is 30° high two hours after sunset on the 1st; it sets around 10 p.m. local time on the 1st and 8 p.m. on the 31st. It shines at magnitude 1.1 most of the month and lies south of Phi (ϕ) Aquarii.

Through a telescope, Saturn’s disk spans 16″. The rings are widest for the year in the first week of the month at 4°, and narrow to 3° by the 31st. They’re edge-on in March.

Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, is an easy target for any scope. It stands near the planet Jan. 6, 7, 14, 15, 22, 23, 30, and 31.

Iapetus is at its brightest western elongation, 8′ west of Saturn, on New Year’s Eve. During the first three weeks of January, it moves toward superior conjunction and fades from 10th to 11th magnitude. On Jan. 20, it lies only 47″ due south of Saturn, a great time to spot this enigmatic moon.

Neptune sits about 12° east of Saturn. Shining at magnitude 7.8, it can be spotted in binoculars. At the end of January it lies in the same binocular field as Venus, which acts as a marker to find the distant planet.

Early in January, Neptune forms a nice triangle with 20 and 24 Psc, which shine at magnitude 5.5 and 5.9, respectively. As January progresses, Neptune moves eastward, standing 1° due north of 24 Psc on the 29th. Venus is 3.5° from Neptune and remains a similar distance through the 31st.

Uranus appears fixed against the background stars of Aries as it ends its retrograde loop at the end of January. At magnitude 5.7, it’s an easy binocular target. Located about 8° southwest of the Pleiades, Uranus is south of a collection of 5th-magnitude stars, the brightest of which is 63 Arietis. Uranus stands 2.5° due south of this star.

It’s a great time to find Uranus in a telescope, higher than 60° after 8 p.m. local time. Its 4″-wide disk is a challenge, but try under good conditions with high magnification. It is visible until well after midnight all month.

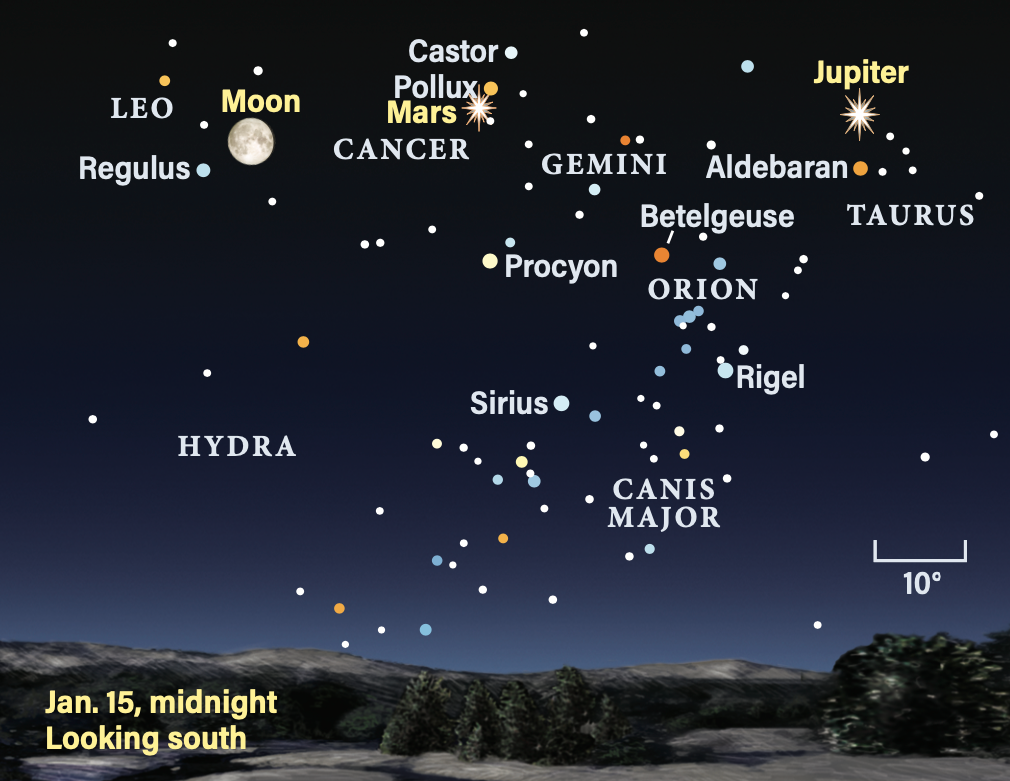

Dominating Taurus is Jupiter, altering the well-known constellation’s appearance. Jupiter spends most of January at magnitude –2.7. As soon as darkness falls, it is nearly 40° high in the east, a great time to observe with a telescope. It reaches its highest elevation just before 10 p.m. local time in early January, and two hours earlier at the end of the month.

The planet is 5.5° from a waxing gibbous Moon Jan. 10, and stands 5° north and slightly east of Aldebaran Jan. 31. Jupiter’s disk spans 47″ on Jan. 1 but drops to 43″ by month’s end. It offers a wealth of detail even in small scopes. Most days all four Galilean moons — Io,

Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto — are visible; at times one is hidden behind or transiting in front of the disk, along with its shadow.

Jan. 1 sees Io disappear and then re-emerge from Jupiter’s vast shadow. The moon vanishes behind the northwestern limb just before 8 p.m. EST. Watch the space 12″ east of the planet to see Io appear just before 10:45 p.m. EST.

Around 8:25 p.m. EST on the 6th, Europa begins a transit. Shortly before 10 p.m. EST, its shadow appears. Europa exits the disk at 11 p.m. EST; the shadow exits about an hour and a half later.

On the 16th, Io transits from 8:36 p.m. to 10:48 p.m. EST, with its shadow visible from 9:32 p.m. to 11:44 p.m. EST. As the shadow is exiting the western limb, Ganymede is occulted on the same side almost simultaneously, taking a few minutes to disappear.

Ganymede reappears at the northeastern limb around 1:51 a.m. EST (Jan. 17 in the Eastern and Central time zones). It then drops into Jupiter’s shadow 90 minutes later. You’ll see it starting to fade just before 3:30 a.m. EST.

Ganymede crosses the disk Jan. 27. East Coast viewers may catch the beginning of the transit at sunset. The moon exits starting around 7:20 p.m. EST. The shadow starts transiting around 9:40 p.m. EST, taking several minutes to fully appear and easily visible in small telescopes. The shadow transit ends beginning at 11:49 p.m. EST.

The highlight of the month is the opposition of Mars late on Jan. 15. It peaks at magnitude –1.4, as bright as Sirius. Mars starts January in Cancer and wanders west, entering Gemini by the 12th. This places it high in the sky around local midnight.

Oppositions of Mars occur every 780 days. The planet’s diameter reaches nearly 15″. Mars’ closest approach to Earth occurs Jan. 12, a few days before opposition. It then stands 59,703,891 miles away. (This is an aphelic opposition, not as close as a perihelic one.)

Mars will appear tiny in scopes smaller than 8 inches. Larger scopes provide better views. Be patient and watch for moments when Mars reveals its glory. Do you see the North Polar Hood or the brilliant white polar cap? The former should dissipate this season.

Mars appears to rotate backward when viewed at the same time each night. At 9 p.m. local time from the central U.S. (look an hour later in the east, and an hour or two earlier farther west), you’ll see Olympus Mons and the Tharsis Ridge region facing us in the first week of January. By Jan. 7, Valles Marineris is well positioned, followed a few days later by Solis Lacus. By mid-January, Sinus Meridiani dominates, then Syrtis Major after the 19th, with the bright Hellas basin to its south. During the last few days of the month, Mars shows off Mare Cimmerium.

On the 13th, Mars is occulted by the Moon. Timing depends on location, but the East Coast sees Mars disappear around 9 p.m. EST; this is soon after twilight fades in the Mountain time zone. It takes about 20 seconds for Mars to be fully covered. Along the Pacific Coast, this occurs soon after moonrise in evening twilight. Mars reappears about an hour later.

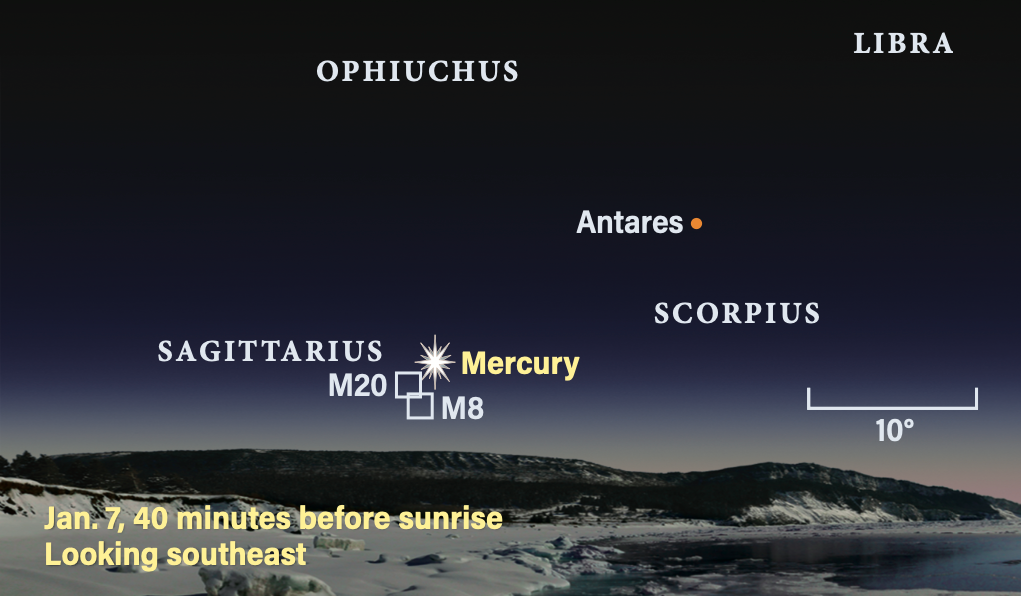

Mercury is visible in the early-morning sky. On Jan. 1 it is an easy object in twilight at magnitude –0.4, 12° east of Antares. It stands 6° high in the southeastern sky by 6:30 a.m. local time.

A week later, you’ll need to wait another 15 minutes for it to reach the same altitude. Check the region with binoculars because soon after Mercury rises, you might spot the Trifid (M20) and Lagoon (M8) nebulae 2° east and southeast of the planet, respectively — at least, you might see the stars embedded within them.

There’s a lot of uncertainty at the time of writing for the visibility of Comet C/2024 G3 (ATLAS), but it is 5° southeast of Mercury on the same morning (the 7th). Keep watch in case the comet exceeds expectations.

Mercury is less than 1° north of the Lagoon Nebula on Jan. 9, and by the 14th is within 15′ of M22, though the 5th-magnitude globular is invisible in twilight.

Mercury attains magnitude –0.5 by the 16th, but its elongation from the Sun has dropped. The planet is lost in twilight over the next few days.

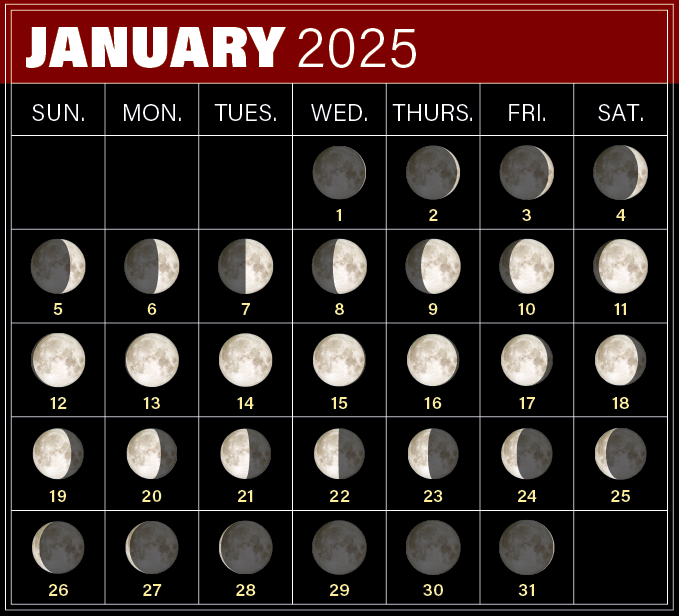

The Moon occults some stars in the Pleiades early on the evening of Jan. 9. The event takes place in darkness on the East Coast and begins in twilight farther west, occurring in daylight for the Pacific time zone.

The 10-day-old Moon tracks across the southern part of the cluster; the first star to disappear from some eastern locations is Electra, around 7 p.m. EST. Just over 20 minutes later goes 4th-magnitude Merope.

From Kansas City, Merope disappears about 6 p.m. CST, but the Moon misses Electra. About 35 minutes later from this location, the Moon reaches Alcyone. Atlas and Pleione are occulted approximately 45 minutes later. The timing is highly dependent on your location; check the International Occultation Timing Association’s website (www.lunar-occultations.com) or the 2025 Royal Astronomical Society of Canada’s Observer’s Handbook.

A few 7th-magnitude stars are also occulted, visible in small scopes as they disappear behind the Moon’s dark limb.

Rising Moon: Roll with it

A new year brings a new crescent. When the earthshine is prominent on the 2nd, pick out “Full Moon” features such as Tycho’s rays, brilliant Aristarchus, the aprons of Copernicus and Kepler, and of course the lunar seas. The jumble of bright and dark arcs of the foreshortened craters on the lit crescent can be a challenge to identify.

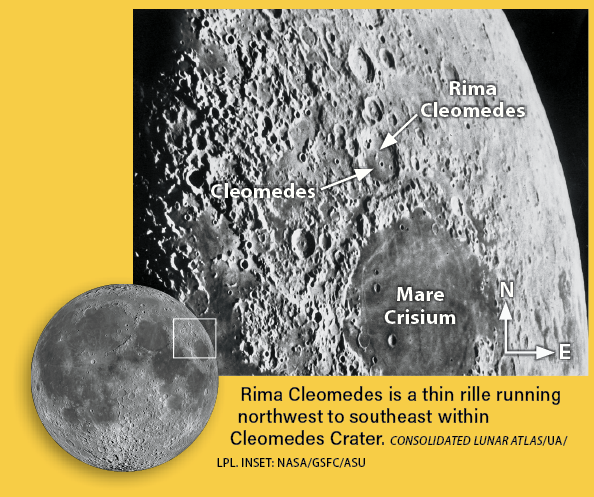

By the 3rd, the oval Sea of Crises north of the equator is fully illuminated. Cleomedes, named after a 1st-century Greek astronomer, is the large, 80-mile-wide crater adorning the north edge of Mare Crisium. An off-center hint of a central peak pokes out of the lava-covered floor, which is pocked by a couple of decent craters about 7 miles across. Kick up the magnification to seek out the long but thin rille, named Rima Cleomedes. Be patient for moments of clarity when the atmosphere above us steadies. These smaller features will disappear under a higher Sun on subsequent evenings.

Visible to the unaided eye over the next two weeks, Crisium seems to roll northward while the highlands climb away from the southern limb. Relative to Earth’s orbit on the ecliptic, Luna arcs above it enough for us to see “under her chin” — astronomers call this optical libration. From the 11th to the 15th, look for tall mountains and shadows at the lunar south pole.

You might be almost as captivated watching the sunset shadows swallow up the terrain in the evenings after Full phase on the 13th. The reversed lighting practically turns this into undiscovered country. Do it all again when the thin crescent returns on the 30th.

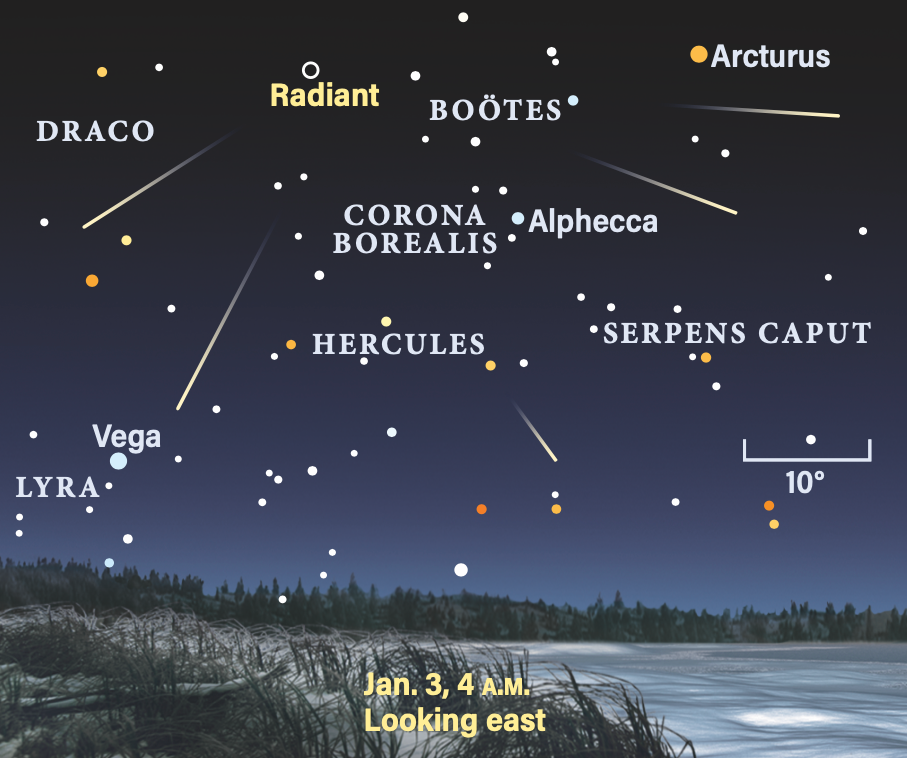

Meteor Watch: Starting the year off right

With a waxing crescent Moon in the early-evening sky, the conditions are set for the annual Quadrantid meteor shower. It peaks Jan. 3 and is best viewed in the hours before dawn.

The Quadrantids are active between Dec. 28 and Jan. 12, with a narrow peak. The radiant rises soon after 9 p.m. local time, and by 4 a.m. it’s about 45° high. Expect about 25 to 30 meteors per hour if the peak occurs during the dark window of your observing site, corresponding to a maximum zenithal hourly rate of nearly 100, making it one of the best showers of the year.

The Quadrantids’ parent object, 2003 EH1, was discovered in 2003 by Brian Skiff at Lowell Observatory.

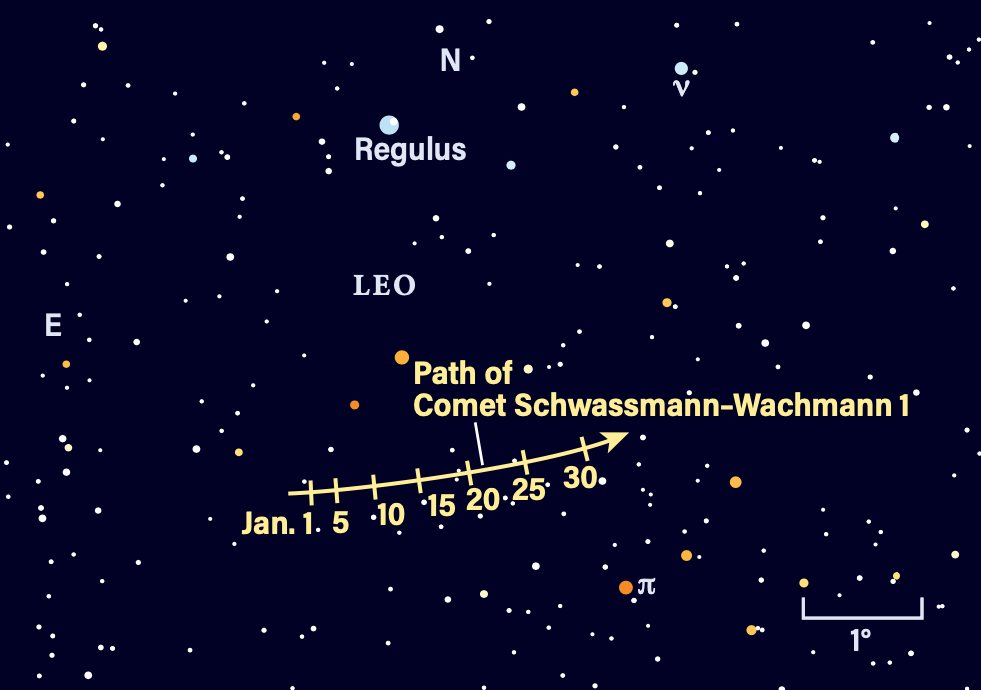

Comet Search: 2025 starts with hope

You know those nice comets that burst onto the scene with so little notice they beat the publication deadline? We’d appreciate three of those! This year, no currently known interplanetary snowballs are expected to glow brighter than 10th magnitude or be well placed.

Eager comet hunters with 8-inch scopes can test their skills to reach 333P/LINEAR at magnitude 10.5, but it requires a good star chart and ephemeris to nail it in the starry void. With respect to the North America Nebula (NGC 7000), the faint comet is west of Hawaii.

But luck could be ours a short 3° star-hop south of Regulus. Comet 29P/Schwassmann–Wachmann has, semiregularly, outburst from magnitude 15 to 10.5, then taken two weeks to fade back down. You’ll want at least 150x for the 1′- to 2′-wide patch to trigger a hit. Practice on the “other” Leo Trio — M105, NGC 3384, and NGC 3389 — the latter of which is a feeble magnitude 11.8, to calibrate yourself before going after the comet.

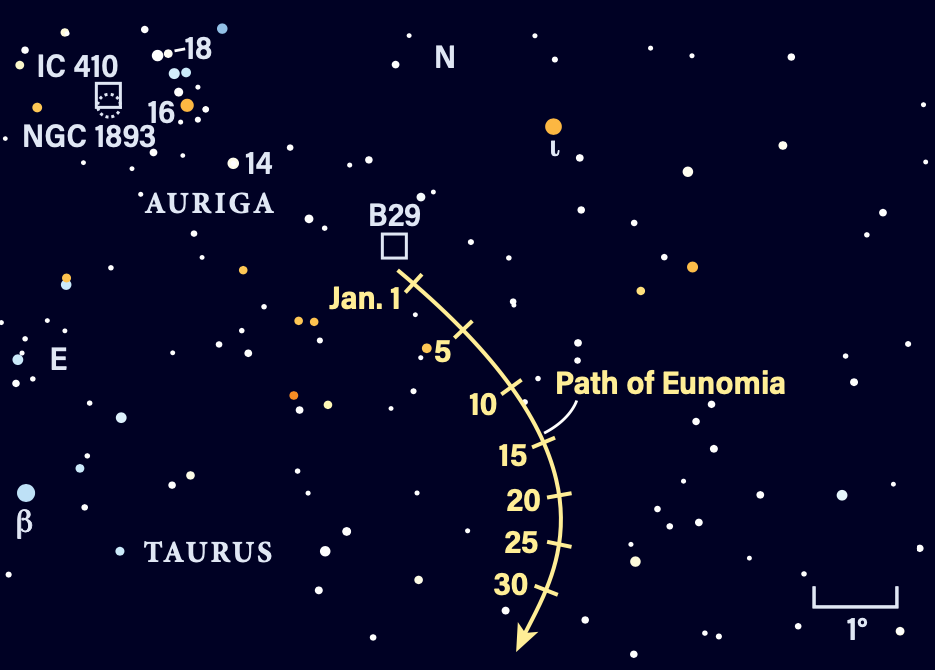

Locating Asteroids: Wandering down a dark alley

If we let them, asteroids may lead us along secluded paths that bring us across fascinating fields. From the suburbs, 15 Eunomia is our guiding light, reflecting our Sol to outshine most of the background stars of the outer Milky Way, much of which is obscured by vast, dusty domains. Only three stars are brighter in the vicinity.

Under a dark sky, a realm of stardust and tunnels appears in a wide-field eyepiece. Take your time to identify Eunomia by making a sketch of three or four of the brightest stars and coming back on another night to note its displacement. But the treasure here is found by simply sweeping the scope back and forth across and along the path. Just as easy as many Barnard dark clouds, here lie several Lynds objects.

Over on the south side of Castor on the 15th and cruising at 7′ per hour, 887 Alinda appears as a magnitude 9.5 dot that should be fun to follow in a 4-inch scope from the suburbs. Coming within some 30 times the distance of the Moon, this Amor-class rock never crosses our orbit — but it might in millions of years. At a bit more than a mile wide, a hit would mean a regional wipeout and a global food disaster.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 35° north latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

9 p.m. January 1

8 p.m. January 15

7 p.m. January 31

Planets are shown at midmonth