November brings many sights to explore, including Mercury in the early evening, Mars brightening, and the giant planets Jupiter and Saturn adding to the spectacle. Jupiter in particular is reaching its best apparition in a decade for Northern Hemisphere observers.

Let’s start soon after sunset. Mercury hugs the southwest horizon and remains easily visible throughout the first half of the month, a steady magnitude –0.3. The planet is 2° high 30 minutes after sunset on Nov. 1.

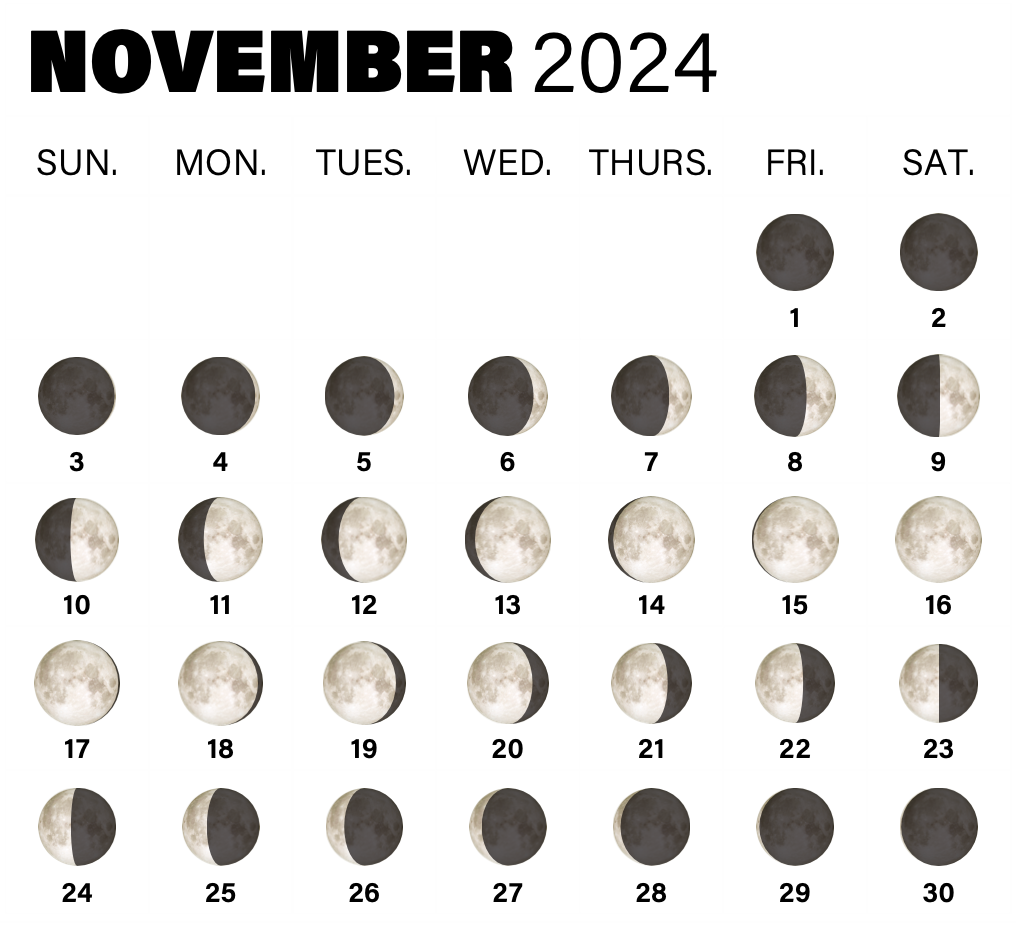

On Nov. 3, look for the waxing crescent Moon low in the southwest 30 minutes after sunset. Binoculars will show 1st-magnitude Antares, the brightest star in Scorpius, just off its northern limb, while Mercury stands 8° to the right of the Moon (just over one field of view in 7×50 binoculars).

By Nov. 9, Mercury stands 4° above the horizon at the same time. It is now 2° north of Antares. In bright twilight, however, binoculars will still be needed to spy the star to the lower left of Mercury.

Mercury wanders through southern Ophiuchus, reaching its greatest eastern elongation on the 16th, 23° east of the Sun. It sets a little over an hour after sunset. This is the best Mercury will be this month. A telescope shows a 62-percent-lit disk spanning 7″. By the 20th, Mercury is exactly 50 percent lit.

After that, Mercury begins to dim in earnest. By the 23rd, it shines at magnitude 0. A week later it’s plummeted to magnitude 1.4 and is lost from view.

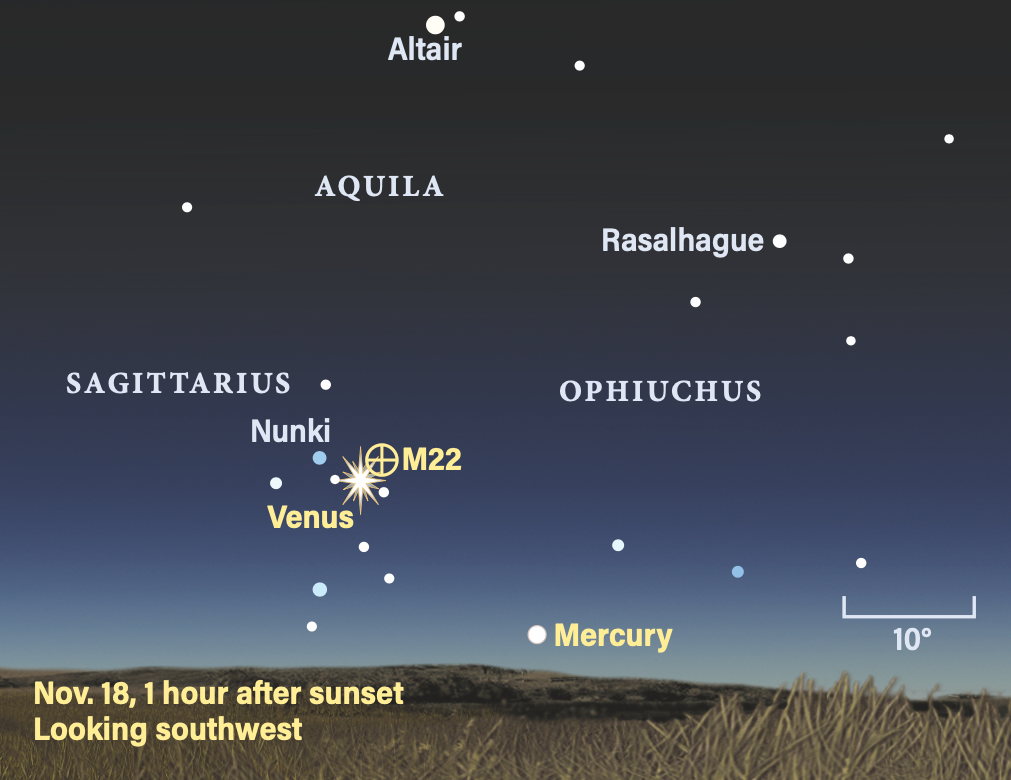

Venus treks across the Milky Way and is easy to spot soon after sunset, starting the month at magnitude –4. Check out the planet an hour after sunset with Ophiuchus as a backdrop in the darkening sky. Venus remains visible about two hours after sunset.

Venus stands 4° due north of a waxing crescent Moon on the 4th, an ideal evening to photograph it along with the Milky Way. A telescope shows a 76-percent-lit disk spanning 15″.

Venus crosses into Sagittarius on the 8th. By the 11th it stands 1.5° south of M8, the Lagoon Nebula. Grab binoculars for a stunning view. On Nov. 18, scan 1.6° north of Venus to spy M22, one of the finest globular clusters in Sagittarius, glowing at 5th magnitude.

By the end of November the planet has gained 0.1 magnitude and remains up 3 hours after sunset. A telescope shows a 17″-wide disk now 68 percent lit.

As nightfall descends, Saturn stands high in the southern sky among the faint stars of Aquarius. It shines at magnitude 0.8. It’s perfectly placed for observation, remaining above 35° in altitude for a few hours. It stays within 2° of Lambda (λ) Aquarii all month.

A 10-day-old Moon wanders close to Saturn on Nov. 10. At 8 p.m. local time on the East Coast, Saturn is 1° north of Moon. By 8 p.m. local time on the West Coast, the Moon has moved to sit 1° east of Saturn.

Saturn’s rings appear gossamer-thin to us now. This month the planet’s tilt reaches 5.2°, the widest since March, and the narrow axis of the rings spans 3″. The long axis stretches over 10 times that: roughly 40″. By the end of this year, the tilt diminishes again to 3.9°. Saturn’s disk also shrinks this month, from 18″ to 17″, while its polar diameter dips to 16″.

Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, is an easy target for any telescope, at magnitude 8.5. It stands near the planet Nov. 3/4, 11/12, 19/20, and 27/28.

The smaller inner moons undergo transits, although these are difficult to see visually. Combine a telescope larger than 10 inches with high-speed video capture and good seeing for a chance at viewing these events.

Tenth-magnitude Tethys transits beginning in the evening on Nov. 7, 9, 24, and 26. Similarly bright Dione undergoes transits the evenings of the 4th, 15th (visible only from the eastern half of the U.S.), 23rd, and 26th. On the 23rd, Rhea transits the southern pole of Saturn prior to the Dione event. On the 26th, Dione leads Tethys across the disk. Not all events are listed.

Iapetus is close to Saturn the evening of Nov. 1, as it passes through superior conjunction. It lies 43″ due south of Saturn, glowing near 11th magnitude. Track Iapetus until it reaches eastern elongation 8.5′ east of Saturn on the 20th, when it glows near 12th magnitude.

Neptune is in Pisces, well placed for evening observing some 14° northeast of Saturn and near the Circlet asterism. The distant planet shines at magnitude 7.7. Binoculars will show it forming a triangle with 20 and 24 Piscium, a pair of 6th-magnitude stars about 5° southeast of Lambda Psc in the Circlet. Closer to Neptune is a pair of 8th- and 9th-magnitude stars sitting side by side. The planet’s motion relative to these is evident from night to night.

A telescope reveals a 2″-wide disk with a bluish hue. A telescope is also needed to watch the Moon hide Neptune in an occultation the evening of Nov. 11, best seen from the eastern half of the U.S. Twilight will interfere farther west. The International Occultation Timing Association provides local timing of the event at www.lunar-occultations.com/iota/planets/planets.

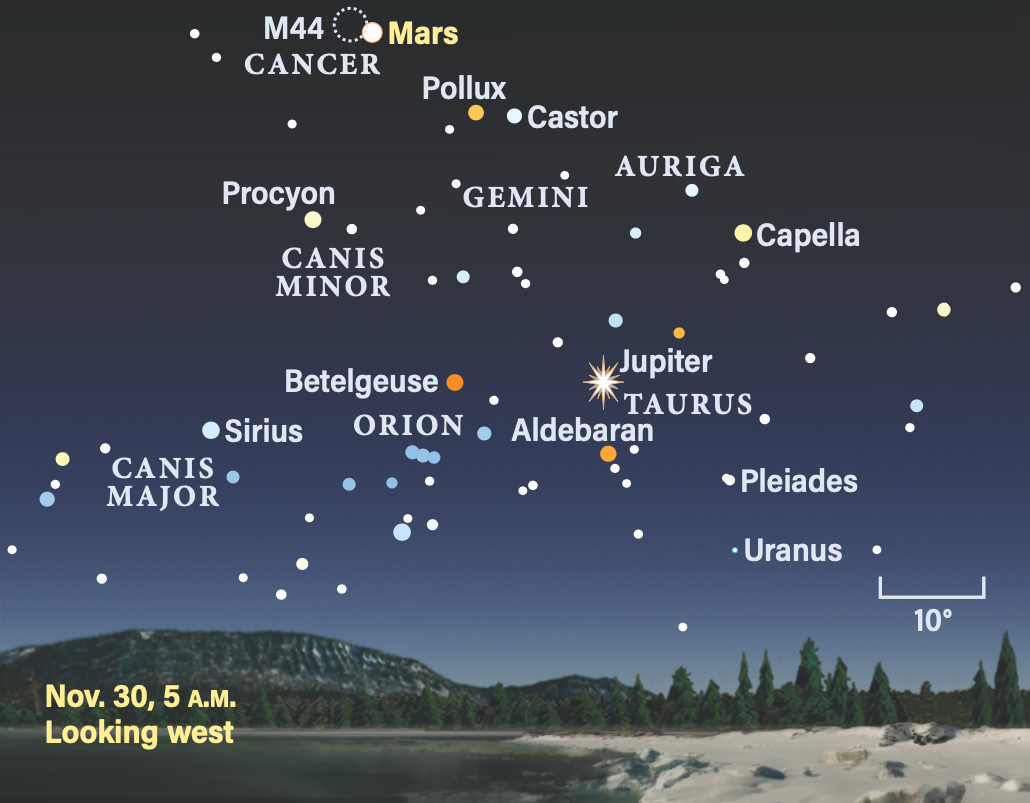

Uranus reaches opposition Nov. 16 and is visible all night. It’s in western Taurus, about 6.5° southwest of M45, the Pleiades. At opposition, Uranus stands due south at local midnight; the planet rises by 7 p.m. local daylight time on the 1st and three hours earlier (after the change to standard time) by the 30th. It moves slowly retrograde this month. The pre-dawn hours are a great time to view Uranus’ 4″-wide disk with a telescope.

The easiest way to spot the magnitude 5.6 planet is with binoculars. Scan south of M45 to find 6th-magnitude stars 13 and 14 Tauri, aligned east-west. Uranus is 2.3° west and slightly south of 13 Tau on Nov. 1. The gap increases to 3.5° by the 30th. Uranus and 13 Tau are nearly the same brightness.

Jupiter rises by 8:30 p.m. local daylight time on Nov. 1 and by the 30th it’s already up as twilight falls. Moving retrograde through central Taurus, Jupiter dominates the night sky. It’s the best the gas giant has been for Northern Hemisphere observers in about a decade.

Jupiter brightens to magnitude –2.8 this month. At midmonth it stands 10° northeast of Aldebaran and nearly 19° northwest of Betelgeuse. A waning gibbous Moon joins Jupiter in Taurus Nov. 16 and 17.

Jupiter remains above the horizon for some 15 hours, allowing time to watch a full rotation (just under 10 hours) in a single night. By the 30th, the disk spans 48″. Any telescope will show the pair of cloudy dark equatorial belts straddling the equator. If the Great Red Spot isn’t visible, just wait a few hours. The wealth of detail visible is amazing — wait for those moments when our atmosphere settles and detail jumps out.

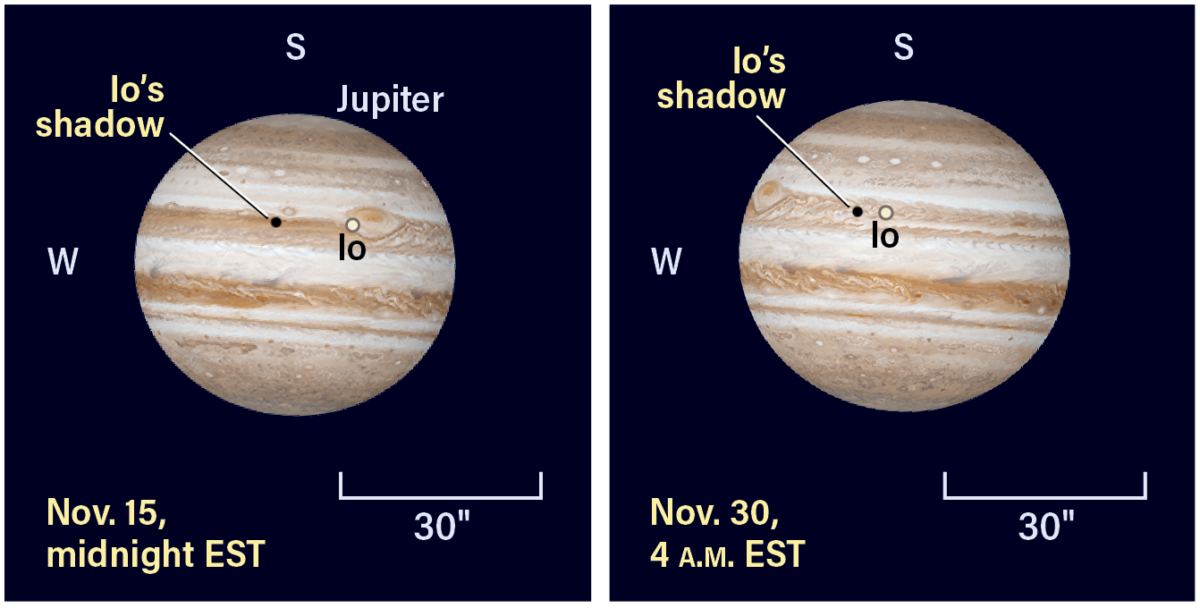

Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto transit in front of or become hidden behind the disk from time to time. Here’s a short review of some — but not all — of the month’s events.

On Nov. 2/3, the giant shadow of Ganymede crosses the south polar region from 10:39 p.m. to 12:44 a.m. EDT. The transit is underway as Jupiter rises for the Mountain and Pacific time zones. (Note: Clocks change to Standard Time at 2 a.m. on the 3rd.) Shortly after 1 a.m. CDT (also 1 a.m. EST), Ganymede itself transits.

Europa and its shadow traverse the planet Nov. 3/4. The shadow appears at 10:30 p.m. EST and Europa follows around 12:10 a.m. EST (on the 4th in the Eastern time zone only).

Ganymede and Europa repeat this sequence Nov. 9/10 and 10/11, respectively.

Io’s shadow begins a transit on the 15th at 10:45 p.m. EST, followed 33 minutes later by the moon itself. Notice the gap between the shadow and the moon — it’s diminishing as Jupiter approaches opposition. By Nov. 29/30, Io’s shadow appears at 2:35 a.m. EST, just 12 minutes ahead of Io itself.

Mars is growing in brilliance in the morning sky as it crosses Cancer the Crab. As November opens, Mars glows at magnitude 0.1; it brightens to magnitude –0.5 by the 30th. Mars rises around 11:00 p.m. local daylight time on the 1st. By the end of the month, the Red Planet rises at 8:30 p.m. local time and stands 40° high in the eastern sky at local midnight.

Mars passes 7′ north of 5th-magnitude Mu (μ) Cancri on the morning of the 2nd. Later in November, Mars stands 2° from the Beehive Cluster (M44). A waning gibbous Moon joins Mars in Cancer Nov. 20 and 21.

During the month Mars’ disk grows from 9″ to 12″ and increases from 89 percent to 93 percent lit. The tiny disk is strongly affected by turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere, but observing when Mars is highest in the sky (early morning) and using a high-speed planetary video camera can remedy this. Video capture takes practice — start now so you’re ready for opposition early next year.

The Red Planet stands 70° high in the southern sky at 5 a.m. local time, with the following features visible at that time (determined for the mid-U.S.): Nov. 1 (local daylight time), Tharsis Ridge; Nov. 4 (local standard time), Valles Marineris; Nov. 9, Sinus Meridiani; Nov. 16, Syrtis Major and the Hellas Basin; Nov. 24, Mare Cimmerium.

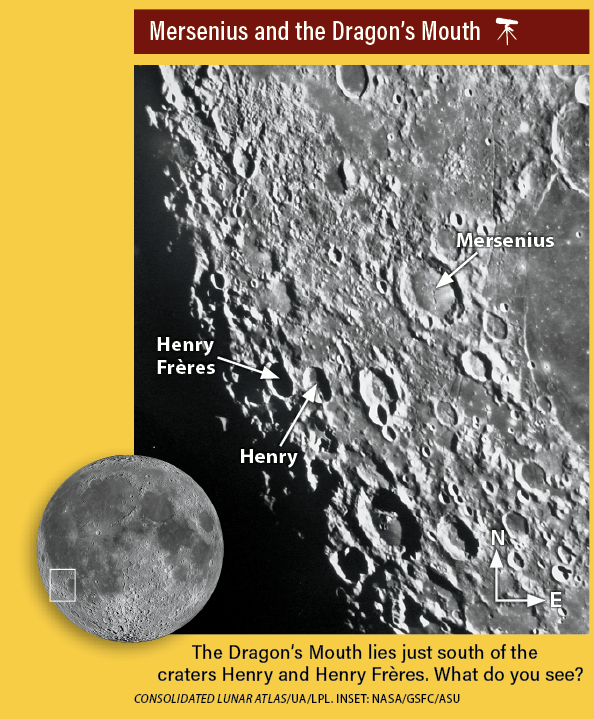

Rising Moon: Lava, volcanos, and a dragon

As bright as the Moon is on the 13th, darkness lurks along the terminator — perhaps there be dragons. The spackled strip of contrasts morphs with each passing hour. Tucked along the western shores of Mare Humorum in the lunar southwest is a broadly curving scarp centered on ground zero, where a massive impact formed the circular basin. As the Sea of Moisture sank under the weight of the lava, the floor cracked, leaving a nice cliff to catch the sunrise in a bright white arc. A smaller impactor arrived later to punctuate the scarp with a small crater.

Look for the couple of line segments on the west side, certainly not concentric to Humorum. They are part of a family of rilles that appear to be radial, like spokes on a bike, to a huge but now-buried basin. Deep cracks formed from that ages-old giant impact, then over time the walls slumped down and were further filled as later bombardments splashed material into them.

On the 13th, the modestly battered crater Mersenius is fully lit. A crater as wide as 50 miles ought to have a prominent peak, like the outstanding Tycho. It is there, but lies buried under lava that later oozed up through cracks in the floor in a most unusual way. Instead of being a flat pool, the surface is pushed upward in a broad dome, a bit puzzling to astronomers.

Can you see a Dragon’s Mouth tucked south of the pair of Henry craters? The play of light and shadows on peaks and crater rims in that location led observer Dave Gamble to imagine “a mouthful of very bright teeth.” They are nothing more than random mountain peaks and the mind’s fancy, but it’s fun to observe and talk about them, especially when the illusion may come and go in a half-hour.

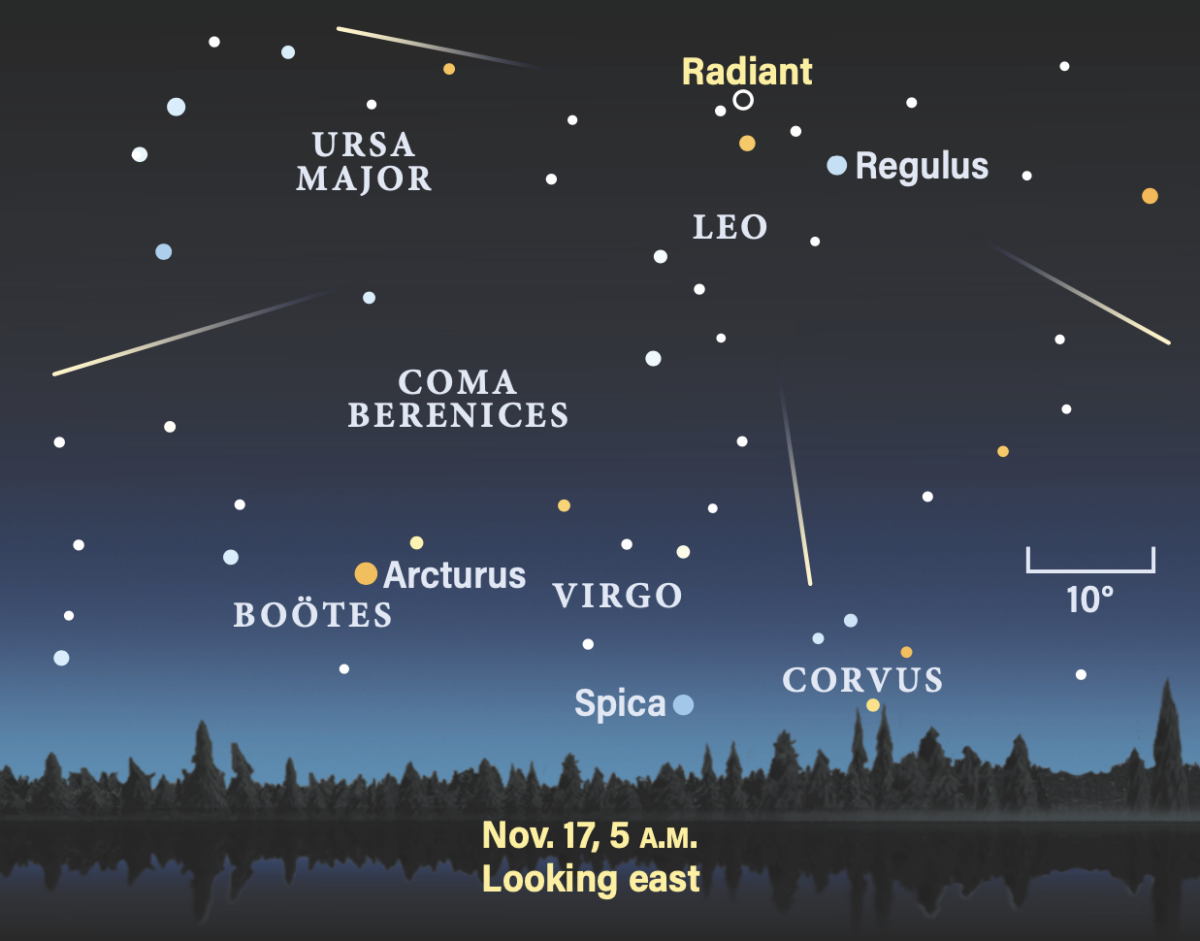

Meteor Watch: Aim to be early

The annual Leonid meteor shower peaks Nov. 17 and is active between Nov. 6 and 30. The Full Moon on the 15th affects the visibility of this shower, so conditions are unfavorable for the peak. The zenithal hourly rate of 10 meteors per hour this year means that even by Nov. 16, very few shower members will be seen. Observing in the week prior to maximum is likely best, as the Moon will set earlier in the night and Leo rises near midnight. On Nov. 10, the Moon sets at local midnight just as Leo is rising in the east.

The Leonid meteor shower is associated with Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, which last reached perihelion in 1998.

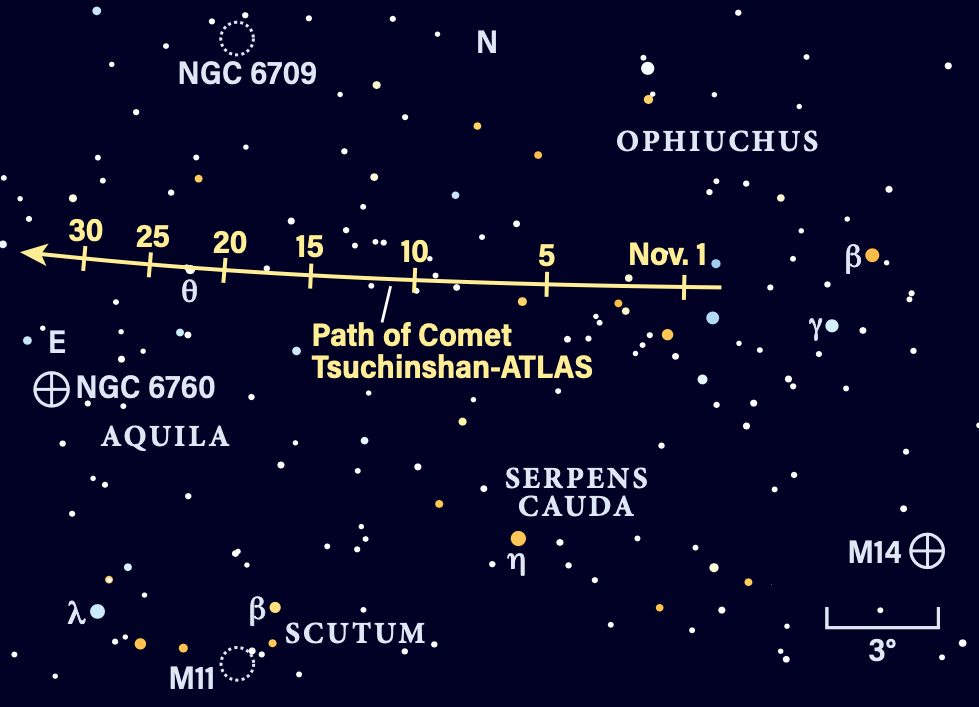

Comet Search: Binocular bonanza

Beginning Oct. 28 and lasting through the first week of November, a short celestial sword crosses some of the most wonderful binocular star fields in the sky. Step outside and enjoy Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) with unaided eyes and see it next to splashy open star clusters with binoculars or a small telescope.

Travel to a dark spot on the 8th and 9th; ignore those who disparage the First Quarter Moon’s light. If the sky is transparent, a 6th-magnitude comet will be a lovely binocular sight. Keep in mind it might be spring 2026 before we see another with unaided eyes.

Starting on the 19th, there’s a whole hour of darkness before the Moon rises. But the comet’s increasing distance from both Sun and Earth combine to quickly fade it past 8th magnitude by month’s end as longer nights set in. Compare the fuzzball’s shape and light profile to globular clusters M14 and NGC 6760. Which one is most pinpoint toward the center?

First detected only 21 months ago, Tsuchinshan-ATLAS reminds us that the comet of the decade could still be looping in from the depths, awaiting discovery.

Locating Asteroids: Try your luck

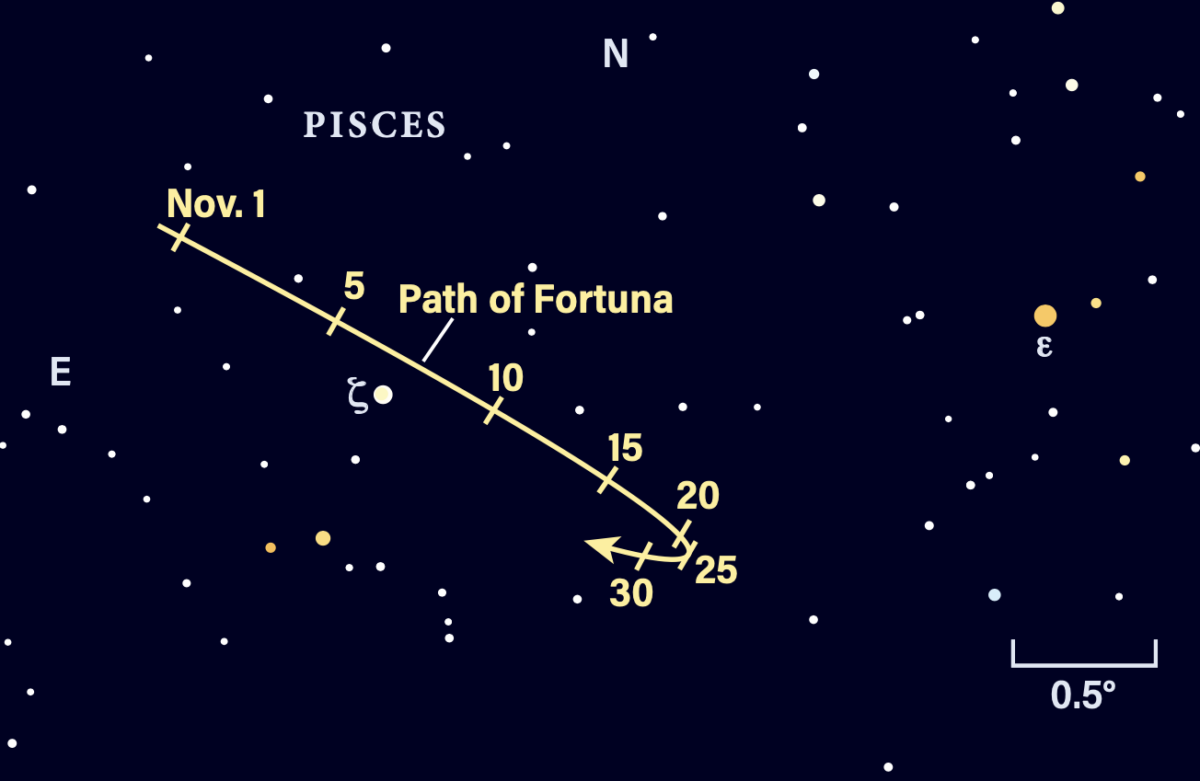

By a stroke of luck, main-belt asteroid 19 Fortuna lies less than 2° from the showcase double star Zeta (ζ) Piscium. Easy at 25x in a 60mm scope, the slightly unequal stars glow with off-white shades in larger scopes, historically ranging from yellow to rose to lilac.

If you’re star-hopping you’ll know you’re near the right spot because none of the other faintish stars of Pisces are similarly striking. From the suburbs, a go-to will really help. You’ll want a 4-inch scope to pull the 10th-magnitude rock out of the pale gray sky. Orient yourself with the 6th-magnitude field star to the southeast and an 8th-magnitude star to the northwest, both about 30′ away. Avoid the 11th through the 14th, when the Moon brightens the sky.

On the 5th, Fortuna forms an equal pair with a field star — Fortuna is the farther one from Zeta. It outshines any nearby stars on the rest of its track this month, except for the last week, when it fades below a 10th-magnitude star just to the south.

John Hind discovered Fortuna visually in 1852. It has a surface reflectivity darker than black dirt and is 140 miles across.