Walk out any September evening an hour after sunset and you’ll find two planets already up in the southern sky. Jupiter is the brightest, nearly 30° above the southern horizon. Saturn lies to its east (left). They’re situated in eastern Sagittarius, and observers at dark sites have a spectacular view of the Milky Way along with these planets.

Before we turn to this bright pair, let’s first get a glimpse of Mercury. It’s difficult to spot as it approaches its greatest eastern elongation October 1, as the ecliptic lies so low to the horizon that it’s not too favorable.

On September 21 and 22, Mercury passes close to Spica, Virgo’s brightest star. The pair will be difficult to see due to bright twilight. They’re side by side September 21, standing 0.7° apart. Spica shines at magnitude 1 and Mercury is magnitude 0. Try spotting them 20 minutes after sunset, when the pair are 5° high. Ten minutes later, they’re only 3° high and the sky is darkening. They set 20 minutes later. On September 30, Mercury sets 50 minutes after the Sun. There’s a slim window to catch it.

Let’s look at Jupiter first. It wanders westward until September 13, when it halts at its stationary point and returns to direct motion, shaving off a degree in the gap between itself and Saturn by the end of the month. The ringed planet reaches its stationary point two weeks later, on the 29th.

Jupiter’s disk spans 44″ and presents a wealth of detail. Two dark equatorial belts are most obvious, and more delicate structures lie between them and at higher latitudes. The dusky features are best seen during moments of steady seeing, when patience will provide the reward of a stunning view. Occasionally, the Great Red Spot makes a commanding appearance, scooting across the disk in a matter of hours.

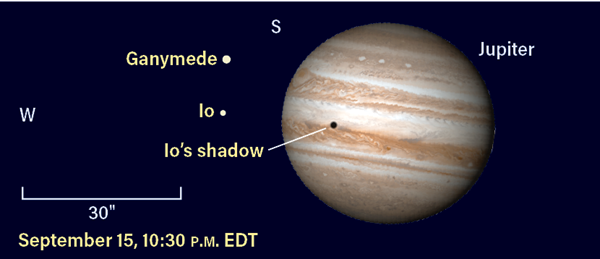

Your scope will also show the four famed Galilean moons, first spotted in 1610. Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto orbit the planet every 1.8, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. The inner three moons are in a 4:2:1 orbital resonance, meaning every few days they return to approximately the same location relative to Jupiter. And all four moons undergo eclipses, transits, and occultations. Here are a few examples this month to watch for; note there are more than just those listed here during the month.

Io and Ganymede pass each other on September 15. From the Midwest and eastern U.S., Io and its shadow are already transiting Jupiter as darkness falls. Io leaves the disk at 9:51 P.M. EDT and wanders west, while Ganymede heads the other way. The pair is closest (10″) around 10:30 P.M. EDT, then Ganymede continues toward the planet’s limb. Io’s shadow leaves Jupiter at 11:03 P.M. EDT and Ganymede is occulted by the planet starting at 11:43 P.M. EDT.

On September 30, Callisto’s shadow begins creeping onto Jupiter starting at 9:04 P.M. EDT; it takes 10 minutes to fully appear. How soon do you notice it on the northeastern limb? Io reappears from eclipse 22″ off the eastern limb of the planet at 12:03 A.M. EDT on October 1, while Callisto’s shadow continues across Jupiter’s disk.

You’ll find 8th-magnitude Titan, Saturn’s brightest moon, due north of Saturn on September 1 and 17 and due south on September 9 and 25. Visible in small scopes are Tethys, Dione, and Rhea, all roughly 10th magnitude. Their relative positions change over a few hours. Twelfth-magnitude Enceladus is near the bright edge of Ring A, where it can be lost in ring’s brilliance, so you’ll need to look carefully.

Iapetus reaches superior conjunction September 7, when it lies 63″ due north of Saturn near magnitude 11. The moon’s two-toned surface causes its magnitude to vary from 10.5 down to 11.7 as it orbits the planet. At superior conjunction, 50 percent of each hemisphere faces Earth. The moon continues toward eastern elongation, reaching it September 25.

Neptune reaches opposition on September 11 in Aquarius. It rises with a Full Moon in the east soon after sunset on September 1. Binoculars will show the magnitude 7.9 planet near 4th-magnitude Phi (φ) Aquarii. Scan 2.5° east of the star to find Neptune, where it forms a triangle with a pair of 6th-magnitude field stars. Neptune lies midway between them on September 30, now only 1.5° east of Phi. A telescope reveals its bluish disk, spanning 2.3″.

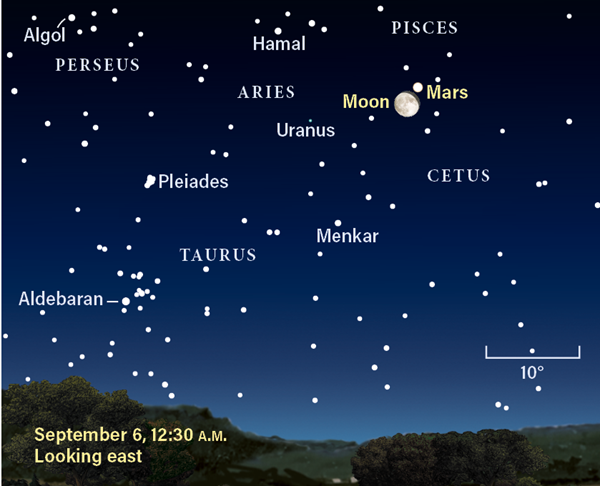

Peak Mars observing season begins in earnest as we near next month’s opposition. The Red Planet is less than half an astronomical unit from Earth and its disk spans 19″. (One astronomical unit is the average Earth-Sun distance.) Mars’ apparent size will grow to 22″ by the end of September, just 1″ shy of its diameter at opposition. It’s located in Pisces,

nestled in the V of this faint constellation. The planet’s eastward drift slows to a halt September 9, after which it begins a retrograde loop, tracking quickly west. Starting the month at magnitude –1.9, its orange glow is unmistakable in a region devoid of bright stars. It brightens to –2.4 this month — comparable to Jupiter.

A bright waning gibbous Moon lies 1.5 Moon-widths south of Mars on September 5. The same night, our satellite occults the Red Planet, visible from Central and South America, North Africa, and southern Europe.

Telescopes will show the disk 92 percent lit on September 1 and almost fully illuminated (99 percent) by the end of the month. Major features visible on the martian disk at 2 A.M. local time in early September include Syrtis Major and the bright Hellas basin. Watch for brightening in some regions that could be indicative of the onset of a dust storm.

In the second week of September, the dark Mare Sirenum and Mare Cimmerium span the martian disk. They’re followed in mid-September by the brighter volcanic Tharsis Ridge and Olympus Mons near the terminator. Also watch for bright features along the terminator that could be clouds. By September 21, the Mariner Valley rotates onto the disk. The dramatic features of Sinus Sabaeus and Sinus Meridiani appear during the last week of the month.

Uranus lies 13° east of Mars on September 1. If you have a go-to mount, it’s easy to find. But there are no bright stars in the region, so star-hoppers have a challenge. After midnight — once Uranus reaches a decent altitude in the eastern sky — scan with your favorite binoculars between Hamal (Alpha [α] Arietis), Aries’ brightest star, and Menkar (Alpha Ceti) in Cetus. The two are 23.5° apart; Uranus lies between them just under 11° from Hamal and shines at magnitude 5.7. The 6th-magnitude star 29 Arietis lies near the planet. The ice giant is 0.6° southwest of the star on September 1; the gap widens to just over 1° by September 30. Uranus’ greenish disk is visible in a telescope. High magnification reveals a 3.5″-wide disk.

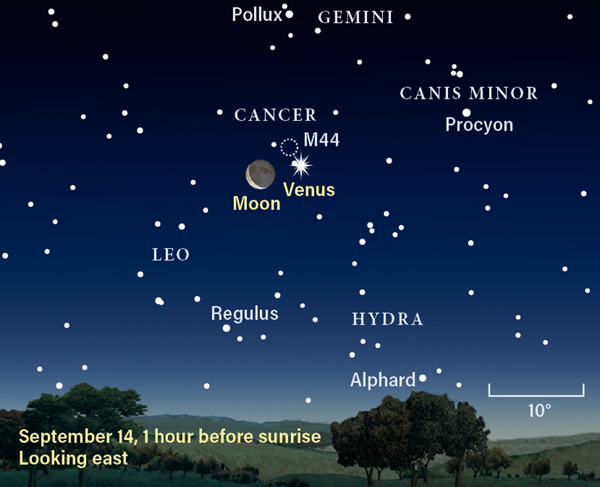

Venus rises around 3 A.M. local time on September 1, located south of the bright stars Castor and Pollux in Gemini the Twins. Shining at magnitude –4.3, it’s unmistakable. A telescope reveals a gibbous phase of 60 percent in early September, which grows to 71 percent by the end of the month. Venus is receding from Earth and consequently its disk shrinks from 19″ to 16″ over the same period.

A spectacular scene occurs on September 14, when Venus lies 2.5° south of the Beehive Cluster (M44) in Cancer the Crab. A waning crescent Moon floats nearby, only 5° from both Venus and M44.

Venus crosses into Leo in late September. The planet ends the month 3° west of Regulus, Leo’s 1st-magnitude alpha star, located at the base of the sickle asterism.

Rising Moon: Beyond the edge

There’s something uncommon going on this month. Starting on the 19th, look at all that terrain between Mare Crisium and the limb! Mare Marginis and Mare Smythii are huge splotches of dark instead of thin channels. This is about the best perspective of the eastern zone you can get — thanks to lunar libration, we see “around” the side of the Moon a bit more than we access with our normal face-on view.

The two large dark zones are huge ponds of lava that welled up from below and froze billions of years ago.

The northern one is Marginis, literally the “sea at the margin,” while the southern one is Smythii, honoring British amateur astronomer William Henry Smyth. The white wall on the limb beyond Smythii is made up of a series of crater rims, the largest being Hirayama, Purkyne, and Babcock. Is the libration enough for us to see inside them? Fire up the magnification and take a look.

In between the maria is the prominent crater Neper, with its lava-filled basin and notable central mountains. Beyond it lies the smaller Jansky and, if you can see one more, Jansky F at longitude 92 east. On the northern flank of Marginis, the rugged walls of Goddard ring a flat lake of lava that flooded higher than the crater’s peak. For a few evenings, the lumpy rim of Al-Biruni should poke up from the limb just beyond Goddard. Observe these and you’re on your way to becoming a veteran selenophile.

Each night after First Quarter, the combined lunar orbit and spin gives the impression that this eastern flank of the Moon is rolling away from us. Watch for Goddard’s rim and Neper’s peak to stick up off the limb when they are in profile. September 26 is this year’s International Observe the Moon Night; an 80-percent-lit Moon will be up all evening, a great time to try to spot the effects of libration for yourself.

By the time we get to Full, all of the features past Crisium will have spun beyond the limb. The sequence repeats the next couple of months, but less prominently.

Meteor Watch: Dust on display

Meteor rates wane after their August peak. There are no major showers in September. The background or sporadic rate of about seven meteors per hour continues, and you might even be lucky to catch an errant fireball.

If you’re up observing Mars in the early hours — say between 4:30 and 5:30 A.M. local time — be on the lookout for the zodiacal light. This cone-shaped brightening occurs along the steeply inclined ecliptic, extending from Leo through Cancer and into Gemini before twilight. Venus will be embedded in the middle of the faint light. You’ll need moonless conditions, which occur in the last two weeks of the month. Higher-altitude observing sites improve your chances of viewing the zodiacal light, which is a persistent faint glow from meteoritic dust that pervades the solar system.

Comet Search: Come again?

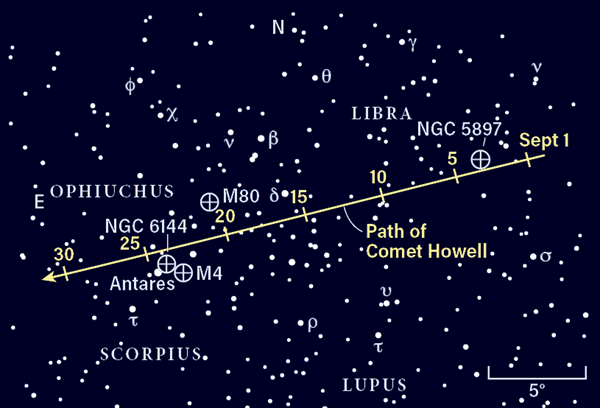

With a short period of 5.5 years, Comet 88P/Howell has returned to keep us company through early winter. You may not remember its name because that extra half-year placed Earth on the other side of the solar system during its last passage. Only every 11 years are we in a good position to view it.

The comet’s closest approach to the Sun occurs on the 26th, and it should glow around 9th magnitude all month. A green halo will be easy to capture for a small telephoto lens on a tracking mount. Under country skies, a 4-inch scope will visually pick up this small gray fuzz.

On September 4 and 5, Howell shares a medium-power field with the loose globular cluster NGC 5897 in Libra. Leverage the brief period of darkness at dusk before moonrise. Much better will be the nights of September 22 through 25, when Howell threads the gap between Messier globulars 4 and 80, nestled close to brilliant Antares. Unfortunately for the “comet ferret” Charles Messier, his scope was just a bit too small, leaving the comet’s discovery to Ellen Howell from Palomar Mountain in 1981.

Locating Asteroids: Nothing fishy about it

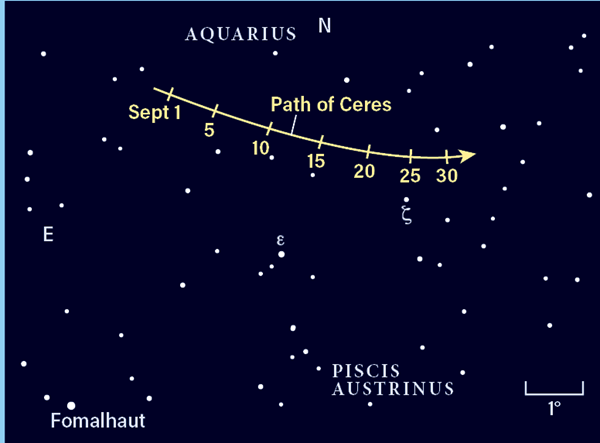

The good times for asteroid tracking are back with the rise of dwarf planet 1 Ceres to binocular visibility. All this month it slides one field of view above the yellow luminary Fomalhaut, plying the southern sky after dusk. Unless you live in the southern U.S., where Piscis Austrinus gets high enough, you’ll need those binoculars to trace out the rest of the constellation, whose second-brightest star is magnitude 4.3.

Wait until late evening for Ceres to climb above the horizon’s haze, then nudge your view upward to its path. Our line of sight is far from the Milky Way’s central bulge, so we won’t be bothered by a forest of background stars, as in previous months. In fact, at magnitude 7.7, Ceres will be one of the brightest dots in the eyepiece of a telescope. Find a notable pattern of at least three stars, plop them into your logbook, and come back a night or two later to confirm which one shifted. Avoid the nights of the 1st and 28th, when the Harvest Moon skims to the north.

By coincidence, Ceres just hit its least bright opposition on August 28, lying at the distant end of its egg-shaped orbit when we passed by. Because the next “farthest close approach” will occur in 2043, Ceres will get easier for many observing windows to come.