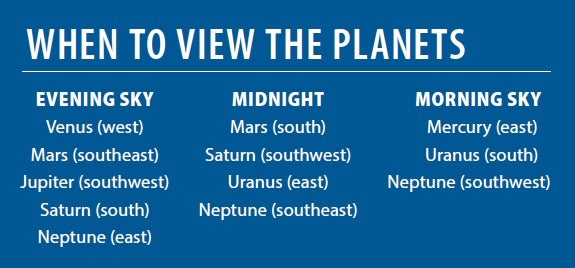

Your first target these September evenings should be Venus. Earth’s inner neighbor lies low in the west-southwest shortly after the Sun goes down. From mid-northern latitudes on the 1st, it appears about 10° high a half-hour after sunset. Despite its low altitude, it’s easy to see because it shines brilliantly at magnitude –4.6. Use binoculars and you’ll see Virgo’s brightest star, magnitude 1.0 Spica, 1.3° to the planet’s upper right.

Although Venus dips a hair lower each evening, it also grows brighter. It peaks at greatest brilliancy September 21, when it gleams at magnitude –4.8. It then stands just 5° high in the southwest 30 minutes after sunset, however, so you’ll need an unobstructed horizon to get a good view.

Viewing Venus through a telescope in September reveals remarkable changes. On the 1st, the planet appears 30″ across and 40 percent lit. By the 15th, it spans 36″ but the Sun illuminates only 30 percent of its Earth-facing hemisphere. And on September’s final evening, Venus shows a disk 46″ in diameter and 17 percent lit.

You can find Jupiter blazing in the southwest after sunset all month. It lies 23° to Venus’ upper left September 1; the gap closes to 14° by the end of the month. Be sure to watch when the waxing crescent Moon slides past these planets. On September 12, our satellite lies 9° above Venus and 16° right of Jupiter. By the next evening, the Moon stands 4° to Jupiter’s upper right. Although the magnitude –1.9 giant planet appears less than one-tenth as bright as Venus, it easily outshines every nighttime star.

If you want crisp views of Jupiter through a telescope, observe in late twilight before the planet sinks too close to the horizon. Low altitudes mean its light has to travel through more of Earth’s image-distorting atmosphere, which washes out fine detail. For the same reason, views in early September should be sharper than those later on.

Small instruments also reveal Jupiter’s four big moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. The satellites shift positions noticeably within an hour or two, and will look completely different from one night to the next. The illustration on the right side of p. 41 will help you identify which moon is which.

Scan some 45° east of Jupiter, and your eyes will land on Saturn nestled among the background stars of northern Sagittarius. The magnitude 0.4 ringed planet lies due south and at peak altitude an hour after sunset September 1. Once the sky grows dark, you’ll notice it is set against some of the Milky Way’s richest regions. Binoculars reveal Saturn as a yellow sapphire with the misty glows of the Trifid Nebula (M20) 1.7° to the west and the Lagoon Nebula (M8) 2.2° to the southwest.

A First Quarter Moon interrupts the deep-sky viewing when it passes by September 16 and 17. Saturn’s easterly motion against the starry background during September’s second half carries it to a spot 2.2° east of M20 by month’s end.

While binocular views of Saturn are thrilling, they can’t match the extraordinary sight of the ringed planet through a telescope. Any scope shows the gas giant’s 17″-diameter disk surrounded by stunning rings that span 38″ and tip 27° to our line of sight, their maximum tilt of the year. Under good seeing conditions, you can spot the A ring poking above the planet’s north pole behind Saturn. Also look for the planet’s shadow falling on the eastern side of the rings.

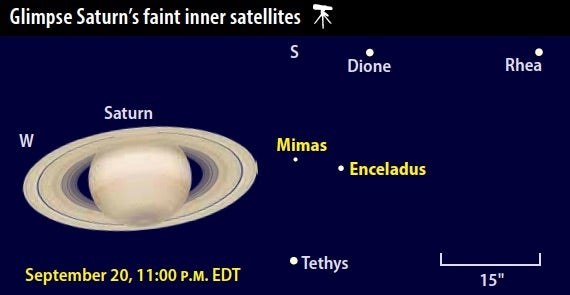

The smallest instruments also reveal Saturn’s largest moon, 8th-magnitude Titan. A 4-inch scope brings in four 10th-magnitude satellites. Tethys, Dione, and Rhea, which orbit Saturn at less than half Titan’s distance, are the easiest targets. And with periods ranging from 1.9 to 4.5 days, these three provide a constantly changing show.

Two inner moons — 12th-magnitude Enceladus and 13th-magnitude Mimas — show up through 8-inch scopes when they lie farthest from Saturn. Try to find them September 20, when they reach greatest eastern elongation within an hour of each other. The two stand just beyond the rings’ edge halfway between Dione and Tethys.

The fourth naked-eye evening planet lies in the south-southeast after sunset. Mars shines at magnitude –2.1 September 1, making it the second brightest of our planetary quartet, but it stands out just as much for its stunning orange color. The Red Planet then sits on the border between Sagittarius and Capricornus. Binoculars reveal globular star cluster M75 just 4° to its north.

As September progresses, Mars treks northeastward against the Sea Goat’s background stars. It also retreats from Earth and, as a result, its diameter shrinks from 21″ to 16″ during the month, and it fades about 0.2 magnitude per week. The best times to view it through a telescope come when it lies due south and at peak altitude. In early September, this occurs around 10:30 p.m. local daylight time. Late in the month, it appears highest at 9 p.m.

During moments of good seeing, Mars resolves into a patchwork of dark and bright markings. From North America, evening views in early September show the dark region Mare Sirenum on the central meridian, the line joining the planet’s north and south poles that passes through the center of the disk. By the end of the first week, the dark feature Solis Lacus takes center stage. At the same time, Olympus Mons appears on the planet’s morning terminator. This is the time to watch for bright clouds that often appear around this huge volcano. In September’s second week, the dark sands of Mare Erythraeum take center stage.

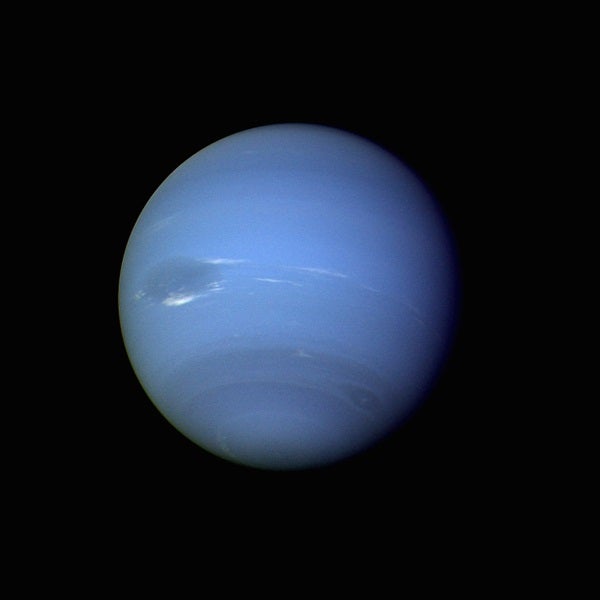

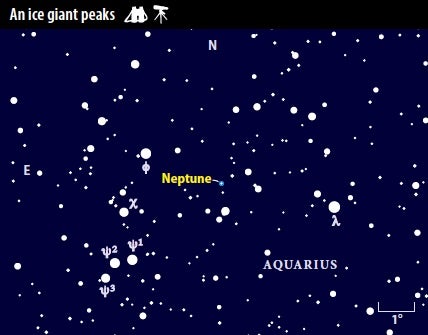

Once you’ve viewed the bright evening planets, turn your attention to their fainter siblings. Neptune reaches the peak of its yearly appearance when it comes to opposition September 7. It then lies opposite the Sun in our sky, rising at sunset and climbing halfway to the zenith in the southern sky around 1 a.m. local daylight time.

Neptune glows at magnitude 7.8, so you’ll need binoculars or a telescope to see it. It lies 2.2° west-southwest of 4th-magnitude Phi (ϕ) Aquarii on September 1 and 2.9° away from this star on the 30th. A telescope at medium magnification reveals the planet’s 2.4″-diameter disk and blue-gray color.

Uranus rises around 9:30 p.m. local daylight time as September begins, and some two hours earlier by month’s close. It stands well clear of the eastern horizon just a couple of hours later. The ice giant world resides in southwestern Aries, 12° south of the Ram’s brightest star, 2nd-magnitude Alpha (α) Arietis.

At magnitude 5.7, Uranus appears bright enough to see with the naked eye from a dark site, though binoculars make the task easier. Only a few background stars in the area glow as brightly as the planet. To confirm a sighting, point your telescope at the suspected planet. Only Uranus shows a disk, which spans 3.7″, with a distinctive blue-green color.

As dawn approaches in early September, Mercury appears low in the east. The innermost planet rises nearly 90 minutes before the Sun on September 1 and stands 10° high a half-hour before sunup. It shines at magnitude –0.8 and should be easy to spot against the twilight glow. A telescope reveals the planet’s 6″-diameter disk, which appears two-thirds lit.

Mercury drops lower with each passing day but grows brighter as it descends. Look for it through binoculars September 5 and 6, when it passes within 1.5° of 1st-magnitude Regulus. The pair lies about 7° high 30 minutes before sunrise.

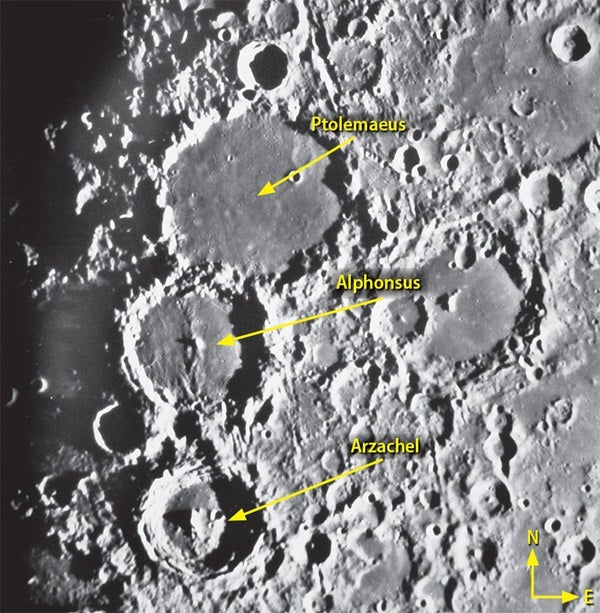

Intriguing features abound on a waxing gibbous Moon. Marvel at Tycho’s satellite-spanning rays, expansive Mare Imbrium with striking Sinus Iridum on its northwestern edge, and the prominent crater Copernicus with its intricate debris splatter.

Consider starting your observing session before darkness falls, when the light-blue sky reduces the glare of the Moon’s bright disk. Sometimes, the Moon at night is simply too bright through a telescope. A filter helps, but sunglasses provide a nice low-tech solution.

Target the Moon the evening of September 19, when Mars hangs some 5° below it. The sunrise line has moved past the fascinating crater Gassendi, which perches on the northern edge of Mare Humorum (Sea of Moisture) in the lunar southwest. Circular Gassendi spans 69 miles and tilts down toward the center of Mare Humorum.

Gassendi displays multiple peaks and slumped walls, a characteristic of many large craters. You can even see that the prominent crater on its northern rim formed after the main event and pushed this material inward. The arcs and rilles visible in the southern and southeastern parts of Gassendi are remnants of fracturing. Up and down motions of the crust caused surface cracks similar to those you might see in a pie crust. Lava later welled up from below and covered half of the crater’s floor.

Scientists named this crater after 17th-century French astronomer Pierre Gassendi. In 1631, he became the first person to observe Mercury transiting the Sun.

No major meteor showers occur in September, and the minor ones produce no more than five meteors per hour. But the tiny dust particles that give rise to meteors when they get incinerated in our atmosphere show up in a different way this month. Dusty debris from asteroid collisions and ancient comets fills the inner solar system. The particles concentrate along the orbital plane of the planets, called the ecliptic. And when the ecliptic angles steeply to the eastern horizon before dawn, as it does in September, the dust appears to the naked eye as a cone-shaped glow.

To see this zodiacal light, or false dawn, you must observe from a dark site when the Moon is out of the morning sky (September 8–23 this year). It appears most conspicuously within a half-hour of twilight’s first glow.

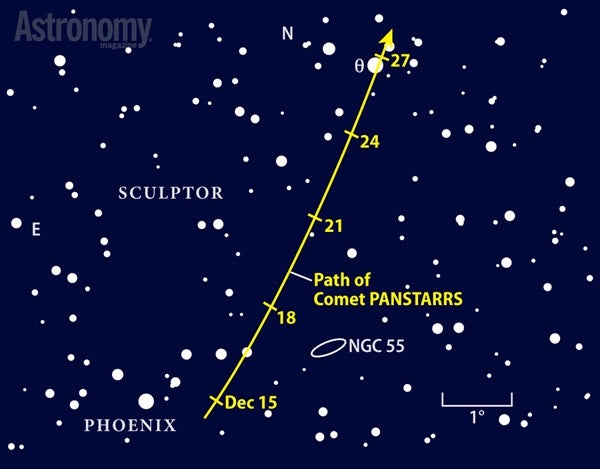

Since its discovery in 1900, Comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner has returned to the inner solar system every 6.6 years. Some visits are better than others, however. The comet makes its closest approach to both the Sun and Earth during September’s second week, which should push this performance to its second best ever.

Astronomers expect 21P to peak at 6th or 7th magnitude. But the comet’s proximity to Earth means that it will be a diffuse, low-surface-brightness object, so you’ll want to view it from a dark-sky site. Although its host constellation, Auriga, rises in the evening, wait until it climbs high in the sky before dawn.

Start at low power to capture the entire coma and most of its bluish gas tail, which should extend 1° or more to the west. Push your scope around a bit to activate the motion-sensitive rods of your eye’s peripheral vision. Then try medium magnification to see more detail. The coma’s eastern side, where the solar wind pushes ionized gas away, should appear sharpest.

Giacobini-Zinner lies within 2° of magnitude 0.1 Capella on September 2 and 3. Imagers will want to target it a week later at New Moon, when it passes through a photogenic region of the winter Milky Way that includes the star clusters M36 and M38.

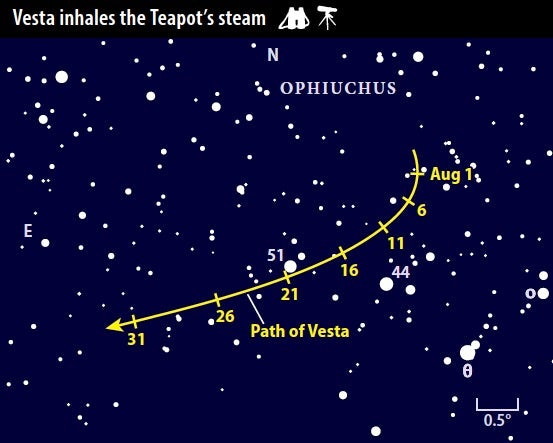

September’s typically great weather likely will give you a string of clear nights to follow asteroid 4 Vesta passing near the Milky Way’s center in Sagittarius. From the suburbs, start at the yellow beacon Saturn and make the short hop to this main belt asteroid. Under a dark sky, begin at the sprawling Lagoon Nebula (M8) and shift to the position indicated on the chart below.

No matter your observing site, the first thing you’ll notice in early September is the scarcity of background stars, which allows Vesta to stand out a bit more. Interstellar dust in our galaxy’s disk obscures much of our view. Until mid-September, 7th-magnitude Vesta is the brightest object in the field.

Once the asteroid passes south of the Lagoon around the 21st, you might confuse several stars for the space rock. Make a sketch of the field that includes the four or five brightest dots, then return a night or two later to confirm which “star” moved. You can also take advantage of Vesta’s proximity to track down globular star clusters NGC 6544 and NGC 6553. Through a 6-inch scope, they’ll look like slightly fuzzy, 8th-magnitude stars.