October finds Mercury and Venus in the evening sky. Mercury is shy and takes some effort to see, but brilliant Venus is not hard to find. Saturn, Neptune, Uranus, and Jupiter rise in that order before midnight. Mars becomes a fine bright object in the predawn sky, standing high in the east. And C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) may be on show as the comet passes closest to Earth and springs into the evening sky.

Mercury comes out of superior conjunction early in the month and by the 31st reaches an elongation of 18° east of the Sun. It stays very low above the western horizon due to the shallow angle of the ecliptic. By the 24th it remains difficult to spot, even at magnitude –0.4, since it sets 35 minutes after the Sun. Mercury’s visibility doesn’t improve much by the end of the month, as it dims by 0.1 magnitude and remains a mere 2° high 30 minutes after sunset.

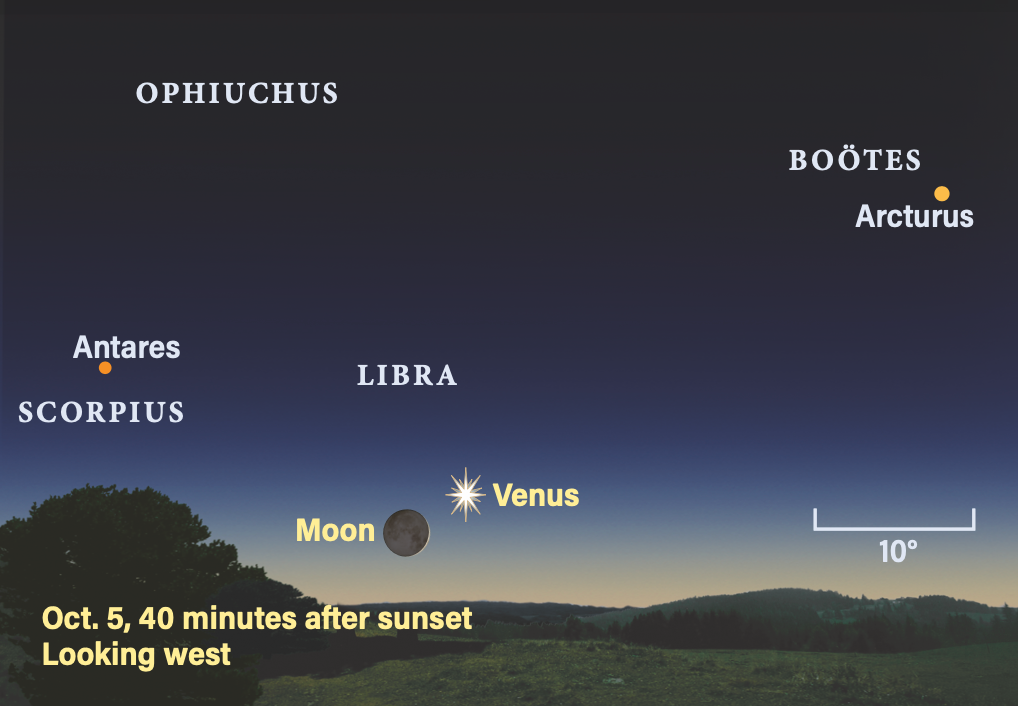

Dominating the evening is Venus, shining at magnitude –3.9 and more than 30° east of the Sun. You can use it as a guide to try and spot Mercury later in October by following a sightline down from Venus toward the direction of sunset.

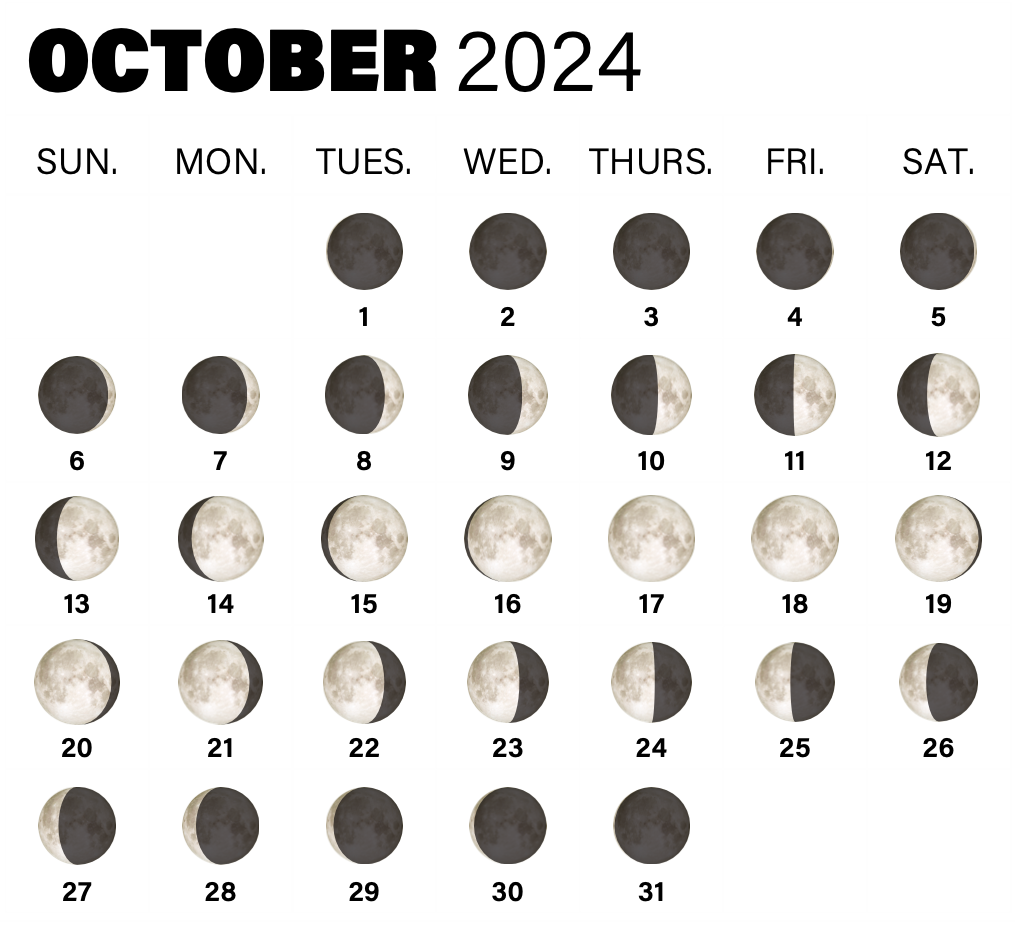

On Oct. 5, look for the thin crescent Moon less than 5° from Venus. Venus sets 80 minutes after the Sun in early October, offering a lovely view in deepening twilight. Through a telescope Venus is 12″ wide and 84 percent lit.

Mid-October will bring the highly anticipated Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS to the evening sky. It is 20° to 25° northwest of Venus on the 13th and 14th. Look for it in binoculars; by the time you read this, perhaps it could even be visible without aid. Time will tell, as comets rarely follow brightness estimates. Venus continues from Libra into Scorpius and then Ophiuchus. By the 25th, Venus stands 3° due north of Antares, a 1st-magnitude star dimly visible in evening twilight.

By the end of October, Venus has moved a bit closer to Earth, spanning 14″ and 77 percent lit.

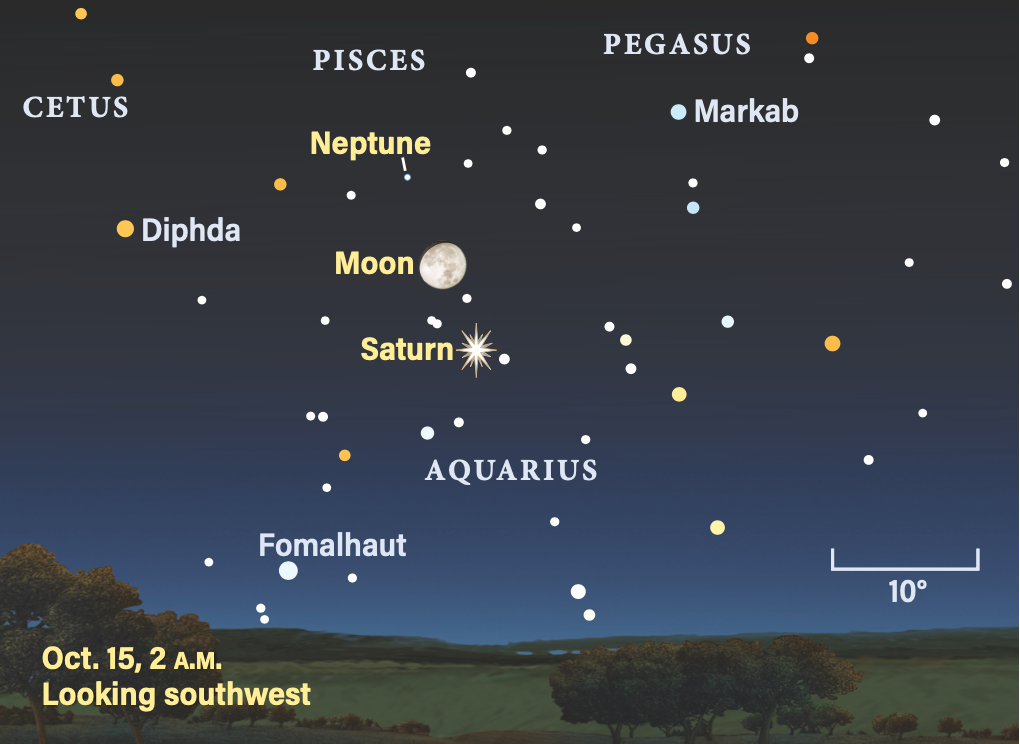

Already high in the southeastern sky as twilight falls, Saturn is ready for focused attention. By 8 p.m. local daylight time on the 1st, it stands 20° high among the stars of Aquarius. By the 31st, it’s some 40° high at the same time and remains visible well into the morning hours. It stands 2° from Lambda (λ) Aquarii, a 4th-magnitude star. Saturn spends most of the month at magnitude 0.7, outshining everything in this region including 1st-magnitude Fomalhaut, 20° south of the planet. It fades by 0.1 magnitude by the 31st, when it is 842 million miles from Earth.

Saturn’s shadow falls on the rings with increasing prominence throughout the month as the planet moves away from opposition. The tilt of the rings reaches 5° during October and will increase for one more month before beginning to narrow in the lead-up to the ring plane crossing next March.

The apparent size of Saturn’s disk through a telescope diminishes from 19″ to 18″, while its squashed polar diameter drops to 16″. The rings’ major axis of 43″ on the 1st shrinks to just over 41″ by the 31st.

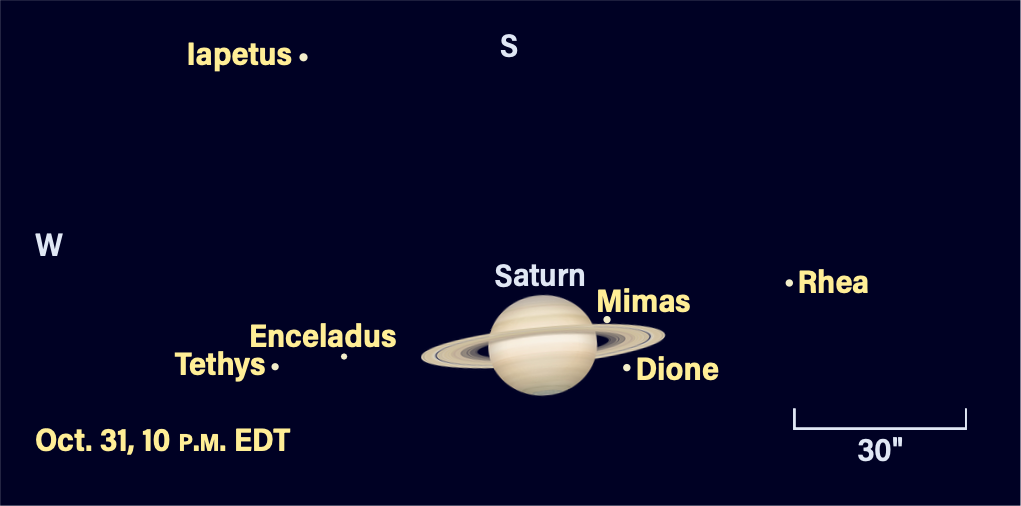

Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, is 8th magnitude — an easy target for any telescope. It stands near the planet Oct. 3, 11, 19, and 27, located just a few arcseconds off the northern or southern limb. It stands east or west of the planet Oct. 9, 17, and 25.

Look for 10th-magnitude Tethys, Dione, and Rhea orbiting from night to night, sometimes skimming the edge of the rings or undergoing transits and occultations. Telescopes larger than 10 inches using high-speed video capture under good seeing conditions have a chance.

Iapetus reaches its brighter western elongation Oct. 13, shining near 10th magnitude and 9′ due west of Saturn. It spends the rest of the month moving toward superior conjunction and is less than two days shy of this on the 31st, when it stands 1′ southwest of Saturn — a great time to spot this unusual moon. Its darker face has progressively turned our way, so it has dimmed by about a full magnitude.

Neptune rises before sunset and is well placed in the southeastern sky by full dark, gaining altitude through midnight.

During October, Neptune wanders west and forms a nice triangle with 24 and 20 Piscium, which lie just over 5° southeast of Lambda Psc. Follow Neptune’s motion relative to these stars through binoculars. Around mid-month, you’ll find the 8th-magnitude planet 1° due north of 24 Psc. A telescopic view reveals a 2″-wide disk with a distinctive bluish hue.

A waxing gibbous Moon stands about 10° southeast of Neptune on Oct. 14 and half that far northwest of the planet on the 15th.

Uranus rises by 9 p.m. local daylight time on the 1st, and two hours earlier by the 31st. It stands about 6° southwest of the Pleiades (M45) all month. The easiest way to spot it is with binoculars. Scan south of M45 to find a pair of 6th-magnitude stars, 13 and 14 Tauri, aligned east-west. Uranus stands 1.3° southwest of 13 Tau on Oct. 1, a gap that increases to 2.3° by the 31st. Uranus is the same brightness as 13 Tau: magnitude 5.7.

With Uranus high in the sky in the pre-dawn hours, it’s a great time to view the planet through a telescope. The disk spans 4″, revealing little to the earthbound observer but a nice challenge for video capture with telescopes 14 inches and larger.

Jupiter rises just after 10 p.m. local daylight time on Oct. 1 and two hours earlier on the 31st. Early morning sees Jupiter at more than 60° in altitude, a boon that offers stunning views for Northern Hemisphere observers. It’s located in Taurus and brightens to magnitude –2.7 this month. A waning gibbous Moon joins Jupiter Oct. 20 and 21; the Moon passes within 0.5° of Elnath, the northern horn of the Bull.

Even small telescopes can view detail in Jupiter’s turbulent atmosphere. On some nights the Great Red Spot appears, its motion evident within 10 to 15 minutes. The jovian disk starts October at 42″ and grows to 46″ by the 31st.

Galilean moons Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto transit in front of the disk or become hidden behind it from time to time. Here are some — but not all — of the month’s events.

The evening of Oct. 2 finds Europa’s shadow crossing the disk of Jupiter, starting around 11:48 p.m. EDT and ending at 2:18 a.m. EDT (Oct. 3 in all U.S. time zones except Pacific).

Ganymede takes many minutes to disappear behind Jupiter’s limb the night of Oct. 8/9 at 1:29 a.m. EDT. It reappears exactly two hours later. The large moon transits the southern polar region of the planet Oct. 26/27 from 10:35 p.m. to 12:40 a.m. EDT (ending after midnight on the East Coast only). The transit is underway as Jupiter rises in the Mountain time zone and the latter portion is barely visible from the West Coast.

By contrast, Europa suddenly reappears Oct. 11/12 at 1:30 a.m. EDT, popping into view at the eastern limb near the Northern Equatorial Belt.

Oct. 14/15 hosts Io and its shadow transiting the disk, with both visible for an hour starting around 4:23 a.m. EDT. Callisto is due south of Jupiter on the 15th at 6:30 a.m. EDT, missing the planet entirely. Io and its shadow repeat their journey Oct. 23/24, with both visible on the disk from about 12:37 a.m. and 1:48 a.m. EDT. And once again, you’ll find Callisto due south of Jupiter early on the evening of the 31st.

Mars rises shortly before local midnight on Oct. 1 and by 11 p.m. local daylight time on the 31st. The Red Planet tracks eastward across Gemini and moves into Cancer by the 29th. It starts the month at magnitude 0.5 and brightens to magnitude 0.1 by the 31st, standing on that date 7.5° southeast of Pollux. In the hour before dawn, Mars is an impressive 70° in altitude.

Mars’ disk reaches 9″ wide and 89 percent lit by the end of October. The Red Planet now reveals some of its surface secrets, hidden from Earth for more than a year. Now is the time to brush up on your video-capture and processing techniques before opposition in January 2025.

Mars stands high in the eastern sky at 4 a.m. local daylight time; the following features are visible at that time throughout the month (determined for the mid-U.S.): Oct. 3, Sinus Meridiani; Oct. 10, Syrtis Major and the Hellas Basin; Oct. 18, Mare Sirenum; Oct. 26, Olympus Mons; Oct. 31, Tharsis Ridge and Valles Marineris.

About an hour before sunrise, Oct. 1 hosts a fine crescent Moon and possibly Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS if it is bright enough. The comet sits 12° to the right of the Moon but is quickly affected by twilight, if it is visible. It crosses into the evening sky in the second week of October and quickly increases its elongation from the Sun.

The comet comes closest to Earth Oct. 12, at a distance of 43.7 million miles. After this, it could reach 1st or 2nd magnitude and be a lovely object in binoculars.

Rising Moon: Lava, lava, lava, dome

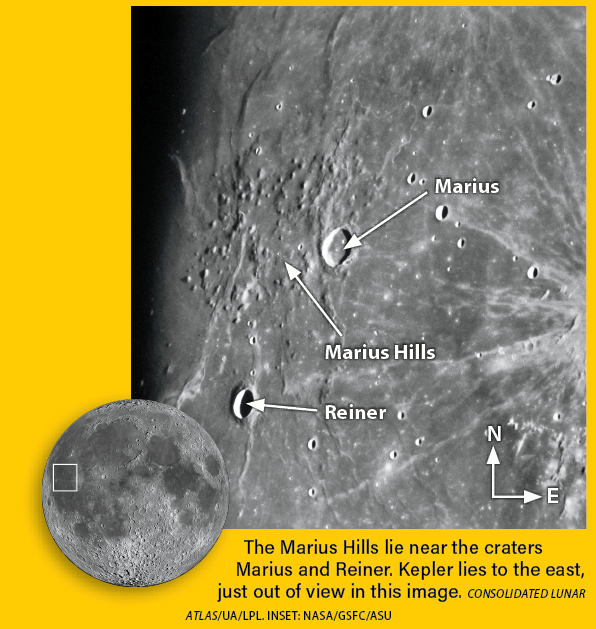

Among the best volcanic features on the face of the Moon (not counting the huge “seas”) is the field of domes known as the Marius Hills. Located in the vast Oceanus Procellarum basin near the craters Marius and Reiner in the lunar west, the coarse, sandpaper-like terrain sees first light about three days before Full phase.

The Moon is quite bright on the evening of the 14th — use a filter to reduce the glare, or even sunglasses will help. At first your eye will be drawn to Tycho’s spectacular ray system and then to brilliant Aristarchus, dominating Luna’s northern section at this phase. Have a look, but then shift your concentration to an area just north of the equator and boost the magnification.

How did the Moon develop this outbreak of hives? Astronomers reason that the evidence points at more than one episode. A few hundred steep-sided cone volcanoes erupted onto the scene when a huge zone of magma upwelled. Less violent eruptions then built the dome structures surrounding them. Finally, volumes of lava oozed out of cracks and vents to fill much of the vast basin surrounding the Marius Hills. To the first lunar observers, this huge expanse of darker, smoother terrain evoked a sense of the sea.

Under turbulent skies you might only see the two larger peaks. The Marius Hills will be harder to notice on the 15th, and by the 16th the higher elevation of the Sun will have wiped out the shadows necessary to observe textured terrain. Before moving on, take some time to admire the bright splash of rays from the relatively younger Kepler.

Meteor Watch: Fighting moonlight

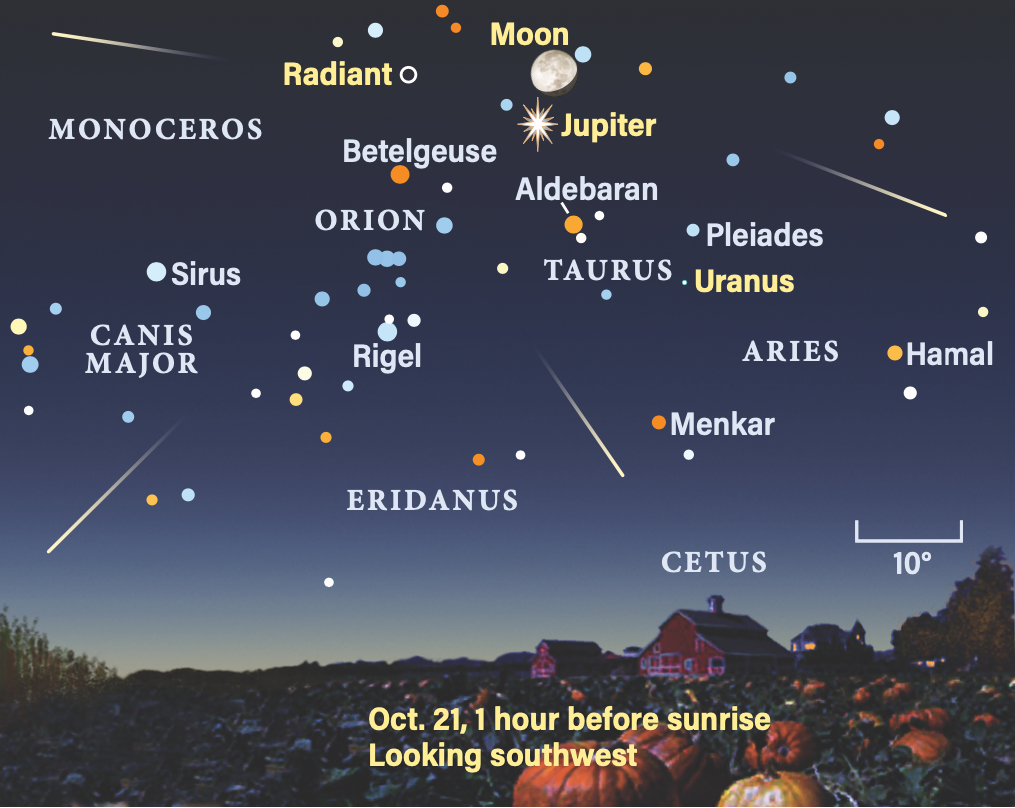

The remnants of Halley’s Comet generate the annual meteor shower called the Orionids. It’s active from Oct. 2 through Nov. 7, with the peak occurring on Oct. 21. A bright gibbous Moon located on the Taurus/Auriga border will strongly affect the appearance of Orionid meteors.

The shower has a zenithal hourly rate of up to 20 meteors per hour on the morning of maximum, corresponding to an observable rate of some 15 to 18 per hour between 2 a.m. and dawn. The radiant lies in northeastern Orion and rises by 10:30 p.m. local daylight time.

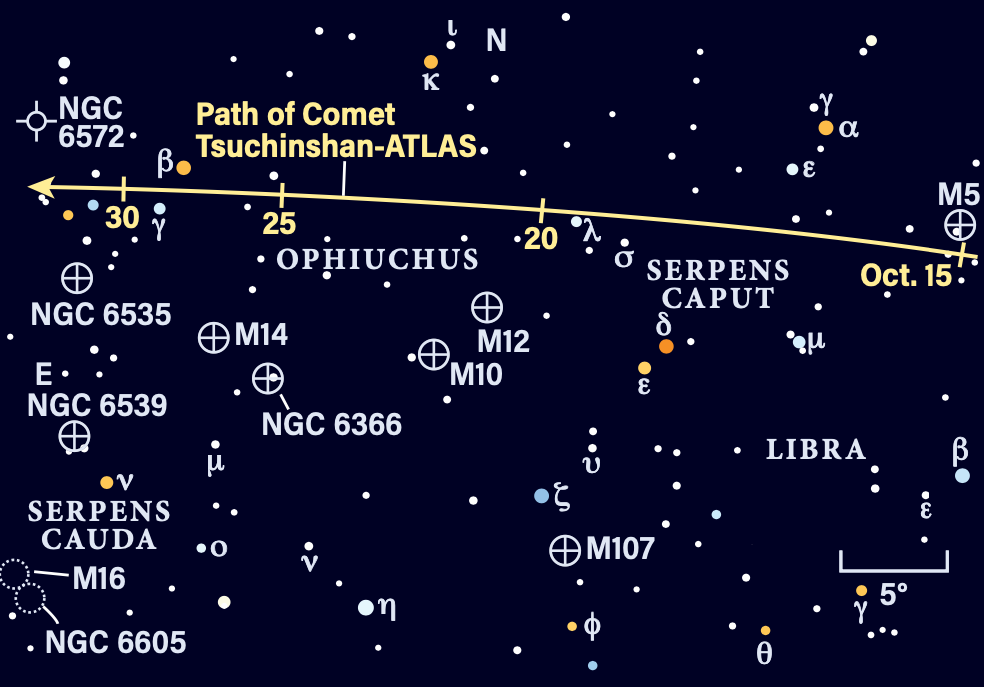

Comet Search: Comet of the year

Get out and enjoy Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS), whether with binoculars, a small telescope, or unaided eyes. It doesn’t matter if you’re in the town or country. Look often — it might peak and fizzle or split and surge within a day or two. Regardless, this comet will absolutely delight amateurs like us. It might even be the best of the decade, but not worth a last-minute plane ticket to the desert.

When September closes, the comet is at perihelion, closest to the Sun. The head is visible only as dawn breaks, with its tails streaming toward Sirius. What structures will be visible? Will we get a magnetic disconnection in the solar wind? By Oct. 7, follow it online through the field of view of NASA’s SOHO LASCO C3 for a few days.

Then get set … and go! On the 9th, scan the sky with binoculars shortly after sunset — if Tsuchinshan-ATLAS gets as bright as Venus (unlikely), you’ll see it! An hour later, the blue ion tail stretches up to Arcturus like an auroral spike. On the 10th, the comet’s head glows brightly in the deep twilight with the ion tail straight up. The dust tail should be super bright because of the forward-scattering effect when it lies between us and the Sun.

By the 13th we should see a sunward-pointing anti-tail forming. It’s a trick of perspective as Earth passes through the comet’s orbital plane on the 14th, the dust fan edge-on toward us. On this night, casual observers will discover another “comet” with their binoculars: the large globular star cluster M5. Imagers can nab fainter comet 13P/Olbers in the same field, quite an uncommon sight!

Never mind the glow from the Moon; use a telescope to study Tsuchinshan-ATLAS’ inner coma. There’s a decent chance to see a shadow channel projected onto the fan of dust. From the 20th onward, the Moon rises after the sky is fully dark, maximizing the contrast between the tails and the sky. Alas, the comet is fading, yet still visible to the unaided eye from a dark site.

Locating Asteroids: A joyous time

I love the fall season. Many long, sometimes mild, transparent nights are a gift after those short, summer nights of haze and smoky skies.

Main-belt asteroid 39 Laetitia, perhaps some 100 miles wide, glows at magnitude 9.5 due to reflected sunlight. It won’t present a simple “spot and run” observation, but as long as you make a basic sketch one night by dropping four or five dots into a logbook circle, the next time you return one of the points will have shifted. On the 11th and 12th, it sits inside a quadrangle of stars at low power, and moves just outside it by the 13th.

Some additional sunlight delight might pass through this month as you peer into the eyepiece. For Northern Hemisphere observers, dots will drift into and then pass out of view if your scope has a drive. These are geostationary satellites — they just happen to have solar panels reflecting the Sun to you at the perfect angle this month, perhaps reaching 3rd magnitude. Without a drive, the satellites appear stationary while the stars drift across.

Laetitia was named in honor of a minor Roman goddess whose realm was gaiety. So, have some fun out there!