Let’s kick off our tour with one of the month’s more challenging planets. Saturn lies low in the southwest during evening twilight in early December. The magnitude 0.5 world appears as a lonely point of light in the gathering darkness. On the 1st, it stands about 10° high 45 minutes after sunset. A week later, on the 8th, it’s only 7° high at the same time. But a slender, two-day-old Moon accompanies it that evening. They lie 3° apart and appear beautiful through binoculars. The ringed planet succumbs to bright twilight within a week. It will pass on the far side of the Sun from our viewpoint at the beginning of January.

While twilight partially obscures Saturn in early December, Mars appears conspicuous in the southern sky. The Red Planet shines at magnitude 0.0 and dominates the background stars of its host constellation, Aquarius. As darkness falls, the ruddy object lies halfway to the zenith — nearly double its peak altitude at opposition this past summer.

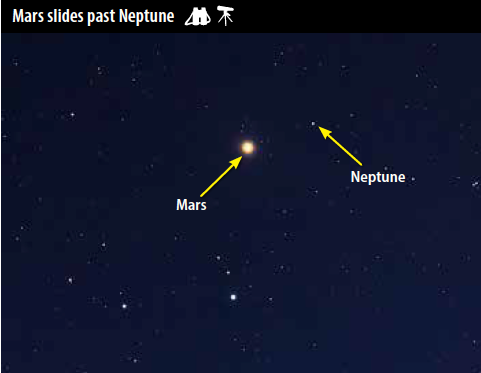

As you gaze at Mars with your naked eye, you might assume it’s the only object of interest in Aquarius. But target the planet through binoculars and you can pick up the much fainter glow of Neptune. The distant ice giant lies 3.6° east-northeast of Mars on the evening of the 1st. Although both worlds move eastward relative to the starry backdrop, Mars moves much faster. The distance between the two drops by about 0.6° every day.

A quick calculation shows that the two should be nearly on top of each other within a week, and mathematics once again reveals its power. On the North American evening of December 6, Neptune lies 23′ east-northeast of Mars. The two switch positions the following evening, with Neptune 16′ southwest of Mars. (The magnitude 6.1 star 81 Aquarii stands 12′ north of Mars.) Although you’ll need binoculars or a telescope to spot magnitude 7.9 Neptune, you’ll rarely get a better guide than you’ll have these two nights.

This is the second close conjunction between these planets in a couple of years. On December 31, 2016, the two appeared slightly nearer to each other, though this month’s event occurs higher in a dark sky. The future isn’t as bright, however. You’ll have to wait nearly two centuries, until October 19, 2210, for Mars and Neptune to pass closer under a dark sky.

Although the worlds appear together these December evenings, Neptune lies 28 times farther from Earth. The ice giant’s large size only partially compensates for its greater distance. When viewed through a telescope, Neptune appears 2.3″ across while Mars spans 9″.

You won’t see any detail on Neptune beyond its blue-gray color. Mars is a different story. Sunlight illuminates 86 percent of its Earth-facing hemisphere, so its disk appears distinctly gibbous. And most scopes should reveal one or two dark markings.

Following the conjunction, Mars’ eastward motion carries it within 0.3° of 4th-magnitude Phi (ϕ) Aqr on December 12. A First Quarter Moon passes 4° south of the planet on the 14th. Mars crosses the invisible border between Aquarius and Pisces on the 21st and ends the year a few degrees southeast of the latter constellation’s Circlet asterism. The Red Planet then glows at magnitude 0.5 and sets shortly before midnight local time.

Slow-moving Neptune remains in Aquarius through the end of the year. On Christmas Eve, it passes 15′ due south of 81 Aqr. This star serves as a useful guide in the second half of December after Mars has moved on.

The challenge comes in finding the right area — there are no bright stars nearby to guide you. Start at 3rd-magnitude Beta (β) Arietis, which lies near the center of the Star Dome map on p. 38–39. Then move 12° due south and slightly west to locate 4th-magnitude Omicron (ο) Piscium. Uranus stands 1.6° north-northeast of this star in early December and moves to a point 1.3° almost due north by month’s end.

A telescope reveals the planet’s 3.7″-diameter disk and striking blue-green color. You can be forgiven for thinking Uranus has gained a moon the night of December 24/25 when a 9th-magnitude field star slides 1′ to its south. Try to view the ice giant during the early evening hours when it peaks some 60° above the southern horizon.

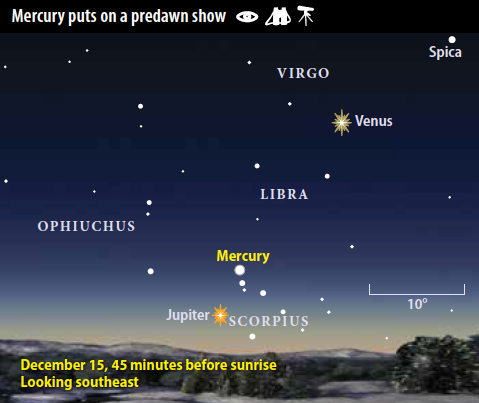

Although the evening sky has its charms, the morning sky offers December’s three brightest planets. Even in this dazzling company, Venus stands out. The inner planet peaks at magnitude –4.9 December 1 and fades only slightly (to magnitude –4.6) by month’s end. It dominates the southeastern sky from the time it rises before 4 a.m. until shortly before sunrise more than three hours later.

Be sure to catch this beacon when a slender crescent Moon hangs 5° above it the morning of December 3. First-magnitude Spica — Virgo the Maiden’s brightest star —appears 7° to the right of this pair. Venus crosses from Virgo into Libra on December 13 and remains there until the end of 2018.

Mercury joins Venus in the morning sky. The innermost planet reaches greatest elongation December 15, when it lies 21° west of the Sun and climbs 10° above the southeastern horizon 45 minutes before sunrise. Mercury then shines at magnitude –0.4 some 24° to Venus’ lower left.

Mercury sinks deeper into twilight during December’s second half. As it descends, Jupiter rises to meet it. On December 21, they stand 0.9° apart. At magnitude –1.8, Jupiter appears more obvious than magnitude –0.5 Mercury. Enjoy this pretty conjunction starting about 45 minutes before sunup, when the pair lies 8° above the horizon. Those with eagle eyes, or binoculars, may notice the 1st-magnitude star Antares 5° to Jupiter’s lower right.

Like Venus, Mercury transitions through a variety of phases — it just does so more quickly. On December 5, Mercury spans 9″ and is one-quarter lit. It appears exactly half-lit on the 11th, although its diameter has shrunk to 7″. Its phase waxes to gibbous after this, reaching 63 percent illumination at greatest elongation. And by the time Mercury passes Jupiter on the 21st, it sports a 6″-diameter disk that’s 77 percent lit.

Jupiter shows none of the dramatic changes the two inner planets do. Its disk spans 31″ at the time of its conjunction with Mercury and grows barely 1 percent by month’s end. Although the giant planet’s low altitude washes out atmospheric detail, conditions will improve dramatically in January.

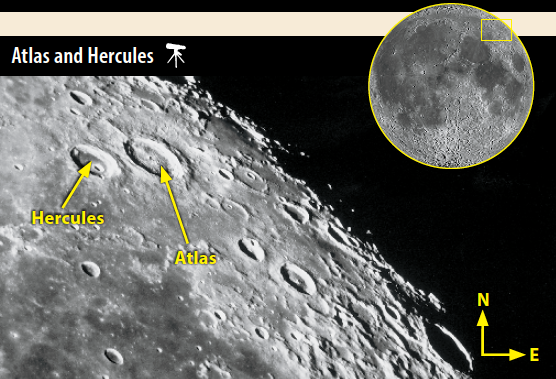

It’s easy to see evidence of volcanic activity on the Moon: Simply look at the large dark “seas” that populate the nearside. These maria are huge expanses of now-solidified lava that erupted from beneath the surface more than 3 billion years ago.

Besides the maria, Luna’s best volcanic features may be a field of domes known as the Marius Hills. This coarse, sandpaper-like terrain lies near the craters Marius and Reiner in the vast Oceanus Procellarum of the Moon’s western hemisphere. The hills see first light the evening of December 19, about three days before Full phase.

You can’t help but notice Tycho’s spectacular ray system and brilliant Aristarchus at this phase. Take some time to enjoy these features, but then boost your telescope’s magnification and shift your concentration to the far west. The Marius Hills lie just north of the equator along the terminator — the line that divides lunar day from night. Although prominent on the 19th, the hills become harder to see on the 20th. And by the 21st, the Sun’s higher elevation has wiped out the shadows necessary to observe this textured terrain.

How did these hills develop? Astronomers think the structures formed through multiple episodes of volcanic activity. A few hundred steep-sided cone volcanoes first erupted on the scene when a huge bubble of magma welled up from below. Less-violent eruptions then built the dome structures. Finally, huge volumes of lava oozed out of cracks and vents, filling much of the surrounding basin. NASA selected the Marius Hills as a target during the Apollo program, but that mission was canceled.

The Geminid meteor shower peaks the night of December 13/14. The waxing crescent Moon sets by 11 p.m. local time on the 13th, and you should have excellent views from then until twilight starts to paint the sky. The meteors appear to radiate from a point in northern Gemini. This region stands more than halfway to the zenith at 11 p.m. and passes nearly overhead between 1 and 2 a.m.

The Geminid shower ranks as one of the three richest showers of the year. But it benefits from the fact that its radiant climbs overhead from mid-northern latitudes, so observers under dark skies have a chance to see the maximum possible rate of 120 meteors per hour.

Don’t stare at the radiant, however. Any meteors you see there will have short trails because you’re seeing them coming almost head-on. Instead, look for the longer trails you’ll see roughly 30° to 60° away from Gemini.

Comet observers haven’t had it this good for a couple of years. Comet 46P/Wirtanen is a relatively active comet that makes its closest approach to the Sun this month just outside Earth’s orbit. And to top things off, we hit the timing almost perfectly: On December 16, Wirtanen swoops within 7.2 million miles of Earth, just 30 times the Moon’s average distance.

The comet’s peak brightness remains the key unknown. Conservatively, it will glow around 7th magnitude and be a decent binocular object. But some astronomers estimate it might reach 4th magnitude, which would make it visible to the naked eye under a dark sky. Either way, you should be able to follow changes to the dusty inner coma through a 4-inch telescope from the suburbs.

The comet also rides high in December’s sky. It resides among the background stars of Taurus at closest approach, between the magnificent Pleiades star cluster (M45) and the 1st-magnitude star Aldebaran. Although this area remains visible nearly all night, it climbs highest in late evening.

Leading up to 16th, we are looking slightly down on the comet’s stubby, fan-shaped dust tail. If it also sports a tail of ionized gas, it should appear as a short spike of green or blue angled to the northeast as the solar wind carries the ions directly away from the Sun.

Significant changes occur in short order. Earth passes through Wirtanen’s orbit on the night of December 15/16. That means we see the tails edge-on and confined to a short, straight line. The best views come after 12:30 a.m. local time when the Moon sets.

Comet observers may also want to track 9th-magnitude Comet 38P/Stephan-Oterma. Our best views of this periodic visitor come in the morning sky during December’s first half, when it lies roughly 10° from Gemini’s twin stars, Castor and Pollux. It makes its closest approach to Earth on the 17th.

Minor planet 3 Juno continues its brief reign as the brightest asteroid. Glowing at magnitude 7.6 in early December, the 170-mile-wide, potato-shaped space rock dims to magnitude 8.2 at month’s end. That makes it bright enough to see with binoculars from the suburbs and an easy target through even the smallest telescope.

Juno reached opposition and peak visibility in mid-November. As Earth sprints ahead of it on the solar system’s orbital race track, Juno climbs higher in the southeastern sky after darkness falls. The majority of main belt asteroids orbit the Sun in roughly the same plane as the planets, known as the ecliptic, but Juno tilts 13° to this plane. That places it well south of the ecliptic this month, plying the relatively star-poor waters of the great celestial river Eridanus, located to the west of Orion.

Use the star chart below to get to the right vicinity. (Or, if you use an equatorial mount, simply slew 28° south of the Pleiades star cluster.) Once you arrive, Juno will be one of the brightest points of light in the field of view. Unlike the crowded, uniform star fields you find closer to the Milky Way, here the uneven background with its wide range of star brightnesses proves useful. You should be able to track Juno’s night-to-night motion with a modest magnification of 50x.