A total eclipse of the Moon is the highlight of this month, visible across North and South America. Venus remains very bright and transitions from evening to morning late in the month. Mercury joins Venus for a few evenings, offering the best opportunity to see both planets in twilight. Mars and Jupiter dominate the late evenings, providing many hours of planetary observation with tantalizing features to see in small scopes.

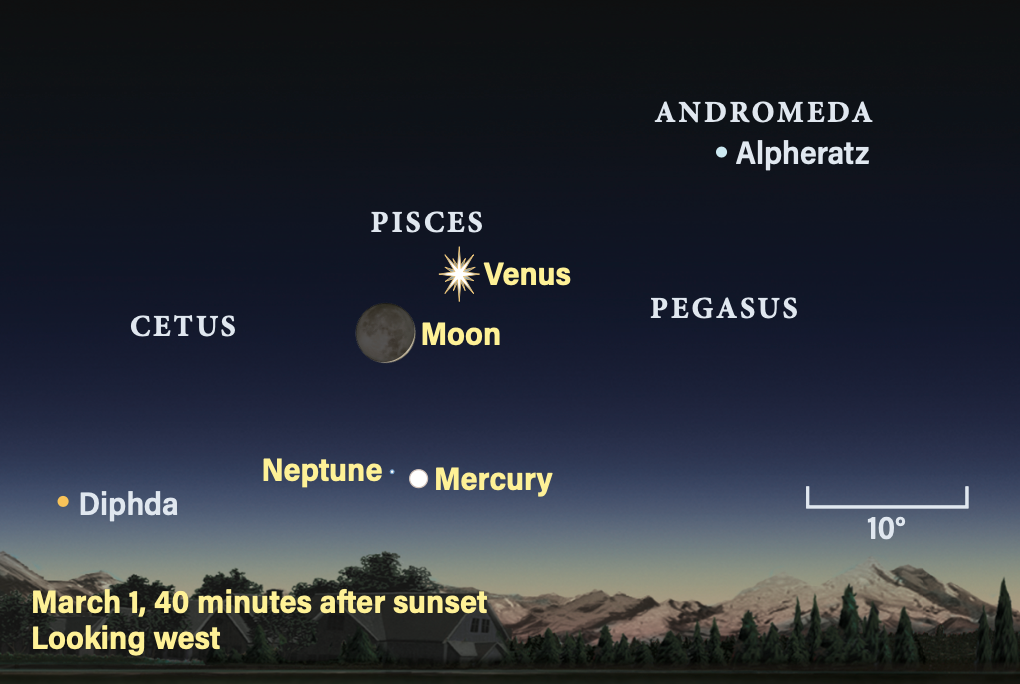

Both the inner planets, Mercury and Venus, stand together in the evening twilight during early March. Look for them soon after sunset. They will appear near the western horizon, so avoid any obstacles that may hamper your view.

Venus will be most obvious because it is so bright, shining at magnitude –4.8 on March 1. It becomes obvious within 30 minutes of sunset. On that date, a slender crescent Moon stands 6.5° due south (to the lower left) of Venus. Mercury, at magnitude –1, hangs nearly 10° below the Moon. Catch them all within an hour of sunset.

Watch Venus through a telescope this month. From the 1st to the 15th, the 49″-wide disk showing a 14-percent-lit crescent transforms into a 3-percent-lit crescent spanning 58″ — quite a dramatic change over two weeks.

Venus drops quickly into bright twilight in the third week of March and passes through inferior conjunction on the 22nd, standing some 9° north of the Sun. However, it is too dangerous to try and spot in daytime, due to the risk of sunlight entering your telescope.

Venus quickly reappears in the morning sky. By the 31st, it rises in the east an hour before sunrise. Through a telescope, its slender crescent now spans 57″ and is 4 percent lit.

Neptune, too faint to see (magnitude 7.8), stands 2° to the left (southeast) of Mercury on the 1st. It reaches superior conjunction with the Sun on the 19th. Saturn is also lost in the Sun’s glare and reaches superior conjunction on the 12th.

As March progresses, Mercury climbs higher to meet Venus. They appear side by side on the 13th, although Mercury has faded to magnitude 0.5 by this time; Venus is magnitude –4.4. They’re 5.5° apart. The alignment is a line-of-sight effect, as Venus stands closer to Earth (0.29 astronomical unit [AU]; 1 AU is the average Earth-Sun distance), while Mercury is on the far side of its orbit (at 0.77 AU). Both planets descend into twilight within a week, and we lose sight of them.

Uranus stands near the border of Aries and Taurus, crossing into Taurus on the 3rd. On March 4, a waxing crescent Moon stands nearby. Swing binoculars to the Moon and scan 4.5° south to spot Uranus, shining at magnitude 5.8. The 5th-magnitude star 63 Arietis lies half that distance from the Moon and provides a useful guide to find Uranus, which is 2.3° (a little over four Moon-widths) due south of the star.

By the 23rd, Uranus is 11′ due south of a 7th-magnitude field star. The planet dips low in the western sky by the end of the month. On the 31st, the crescent Moon is again rising to meet Uranus. The ice giant is 8° east of the Moon on this last evening of the month.

Jupiter shines brightly in Taurus the Bull, starting the month at magnitude –2.3 and dimming to magnitude –2.1 by the 31st. Jupiter moves east during the month, extending its distance from Aldebaran, the brightest star in Taurus, from 5° to 8°. A nearly First Quarter Moon stands 7° from Jupiter on the 5th.

Jupiter sets by 1 a.m. local daylight time at the end of the month and offers long evening views in small telescopes of its Great Red Spot, the twin dark equatorial belts, and other atmospheric features. Its disk spans 39″ on the 1st and falls to 36″ by the 31st, as the distance between Earth and the giant planet increases.

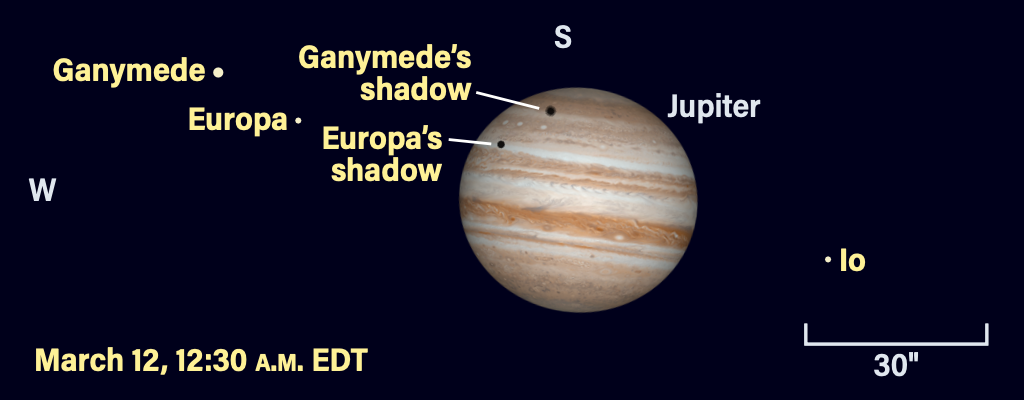

Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto orbit Jupiter with periods ranging from about two to 17 days. In addition to wandering east and west of the planet, they become hidden behind the disk or transit in front it. Their shadows appear as a black dot slowly moving across the cloud tops over a couple of hours.

Ganymede, Europa, and Io share a 1:2:4 resonance in their orbital periods, so similar events repeat. March 11/12 finds both Europa and Ganymede’s shadows on the disk at the same time, from about 11 p.m. to 12:45 a.m. EDT.

The eastern half of the U.S. sees Ganymede off the western limb, with Europa in transit. Watch the eastern limb of Jupiter for the appearance of Europa’s shadow around 10:15 p.m. EDT, around the same time Europa is exiting the disk. Next up is the giant shadow of Ganymede, which appears on Jupiter’s southeastern limb about half an hour later. It takes more than 10 minutes to fully appear. Europa’s shadow transit ends at 12:50 a.m. EDT, followed some 20 minutes later by the beginning of Ganymede’s shadow exit.

A week later, on the 18th, both moons transit the disk, starting with Ganymede around 9:30 p.m. EDT, as Europa hovers off the eastern limb. Europa begins its transit nearly an hour later, at 10:18 p.m. EDT. Meanwhile, watch Io disappear behind Jupiter’s western limb shortly after 10:50 p.m. EDT.

Ganymede ends its transit around midnight EDT. Watch the eastern limb for Europa’s shadow ingress at 12:50 a.m. EDT (now March 19 in the Eastern time zone), followed by Europa leaving the western limb five minutes later. These later events occur with Jupiter at low altitude or setting for the eastern half of the U.S.

The following night, March 19, Io is transiting the disk, visible for East Coast observers as darkness falls. Io leaves the disk around 10:20 p.m. EDT., with its shadow near Jupiter’s meridian. The shadow exits just before 11:40 p.m. EDT, visible across the U.S.

On the 25th, Europa and Ganymede again gather at Jupiter’s eastern limb, but their transits are only visible from the western half of the U.S. Europa’s transit begins just before midnight CDT; Ganymede’s begins around 11:40 p.m. MDT. Note how Europa has overtaken Ganymede since March 18, when its transit began nearly an hour after Ganymede’s. Now Europa leads by nearly 45 minutes.

Once again, Io follows a day later, with a transit starting at 10:05 p.m. EDT. Its shadow appears around 11:18 p.m. EDT.

On the 27th, Io and Europa reappear from the long shadow extending behind Jupiter. Io exits its eclipse at 10:45 p.m. EDT, about 20″ from the northeastern limb of Jupiter. Europa is following, but takes until 11:50 p.m. CDT to reappear, some 32″ from the same limb.

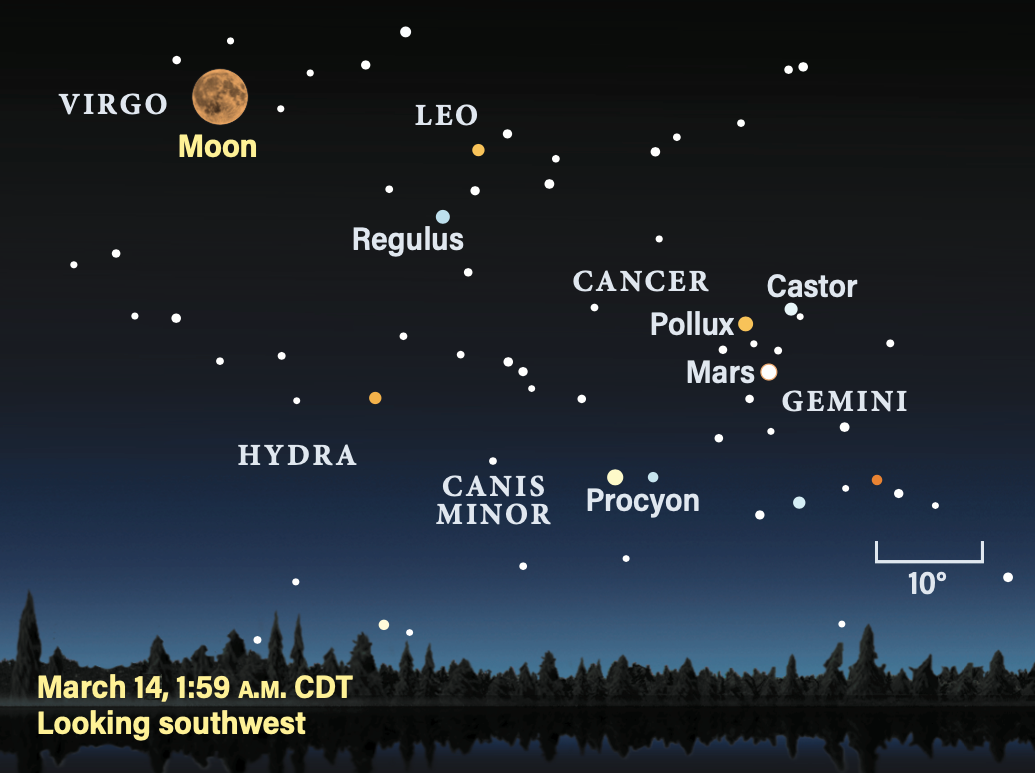

Mars is visible all night and stands high in the east at sunset, located in central Gemini. It forms a nice triangle with Gemini’s brightest stars, Castor and Pollux. The Red Planet shines at magnitude –0.3 on the 1st and dims to magnitude 0.4 by the 31st. A gibbous Moon stands some 2° northeast of Mars on the 8th. Mars stands 8′ northeast of 5th-magnitude 57 Geminorum on March 15th.

Telescopic views become more challenging as the distance to Mars increases. Its apparent diameter shrinks from 11″ to 8″ during the month, placing the planet well past its best. Very noticeable is the accompanying change of phase, as Mars diminishes from 94 percent to 90 percent lit.

Features on Mars become more difficult to make out as the disk shrinks. Can you see the North Polar Cap? It is melting as Mars moves toward northern summer. During March it may change quickly.

The first week of March is the best time to view the darkest feature on Mars, Syrtis Major. On the 1st, it’s visible as soon as it’s dark and rotates off the disk within a few hours. By the 7th, Syrtis Major is on the eastern limb of the planet at dusk across the central U.S. Over the next eight hours, you can follow it to the western limb.

Once Syrtis Major has gone, the fingerlike dark feature Sinus Meridiani appears at the eastern limb. As March progresses, this feature appears later each night.

During the last week of the month, the Tharsis ridge and Olympus Mons face Earth. By the end of March, the Solis Lacus region, including Valles Marineris, returns to our view.

This month’s total eclipse of the Moon occurs March 13/14, visible across North and South America. It’s also visible near dawn across the U.K., Ireland, Spain, Portugal, and parts of western Europe. The Moon lies near the border between Leo and Virgo.

A total lunar eclipse is the result of the Full Moon passing directly into Earth’s shadow. It’s a fine alignment that doesn’t occur every month because of the Moon’s 5° orbital tilt.

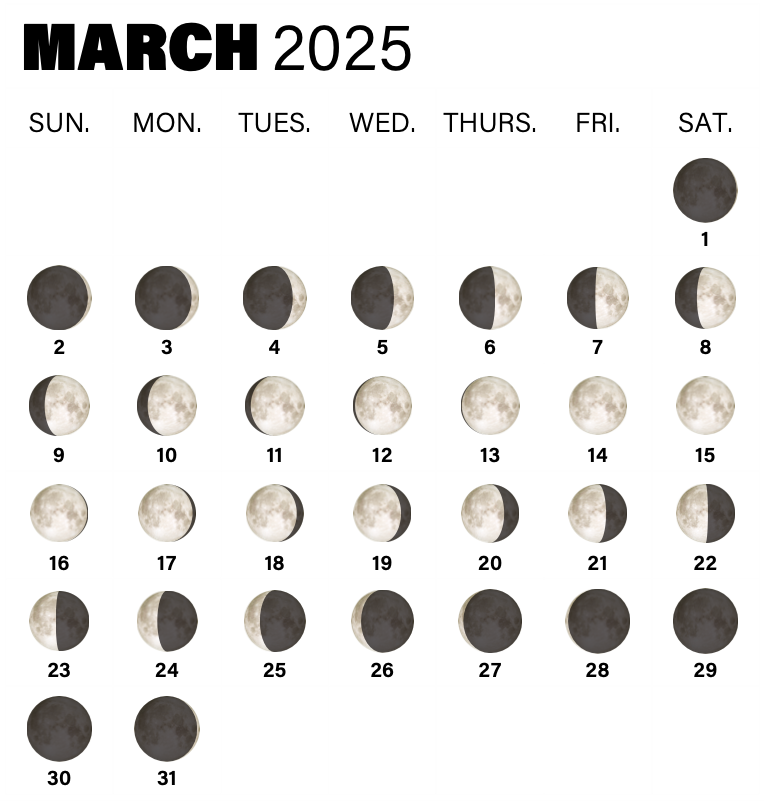

The barely noticeable penumbral stage begins just before 11:56 p.m. EDT. Gradually the southeastern limb of the Moon becomes dusky, until the Moon enters the main shadow at 1:09 a.m. EDT.

The partial phase gradually covers each crater in progression, and soon the dark shadow takes on a deep orange glow, with photographs easily revealing color. It’s the result of sunlight filtering through Earth’s atmosphere, which scatters blue light and allows red light to continue on to the lunar surface. This initially subtle coloration is particularly noticeable through a telescope. The color of the eclipsed Moon can vary between a dusky gray to a brilliant orange, dependent upon the state of Earth’s atmosphere.

The latter half of the partial phase is stunning, as many stars come into view as the Moon darkens further. Totality begins just after 2:25 a.m. EDT and greatest eclipse occurs at 2:59 a.m. EDT. The Moon is crossing the northern part of Earth’s shadow, resulting in some 66 minutes of totality.

Totality ends at 3:32 a.m. EDT, and the final partial phase progresses until 4:48 a.m. EDT. The final penumbral trace leaves the disk by 6:02 a.m. EDT.

It’s a perfect eclipse for photography. Wide-angle lenses capture constellations, with the orange Moon hanging like a lantern in the sky. Telescopic images reveal low-contrast craters on the Moon bathed in the orange glow.

Note that many states in the U.S. change to daylight saving time on March 9.

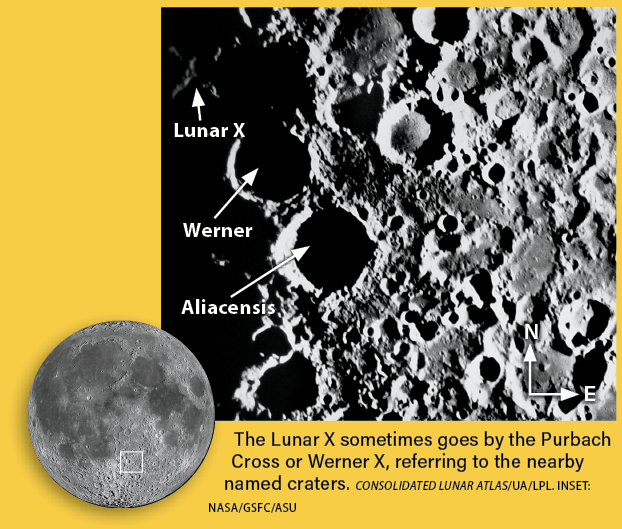

Rising Moon: X marks the spot

Observers in North America are perfectly placed to watch a few points of light on the Moon evolve into a prominent letter X on the evening of the 6th. It’s just a chance alignment of light and shadow as the Sun rises over a group of crater walls, but fun to see because it tickles our pattern-recognition fancy, called pareidolia.

If you take video clips every five to 10 minutes, you can create a time-lapse movie of the X emerging, peaking, and disappearing all in one evening. In the east, start looking soon after sunset. Focus in on a spot about halfway between the equator and the south pole, using the twin craters Aliacensis and Werner as your guide to the X, just to their northwest.

Watch points of light evolve into arcs, then full circles all up and down the terminator.

Meteor Watch: Dusty glow

Early spring is not well known for meteor showers, with no major events occurring this month. It is, however, a great month to spot the zodiacal light. The best opportunities occur when the Moon is out of the way, in the first three days of March and again during the last two weeks of the month.

Look for a delicate cone-shaped glow extending above the horizon through Pisces, Aries, and Taurus. Try using peripheral vision to spot the arching cone of light by scanning your eyes left to right along the western horizon. You’ll need a clear, dark horizon unaffected by lights or distant city glows, which mask the effect.

The zodiacal light is aligned with the ecliptic, Earth’s orbital plane, and comes from sunlight reflecting off fine, dusty debris littering the inner solar system, left over by passing comets long ago.

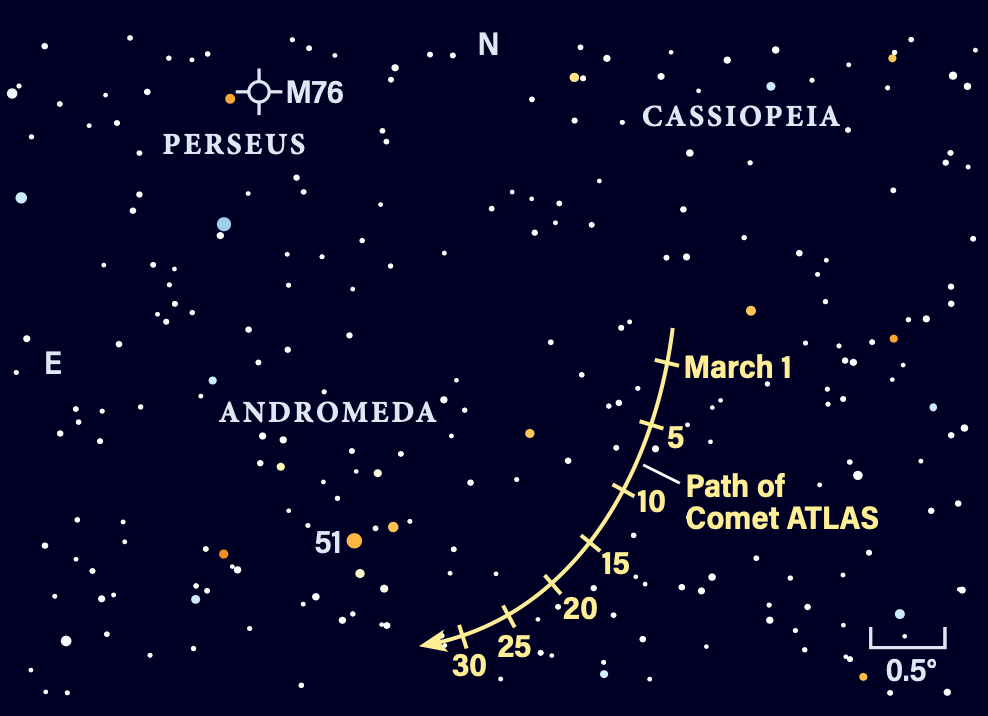

Comet Search: Plumbing the Depths

The popularity of the deep sky increased as larger scopes became affordable, inspiring comet fans to coin their viewing as “shallow-sky,” perhaps to entice galaxy fans to check out our solar system’s primordial snowballs. However, the only known comets coming up will require 10-inch or larger scopes to go deep from a dark site.

C/2022 E2 (ATLAS) is a 12th-magnitude pollen puff floating near the butterfly-winged nebula M76. Its curving trajectory keeps it within 2° of 51 Andromedae, which glows an easy magnitude 3.6 in any finder scope. Zero in on the field and push the power past 150x, even to 250x. The overall view will be darker, but the 1′- to 2′-wide comet then has a chance to tickle the dark-adapted rods of your retina.

Perhaps start to the southeast with the spectacular 10th-magnitude edge-on NGC 891 near Gamma (γ) And, and its companions NGC 910 and NGC 911, glowing at magnitude 12.3 and 12.7, respectively.

And drop in on 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann in Leo — it could be in outburst at 11th magnitude. Take in some color along the way, from blue-white Regulus to orange R Leonis, the latter of which is 1.5° north of the comet in early March.

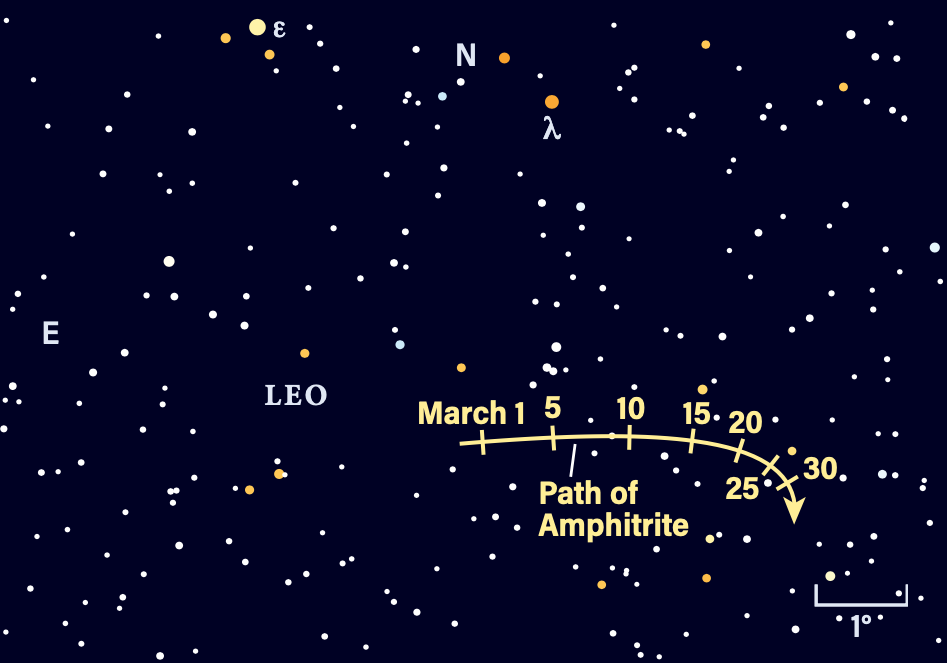

Locating Asteroids: Lounging with Leo

Regulus is the sparkling beacon in the east almost halfway up the sky during March evenings. Also known as Cor Leonis, the heart of the Lion, Regulus anchors a pattern of stars called the Sickle, which for modern observers resembles a backwards question mark. (Few folk these days have held a sickle, a common tool of farmers of the past.)

29 Amphitrite sports a diameter of 124 miles, shining with reflected sunlight at magnitude 9.5, and this month curves 4° south of Lambda (λ) Leo. Far from the Milky Way, the background here is sparse, making pattern recognition easy to identify the space rock. On the 9th, Amphitrite looks like the fainter component of a wide double, sitting just over an arcminute from an 8th-magnitude field star. Return three hours later to see that it has almost doubled that separation.

Named for a sea goddess in Greek mythology, this classic main-belt asteroid orbiting beyond Mars was discovered by German astronomer Albert Marth while working in London on March 1, 1854.

While you’re at the neck of the Lion, drop by Gamma (γ) Leo, one of the sky’s showcase double stars, a striking pale orange sun across a 5″-wide gap from a gold spot.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 35° north latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

10 P.M. March 1

10 P.M. March 15

9 P.M. March 31

Planets are shown at midmonth