As darkness deepens, visitors appear. A young woman shows up with a male companion in tow. “I’m so excited,” she says.

“I saw this announcement in the neighborhood bulletin, and I texted everybody.” Saturn finally peeks through the gloom, and Nichols turns her scope on the ringed giant, bringing it into focus.

“Okay,” she tells the young woman, stepping back. “Go ahead.”

She leans over and her face lights up. From behind the eyepiece, she exclaims, “This is the best day of my life!”

Megan Gorzkowski, like most of the other visitors, has never looked through a telescope before, though she says she has long been a space fan. But the star party came right to her neighborhood tonight. So for roughly an hour and a half, she hangs out and mingles with the astronomers. And she isn’t alone. Most of the more than two dozen attendees, whose ages range from a few months to past middle age, stick around for the duration of the event.

The limited seeing doesn’t seem to bother them. They ask about the motor on the go-to scope, the Dob’s Lazy Susan base, and the backgrounds of the astronomers gathered around. They duck in for second, third, and fourth looks at Saturn and its rings. Nichols encourages them to steer the Dob on their own to follow Saturn’s surprisingly swift path, and they pan around the Moon’s surface, learning words like “ray” and “terminator.”

If you ever find yourself lamenting the dearth of new blood in astronomy: This is how you fix it.

Even in America’s biggest, most light-polluted cities, astronomy lovers reach out to each other to share their passion, as well as some surprisingly nice telescopes.

Hollywood stars

Los Angeles, CA

Whatever your thoughts on city observing, one place should spring to mind immediately: Griffith Observatory reigns as the most popular in the world, with more than a million visitors per year. Perched just above the smog and lights of Los Angeles, a stone’s throw from the famed Hollywood Sign, Griffith has since its inception not just tolerated its urban status, but embraced it. But even with a state-of-the-art planetarium and plenty of museum-style exhibit space, the staff still prioritize true telescopic observing above all else. “We’re in business to put people eyeball to the universe,” says E. C. Krupp, director of the observatory. “That’s what Colonel Griffith originally intended, when he conceived of a public observatory and left money in his will for it.”

Since 1935 (except for a five-year break in the early 2000s for renovations and expansions), Griffith has entranced visitors, especially locals, with its stately white walls and active approach to astronomy that casts each visitor as an observer. “The architecture, the exhibits, the planetarium … all of this is really designed to make people fall in love with the sky, astronomy, and the place,” Krupp explains. “And in fact Griffith really is one of the most affectionately regarded places in Los Angeles. Everybody knows they own it; it’s municipal.”

With anywhere between hundreds of people on a slow night and thousands on special occasions, the numbers support Krupp’s assessment of its popularity. Located high on its hill, the observatory requires a little dedication to visit, but sky lovers flock there nonetheless. Griffith boasts a 12-inch Zeiss refractor, and Krupp is proud to tell me that more people have looked through it than any other telescope in the world. Every night when the skies are clear, portable telescopes dot the lawn and once a month, the Los Angeles Astronomical Society, Los Angeles Sidewalk Astronomers, and Planetary Society members join in as well to host star parties. Even and especially when sky events occur that would be visible anywhere — eclipses, comets, or the 2012 Venus transit — visitors appear at Griffith in droves. “The observatory is sensed as a place you can make contact,” Krupp says. “Something special happens here.”

New York City, NY

If Griffith is about making a pilgrimage to astronomy, New York takes the opposite tack. The Amateur Astronomers Association (AAA) brings their telescopes to the people, engaging in guerilla-style stargazing to find pedestrians in neighborhoods all across the city. Their favorite spots include High Line Park and Lincoln Center, both well traveled, brightly lit areas that are no one’s idea of a great observing site — at least by traditional thinking.

Ten years ago, the club would meet in the darkest spots they could find in the city — hilltops far uptown, even cemeteries, relying on would-be observers following “breadcrumbs,” such as balloons tied to park benches, in order to find the telescopes. “But it was still urban observing,” complains Marcelo Cabrera, the club’s president. “It was a darker area, but that also made it perhaps more unsafe and inaccessible.” Their novel approach began in 2009, with the International Year of Astronomy. “We just told our members to go out, let us know where you’re going to be, but don’t go farther than two, three blocks from where you live,” he says. “And most people said, ‘Well there are a lot of people there, and streetlights.’ Perfect! That’s what we want! We’re going to do the experiment.”

By any reasonable metric, the experiment worked. Cabrera reports a few thousand visitors every Friday and Saturday night when the weather is good. Many are tourists, adding a star party to an activity list that also might include walking through Times Square or taking in a Broadway show. But the locals also show up in force, some of them even becoming regulars, though Cabrera admits they have far more attendees than dues-paying club members.

The AAA’s reach is enormous. In addition to weekly observing sessions scattered across the city, it still holds bigger annual star parties and special events, as well as trekking outside the city to hold dark sky events for its more dedicated members. The crowds keep the AAA busy, but Cabrera says members and visitors both enjoy the new normal. Members find themselves viewing the same urban-limited targets they used to, but with far greater impact and without the strain of carting telescopes up muddy hills or venturing into dark corners of the city. And newcomers find the club more easily — stumble across it, in fact, allowing the AAA to recruit people who never knew an astronomy club was an option in the heart of Manhattan.

Fort Worth, TX

But how do you turn these one-time visitors into regular astronomers? Visitors to the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History provided their own solution according to Sarah Twidal, who manages their monthly star parties with the help of the Fort Worth Astronomical Society.

“A lot of people bring out their telescopes and they’ve never used them before,” she says. “They’ve been sitting in a closet picking up dust. The astronomers will just jump up and help put them together, figure out how to use them. That’s increased our return visits greatly. A lot of people who come are regulars, who started to love this place because they’ve been lent a helping hand by the local astronomy society.”

Outreach is actually a foundational component of the club. In 1947, a retired math teacher named Charlie Mary Noble founded the Junior Astronomy Club at what was then called the Fort Worth Children’s Museum. A self-taught astronomer, Noble led weekly meetings where students observed and recorded the skies. She put together a lending library of telescopes and formed a team for Project Moonwatch (a nationwide effort to track Sputnik and other Soviet satellites). The current astronomical society grew out of her club and maintains its close ties with the museum, as well as her supportive and inclusive example.

“People are intimidated by astronomy,” observes Bruce Cowles, president of the astronomical society. He combats this feeling by encouraging all visitors to ask questions. “We love talking about this stuff, so we don’t mind talking about it to you, ever … To see people so excited keeps us excited.”

And if the subject matter intimidates some, the mechanically disinclined can be equally wary. “The equipment is also intimidating,” Cowles adds. In addition to helping new observers set up and understand their equipment, his club also stresses that you can enjoy the hobby without straining your purse strings. “We don’t want to be telescope snobs,” he says. His club utilizes tiny Dobsonians that can perch on picnic tables and binoculars on tripods, as well as reflectors from 8 to 12 inches, a large refractor, and often a homemade scope or two. “We try to have a range, so people don’t think they have to spend a fortune,” Cowles explains.

Their consideration seems to be paying off. The club is growing rapidly, with new members almost every month and an active Young Astronomers Club that carries on the heart of Charlie Mary Noble’s mission.

Atlanta, GA

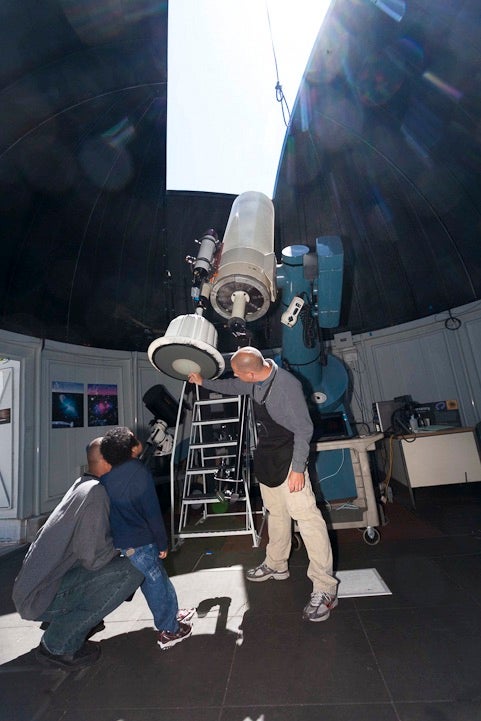

Not all astronomy clubs are as naturally dedicated to servicing the broader community. In Atlanta, Fernbank Science Center had to defend its 36-inch Cassegrain reflector from an understandably covetous astronomy club who wanted to see the telescope relocated to darker skies some 95 miles outside the city. But nearby Agnes Scott College provided a cautionary tale. The school relocated their 30-inch telescope to a remote site to escape light pollution, only to find that its use plummeted, as even astronomy students tired of the long commute. They eventually moved it back to campus, where it now enjoys both public and academic use.

Ed Albin, who has been an astronomer with Fernbank since 1988, was keen to prevent history from repeating itself. “We listened to [the astronomy club’s] request,” he says, and acknowledges the obvious allure of a large-aperture, public telescope under dark skies. But for him, the decision to keep the instrument at the science center was an easy one. “We know that the public really would not go out there on a regular basis,” he says. “We wouldn’t captivate children and families like we do here in the city.”

While the standard urban-attainable targets of the Moon and planets figure prominently in the museum’s observing repertoire, 36 inches, even in Atlanta, also reaches not just the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) and bright globular clusters, but even planetary nebulae like the Ring Nebula (M57) and the Ghost of Jupiter (NGC 3242).

The observatory is open every Thursday and Friday evening and sees between 100 and 200 visitors a night, though thousands may appear for special occasions. For the 2003 opposition of Mars, Albin recalls opening the observatory when the Red Planet rose. “We shut down when we lost it in the trees in the west around 5 a.m. and we still had literally hundreds of people.”

Washington, D.C.

On the other hand, as with the other observatories and science centers, Fernbank’s guests have already made the first step toward becoming an observer simply by choosing to visit. “When you have a public night, when they come to you, these are people who already think astronomy is for them,” explains Shauna Edson, an educator with the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum’s Phoebe Waterman Haas Public Observatory. “When you go outside the observatory, you get a totally different group of people. The beauty of it is that it’s a surprise. The sidewalk astronomy element is exactly that they find you unexpectedly.”

She should know. Their program has a bit of both approaches. The observatory nestles close to the museum’s Washington, D.C., location and houses a 16-inch telescope that once belonged to Harvard College Observatory and is now on indefinite loan to the museum. Wednesdays through Sundays, museum-goers can augment their visit with solar observing. And by sitting right on busy Independence Avenue, only a block off the National Mall and in the heart of the cluster of other Smithsonian buildings, the observatory attracts plenty of foot traffic — at least during daylight hours.

The museum’s semiregular series of evening talks entices some of them back. Visitors can use the 16-inch scope to view Jupiter, Saturn, or perhaps a bright star cluster, and volunteers also bring out smaller telescopes to join in the fun. Some observers are regulars, fans of the museum and stargazing, and thrilled to have such a resource in their own city. Many are tourists from around the world.

But without such special events, pedestrians are in short supply. And the resource cost to keep the museum open so long after hours is a strain. So the observatory is in the process of launching their own guerilla astronomy program, planning to bring their portable telescopes on the metro and strike areas like busy residential Arlington, or the well-traveled and bustling Navy Memorial or Chinatown — locations with metro access and lots of evening foot traffic.

The high ratio of tourists to locals at the museum makes it impossible to track how many star party attendees find their way back to a telescope in the future. But the wonder and excitement they so obviously display makes it clear the organizers have shared something special with them, whether that manifests in a newfound interest in observing, a general affection for space and science, or simply a sense of wonder and beauty in the universe.

Chicago, IL

Back in Chicago, Nichols hands out free passes to the Adler Planetarium to anyone who stops by the star party, hoping to encourage more than a one-time interest in the cosmos. The landmark planetarium is halfway through renovations on their 20-inch Doane telescope, which looks out over the lake. The observatory now boasts viewing screens and easier access, and upgraded electronics are forthcoming. Volunteers are coming up to speed as fast as Adler can train them on the Doane, which is equipped during the day for solar viewing and open whenever they have cooperative weather and the staff to operate it.

“ ’Scopes in the City,” the name given to these frequently occurring star parties, continues to pick up steam. “Last year we only had four events in our pilot program,” Nichols says. “This year we have 25 on the books, extending our reach into communities that may not have access to experiences such as this.”

As a fledgling program, it’s hard to say yet what effect ’Scopes in the City is having on Chicagoland neighborhoods and their residents. But at one point, two visitors almost simultaneously approached Nichols from opposite sides, wanting to know when and where the next event will be held. For them, at least, the astronomy bug had bitten.

Adler’s ’Scopes in the City exemplifies the best way to attract newcomers to any hobby: Be friendly. Be convenient. The former simply requires remembering what it was once like to be inexperienced at a new hobby and uncertain of your welcome in a strange community. As to the latter, what’s more convenient than finding people where most of them live?

Whether you’re an Astronomy reader who has yet to try observing first hand, or a veteran observer who wants to make some new friends, consider heading downtown. Despite the bright lights, the nearest star party may be closer than you think.