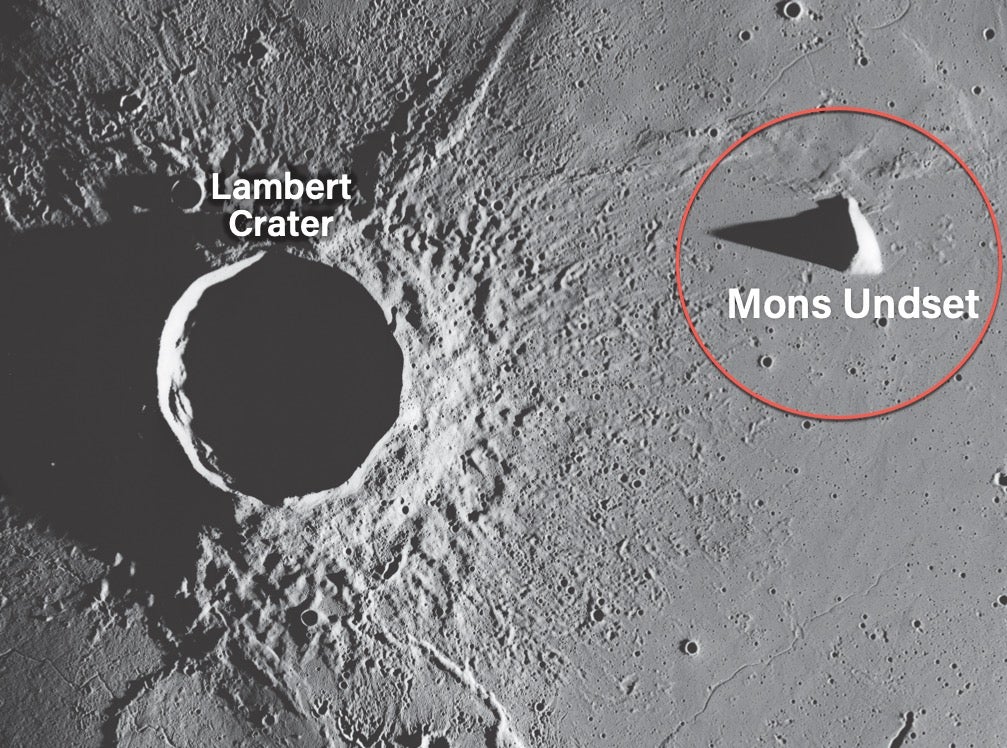

On the evening of Sept. 23, 2023, I was training my 3-inch Tele Vue refractor on the Moon to catch sunrise over Lambert Crater when a brilliant pyramid of light just to the east of the crater grabbed my attention instead. This isolated peak was the brightest feature to emerge from the lunar twilight that night. At high power, the mountain’s sharply cut facets reflected the rising Sun’s rays in the most alluring manner. I immediately had to know the mountain’s name, only to discover … it has none.

But it did once! I’ll explain.

The next morning, I checked NASA’s online Scientific Visualization Studio’s Moon Phase and Libration (which displays the Moon on any chosen date with countless labels), as well as the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera ACT-REACT QuickMap, but neither site identified this peak. Nor was the mountain listed in the International Astronomical Union’s (IAU) Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature for the Moon.

Doubtful that such a bright feature went unnamed, I went back in time to the 1913 Collated List of Lunar Formations. Sanctioned by the International Association of Academies, this work was the first attempt to remedy the unsatisfactory state of lunar nomenclature of the day. (At that time, the Moon’s most prominent features were known by at least three different names, depending on the source.) I was not disappointed: The Collated List provides us with the first official mention of our target mountain’s name: Lambert Gamma (Γ).

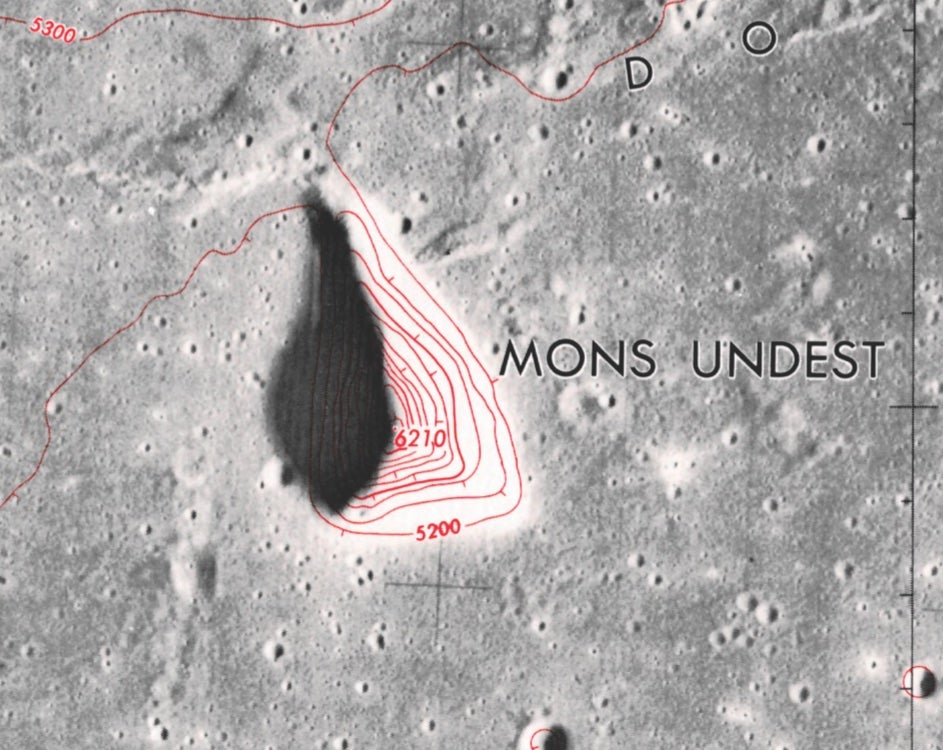

German astronomer Johann Henrich Mädler assigned that name to the mountain in his and Wilhelm Beer’s Mappa Selenographica (1836), which was then the universally accepted standard in selenography. Mädler’s convention was to name isolated lunar peaks wtih the name of a nearby crater followed by a Greek letter. In his 1876 book The Moon and the Condition and Configurations of Its Surface, Edmund Neison gives a wonderful description of Lambert Γ: “Owing to its curved form, the mountain Γ … appears at times like a crater … Occasionally this peak glitters on the terminator in a very striking manner.”

Lambert Γ’s uppercase Gamma was changed to the lowercase Lambert γ in the 1935 Named Lunar Formations, the first official list of IAU nomenclature. When the IAU discontinued the use of Greek letters for elevated features in 1973, Lambert γ was renamed Mons Undset, in honor of Sigrid Undset, a Danish-born Norwegian novelist who won the 1928 Nobel Prize in literature.

Unfortunately, when Undset’s name was applied to her lunar mountain in the 1973 Lunar Topographic Orthophotomap Series — the first comprehensive and continuous mapping based on photographs from Apollo 15, 16, and 17 — her name was misspelled “Undest.” Rather than fixing the mistake, the IAU stripped the mountain of its name, leaving it in nomenclature limbo.

Most references today lean toward unofficially renaming the mountain Lambert γ, (see the Astronomy Magazine Guide to the Moon .PDF here) but why take away an honor bestowed upon a great woman just because of a typo? (For what it’s worth, in 1985 the IAU named a crater on Venus in Undset’s honor — but we cannot visually admire this sight.)

My observation of Mons Undset occurred at lunar colongitude 18.3˚, which must have been one of the occasions Neison mentioned, when the mountain appears as a striking site near the terminator. But Mons Undset is so unusual at times that observers have mistaken it for a lunar transient phenomenon. So, it’s a sight worth pursuing — and remembering.

In her book Christmas and Twelfth Night, Undset writes, “Let us remember that He has given us the sun and the moon and the stars.” And lest we forget, we gave her a mountain on the Moon. As always, send your thoughts to sjomeara31@gmail.com.