Peak viewing season for the giant planets continues. Saturn is visible all night, at its best in the late evening. Jupiter rises later and dominates the early morning. Neptune reaches opposition near a 5th-magnitude star — grab binoculars to catch the best view of 2023. Uranus hovers between the Pleiades and Jupiter, offering good opportunities to catch this distant giant. Venus grows to greatest brilliancy before dawn — you can’t miss it — and Mercury comes up to join it later in September.

Mars is slowly approaching its November solar conjunction. Shining at magnitude 1.7, it’s a challenging object low in the western sky after sunset. Mars stands 3° high 30 minutes after sunset and drops to half that elevation less than 15 minutes later, so the observing window is very narrow. Look for Spica, which is brighter, located 12° east of Mars by midmonth.

The crescent Moon passes in front of Mars during a daylight occultation Sept. 16, visible across the U.S. The timing of the event varies with location. It’s midafternoon for the Eastern Seaboard (in Miami, Mars disappears around 3:25 p.m. EDT), and early afternoon for Midwestern states (12:26 p.m. MDT in Denver). Mars misses the southern limb of the Moon for observers along the West Coast except in the extreme northwest (e.g., Portland).

By evening, you can spot Mars nearly 2° west of the very thin, two-day-old Moon. The Red Planet soon dips out of view as it heads for the Sun.

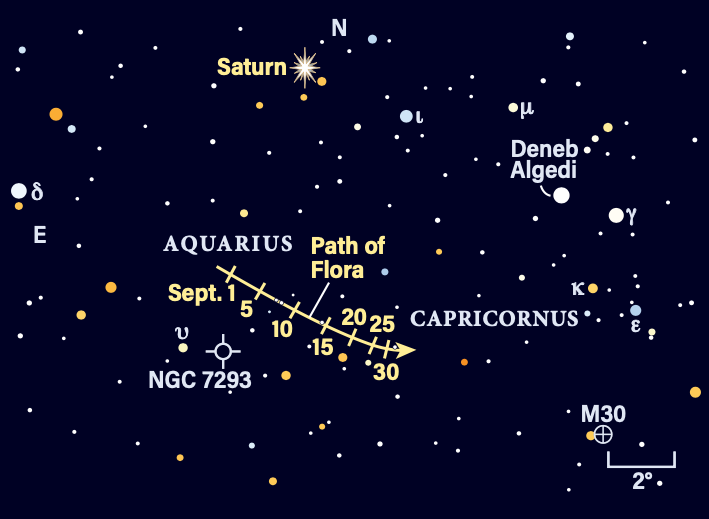

Saturn is at its finest in early September. It just passed opposition Aug. 27 and is visible all night in Aquarius. The ringed planet shines at magnitude 0.4 and dims 0.1 magnitude by midmonth. You’ll find it low in the southeastern sky after sunset; it climbs steadily to its highest due south around local midnight on Sept. 1. By the end of September, Saturn reaches this point two hours earlier.

A bright gibbous Moon lies about 3° below Saturn Sept. 26. With increasing darkness as the autumn Sun sets ever earlier, conditions are favorable for late-evening viewing.

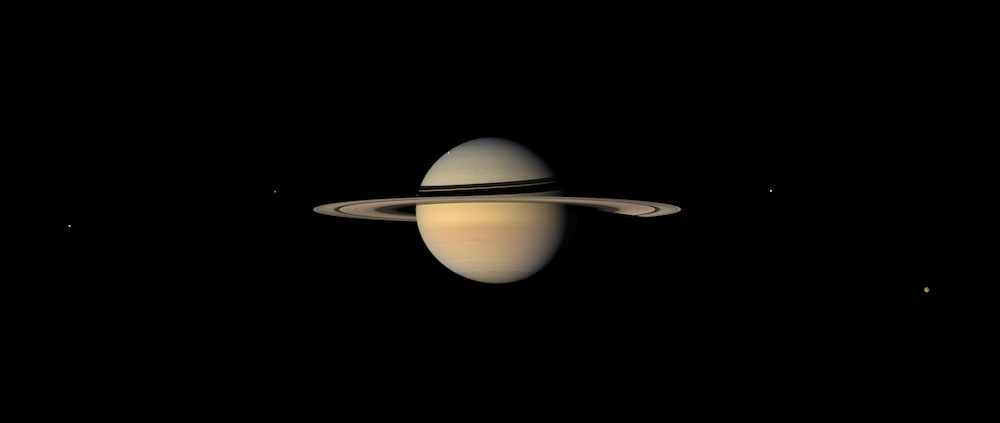

Through a telescope, the rings’ northern side is sunlit and tilted toward us by 9° in early September. The angle increases to 10° by the 30th. The dusky appearance of the outer A ring contrasts nicely with the brighter B ring. The two are separated by the dark Cassini Division. The inner C ring is lighter and transparent.

Saturn’s yellowish disk spans 19″ and the rings extend 42″. We’re viewing the world from about 8.8 astronomical units (818 million miles) away; this distance slowly increases throughout the month. (One astronomical unit, or AU, is the average Earth-Sun distance.)

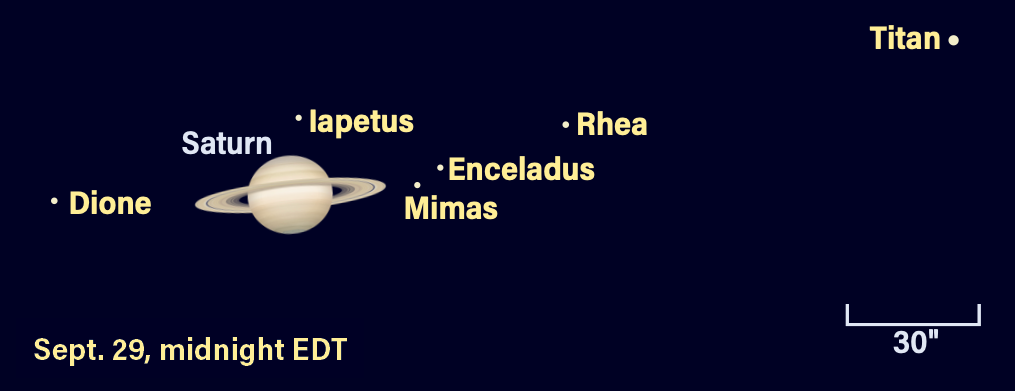

Saturn’s brightest moon is magnitude 8.5 Titan. Its 16-day period carries it roughly north of the planet from Sept. 7 to 8 and 23 to 24. It appears roughly south Sept. 15 and 16. Look also for three fainter, 10th-magnitude moons — Tethys, Dione, and Rhea — orbiting closer in. Rhea is a shade brighter than the other two. Tethys and Dione orbit in 1.9 and 2.7 days, respectively, while Rhea takes 4.5 days. Occasionally, bright field stars wander into view, so take care not to mistake these for moons. From Sept. 8 to 10, for instance, Saturn moves between an 8th- and 9th-magnitude stellar pair.

Enceladus is very faint at magnitude 12. It lies nearer to the rings, so Saturn’s brilliance makes it a challenge, but spotting it is a thrill.

Iapetus reaches western elongation Sept. 10, shining at 10th magnitude. It stands 9′ west of the planet, far beyond the other moons, making it trickier to identify. On Sept. 12, it lies between two 10th-magnitude stars. On Sept. 20, Iapetus appears double, sitting next to a magnitude 10.6 star. Watch for a few minutes and the moon will reveal itself by moving relative to the star. The following night, Titan sits beside the same star.

Iapetus moves toward Saturn, approaching superior conjunction on the 29th. Don’t confuse it for the 10th-magnitude star due west of Saturn on Sept. 26. Iapetus, fading as its darker hemisphere turns earthward, is closer to the planet. The night of Sept. 29, Iapetus is 17″ south of Saturn.

Look on Sept. 13 just before 11 p.m. EDT: Tethys begins to transit the planet, followed a few minutes later by its shadow. Good seeing conditions are needed to observe the event; the best way to record it is to capture high-speed video and process later. The transit lasts about 90 minutes.

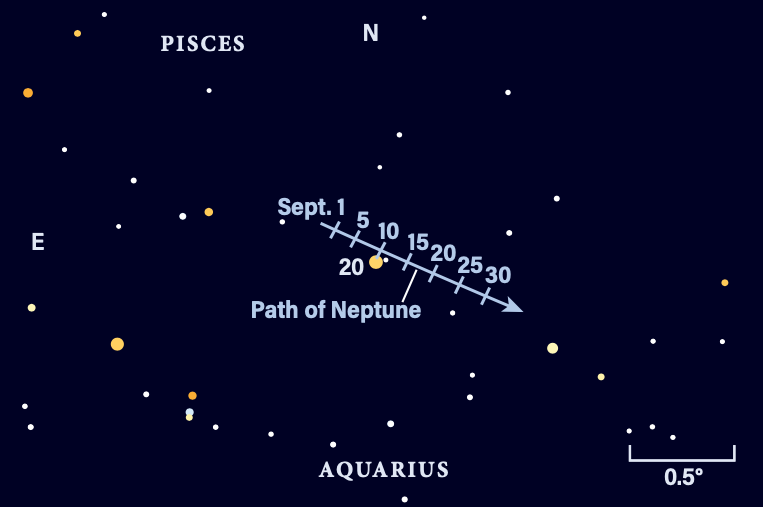

This is the best month of the year to spot Neptune. It has a fine appulse with 5th-magnitude 20 Piscium shortly before reaching opposition, which makes spotting the magnitude 7.7 world much easier.

On Sept. 1, grab a pair of binoculars to find Neptune 16′ northeast of the star. Watch each night as Neptune moves southwestward, reaching a point 4′ due north of 20 Psc on Sept. 10. The star itself is a binary with 10″ separation, while a 10th-magnitude star stands 3′ to its west.

Neptune reaches opposition Sept. 19, now 13′ west of 20 Psc. The distant planet lies 28.9 AU from Earth. Through a telescope, Neptune spans 2″ and glows with a bluish hue. By the end of September, the planet is 31′ southwest of 20 Psc.

Jupiter rises around 10 p.m. in early September and stands 20° high in the east at the same time on Sept. 30. It starts the month at magnitude –2.6 — an unmistakable object in the faint constellation Aries. The best views of the giant planet are in the early-morning hours, when Jupiter stands more than 60° high in the southern sky.

Binoculars will reveal some of its moons as well as the 6th-magnitude star Sigma (σ) Arietis. The star stands due north of Jupiter on the 18th.

Jupiter is a favorite of observers because of the wealth of detail in its atmosphere: dark equatorial belts, the Great Red Spot, and an ever-changing view as new features regularly appear, given its fast rotation period of less than 10 hours.

The Galilean moons orbit with periods from about two to 17 days. When they pass in front of Jupiter, they cast their shadows on the cloud tops. Io undergoes regular transits across Jupiter’s disk. Events occur overnight on Sept. 3/4, 12/13, 19/20, and 26/27. The shadow of Io is first to appear, followed by the moon. In early September the moon trails its shadow by 74 minutes; this shrinks to 54 minutes by the 26th, due to the changing relative position of Earth with respect to Jupiter and the Sun.

Ganymede, Jupiter’s largest moon, casts its big shadow on the planet’s southern polar regions Sept. 6/7, starting at 1:51 a.m. EDT on the 7th (still the 6th in western time zones) and ending 3:40 a.m. EDT. The following night (Sept. 7/8), Europa’s shadow transits Jupiter, beginning at 12:30 a.m. EDT on the 8th. The event is already underway for the western U.S. as Jupiter rises. The shadow exits the disk at 2:49 a.m. EDT. Europa begins a transit eight minutes after its shadow leaves.

Ganymede also undergoes an occultation behind the planet’s northern limb Sept. 17/18. This is best viewed from the eastern half of U.S. due to its lower altitude in the west. Ganymede disappears slowly due to the shallow angle of the limb near the pole. It begins at 12:28 a.m. EDT on Sept. 18 (note this is still late on the 17th in the Central time zone), but you’ll see the moon blend with the limb of Jupiter a bit earlier. It reappears at 1:22 a.m. EDT.

Uranus stands about 8.5° southwest of the Pleiades star cluster (M45) and 7.5° northeast of Jupiter. With binoculars, scan southeast of M45 until you come across an arc-shaped trio of 5th-magnitude stars led by Tau (τ) Arietis. Drop 3° south of this grouping to find Uranus. It glows at magnitude 5.7.

Uranus has started its retrograde path westward. It moves slowly early in the month and picks up the pace later. During September it moves less than 0.5°. While you’ve got Jupiter in your telescope, remember to swing east just a few degrees to view this distant planet. Its greenish-hued, 4″-wide disk is evocative, standing just over 19 AU from Earth. When William Herschel spotted it in 1781, it was the first planet ever discovered with a telescope.

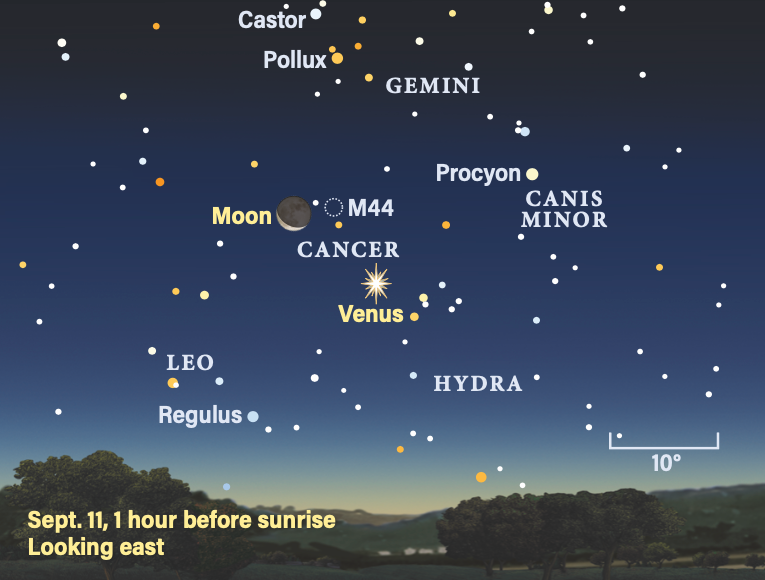

Venus dominates the morning sky, shining brilliantly in the hour before dawn. On Sept. 1 it is magnitude –4.6; it brightens to its greatest brilliancy of –4.8 by the 9th. Venus rises on Sept. 1 just before 5 a.m. local daylight time, around the same time astronomical twilight begins. The planet is in southern Cancer, hanging more than 20° below Castor and Pollux, the brightest stars in Gemini.

On Sept. 11, a lovely crescent Moon hangs 11° due north of Venus. Scan the sky around them with binoculars to catch a view of M44, the Beehive Cluster, about 4° southwest of the Moon.

On the 1st, a telescope shows Venus’ 50″-wide crescent is 11 percent lit. By the 11th, it’s a 21-percent-lit crescent spanning 43″ — a product of its increasing distance from Earth and growing angular separation from the Sun. The planet continues shrinking, reaching 32″ on the 30th, while its crescent is 36 percent lit. Venus crosses into Leo Sept. 25 and ends the month 7.8° west of Regulus, the Lion’s brightest star.

The best morning view of Mercury in 2023 occurs this month. The tiny planet hops into the morning sky after its Sept. 6 inferior conjunction. It’s already magnitude 1 by the 16th, standing 8° below Regulus. Brightening quickly, it’s magnitude 0 four days later on the 20th, rising 90 minutes before the Sun. It reaches greatest western elongation of 18° on the 22nd, shining at magnitude –0.3. Mercury continues to brighten, reaching magnitude –1 on the 29th. The world is a dramatic object 9° high 30 minutes before sunrise as Venus, high above, watches over it.

Sept. 23 marks the autumnal equinox (2:50 a.m. EDT), when the Sun appears above the celestial equator, moving southward.

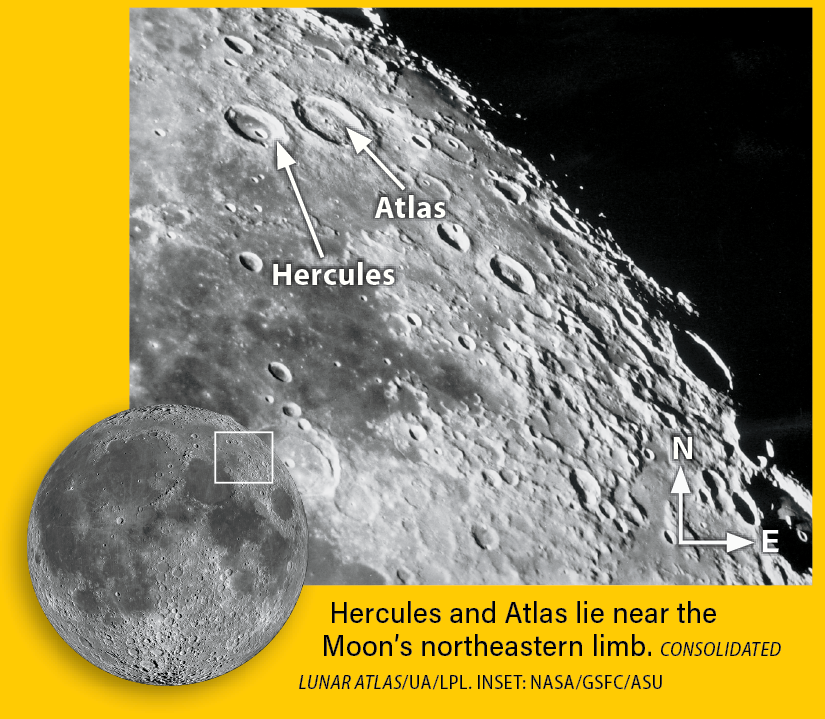

Rising Moon: Mythological muscle men

You can use the Harvest Moon effect twice this month. After Full phase, the waning gibbous Moon still rises in the early evening. Without having to stay up late, it’s a splendid opportunity to see reversed light on Luna. Here on Earth, the play of light and shadows in your neighborhood is different at sunrise and sunset; likewise on the Moon. It’s not simply the same scene running backward in time!

Look to the northern third of our satellite on the evening of the 2nd and 3rd (both this month and next) to see the neatly paired muscle men of mythology, Atlas and Hercules. Atlas is closer to the limb. Hercules, 43 miles across, sports a floor of lava punctured by a sharp-edged crater of more modest size. The older Atlas has wrinkles and a jumble of central peaks typical of larger craters. At sunset on the 3rd, Atlas’ central features drop into darkness, while Hercules’ inner crater will soon succumb to shadow, but hasn’t yet.

Under “normal” (waxing) lighting just after midmonth, the pair are emerging into sunlight and their shadows appear reversed: The outer rims are lit on the eastern side, while the inner crater walls are now lit to the west. On the 18th, the dynamic duo makes quite the standout feature on the crescent. If you get a streak of good weather, see if you can notice night by night how the lava seems to get darker and produce better contrast. At sunrise or sunset, all surfaces scatter light in a similar fashion, but at higher Sun angles, the differences become striking.

Meteor Watch: Ecliptic glow

There are no major meteor showers in September. As the bright planets beckon early-morning observers, be on the lookout for the zodiacal light in the predawn sky. It’s visible only from very dark locations. The distinctive cone-shaped brightening lights up the steeply inclined ecliptic with a glow similar to that of the Milky Way. It extends from Leo through Cancer and into Gemini. This glow is from meteoritic dust that pervades the inner solar system.

Watch for the zodiacal light in the third week of September around New Moon. Venus will be embedded in the faint light and can help guide your eye along the ecliptic. Watch for Mercury rising later as well. Twilight will be a lower, wider glow along the eastern horizon that quickly drowns out the zodiacal light.

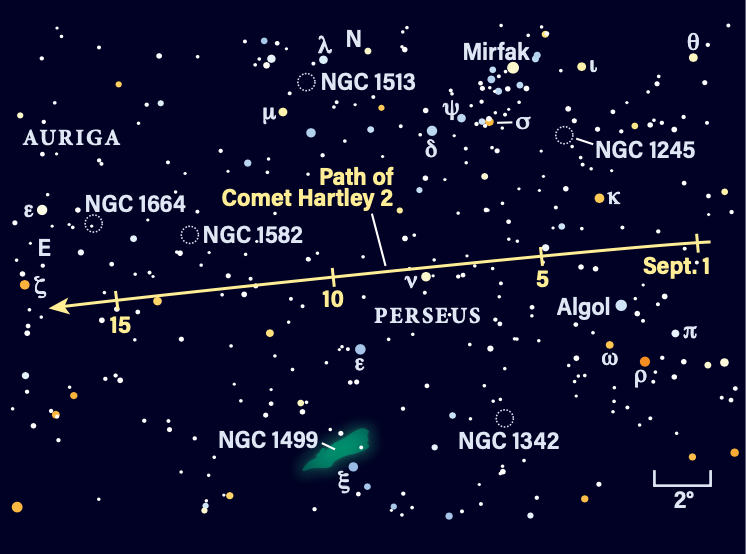

Comet Search: Reliable returner

Initiating a year-long feast of comets brighter than 10th magnitude is 103P/Hartley (Hartley 2). Get under some dark skies with at least a 4-inch scope throughout this apparition as it is unlikely to break 8th magnitude, coming closest to Earth Sept. 25/26. Wait until late evening for the comet to climb up in the northeast.

Imagers should try a 135mm lens to frame the green glow with the California Nebula (NGC 1499) before the second week of the month, and Auriga’s Messier clusters and Flame Nebula (IC 405) during the third. Few photos from two orbits ago show a white dust tail, though we know that Hartley puts out dust — dramatically revealed by a spacecraft visit in 2010.

Readers in the southern U.S. can glimpse C/2021 T4 (Lemmon) masquerading as a ghost of Zubenelgenubi from the 9th to the 14th right as evening twilight fades. If you want to get the periodic 2P/Encke on your lifetime list, the New Moon weekend of the 16th and 17th is a must while it is up near Castor. Otherwise, Encke quickly drops into morning twilight and our next decent view is more than a decade away. From Sept. 23 to 25, it skirts 3° north of Leo’s big spiral galaxy NGC 2903.

Locating Asteroids: Between the rings

Aquarius is a bit tough to see from the suburbs. Set your sights on Saturn in the southeast and drop 7° — about a finder field — to land close to main-belt asteroid 8 Flora.

Start a little more south of Saturn, using the 5th-magnitude star Upsilon (υ) Aquarii as an anchor. Take along a nebula filter to catch the rather large, famous smoke ring of the Helix Nebula (NGC 7293).

The somewhat-sparse star fields here can be helpful for checking position and orientation, since their patterns won’t be confused by hordes of background suns. Measuring a respectable 90 miles across, 8th-magnitude Flora forms a nearly straight line with a pair of brighter and fainter widely separated stars from the 7th to the 9th. Mid-month, Flora scootches past a small, hockey-stick-shaped asterism, making it super easy in both cases to make a field drawing in a logbook to plot its passage.

Wait past 10 p.m. for Flora to climb above rooftops and trees, and give it a rest when the Moon is nearby from the 25th to the 27th.