Scholars across the globe often refer to astronomy as the oldest science, dating back to the ancient Mesopotamians and Babylonians. While that may be true, modern-day amateur astronomy can trace its origins back to Dec. 7, 1923. On that date, the first meeting of a small club known as the Springfield Telescope Makers sparked a movement that continues to this day.

Born in Springfield, Vermont, in 1871, Russell W. Porter exemplified a 20th-century Renaissance man. He was an artist, an architect, an engineer, and an arctic explorer. It was on those excursions around the Arctic Circle that celestial navigation, astronomy, and telescopes began to pique his interest, paving the way for a lifelong hobby.

After his arctic adventures ebbed, Porter moved to Port Clyde, Maine, and got married. He made a living designing new oceanfront cottages and renovating older buildings. But by night, the dark Maine skies beckoned him to learn more about the universe.

In 1910, Porter’s longtime friend and enthusiastic amateur astronomer James Hartness began introducing him to articles in Scientific American and Popular Astronomy magazines, to fuel his interest in astronomy. One issue included an intriguing article written by Leo Holcomb on speculum (or mirror) making. Although the article was only a general introduction to the subject and did not contain actual instructions on mirror grinding, it was enough to prompt Porter to write to Holcomb, asking for more information.

Holcomb began corresponding with Porter, sending a copy of the book Glass Working by Heat and by Abrasion by Paul Hasluck with one of his letters. This book was just the thing Porter needed to begin crafting his first telescope lens. In a later article in Popular Astronomy, he wrote, “Since that time, I have figured a dozen or more discs for telescopes, and derived so much pleasure from the pastime that I wish to pass on to others, who may enter on this fascinating work, the benefits of my experience.”

Meanwhile, to cope with the intensely cold winter nights in northern New England, Hartness had devised a clever “indoor observatory” that kept the optics of his 10-inch refractor outside in the cold to prevent distortion, while the observer stayed in a heated room.

Inspired by Hartness’ design, Porter created a similar observatory for his home, featuring a reflecting telescope. The excellent quality of his new observatory prompted Porter to write an article about its design for the May 1916 issue of Popular Astronomy. It was the first of many articles to come.

Expanding the scope

In 1915, Porter joined MIT as a professor; he then worked at the National Bureau of Standards during World War I. But in 1919, Porter moved back to Springfield with his wife Alice and young daughter Caroline. He got a job with Hartness at Jones & Lamson Machine Co., a large manufacturer of small mechanical parts.

Porter’s fascination with telescope-making soon proved contagious and by 1920, many fellow townsfolk had become interested in the hobby, prompting Porter to start teaching classes. Eventually the members began hauling their completed telescopes all over town for observing sessions. One favorite spot was land owned by Porter atop Breezy Hill, just outside Springfield.

On Dec. 7, 1923, the Springfield Telescope Makers club was born, with Porter elected as president. Around the same time, members began constructing a clubhouse on the summit of Breezy Hill. The building consisted of a main meeting room and two upstairs bedrooms, and later a kitchen.

In 1924, the club adopted Porter’s proposal that the site be christened Stellar Fane, Latin for “shrine to the stars.” Within months, the name was shortened to Stellafane.

Porter spread the word about Stellafane within the pages of Popular Astronomy. In 1925, after reading Porter’s articles in the magazine, editor Albert Ingalls met with him to learn about the telescope-making process and the Springfield club. Ingalls subsequently visited Stellafane to meet with members.

Ingalls’ article about Porter’s club and their homemade telescopes made the cover story of the November 1925 issue of Scientific American. The response was almost immediate. Readers wanted to know how to build their own instruments. At the time, most commercial telescopes were high-priced refractors, impossible for many amateurs to purchase. Porter’s articles ignited an excitement that the average person could make their own telescope, even on a limited budget.

The popularity of that article helped Ingalls convince Porter to write two articles on amateur telescope-making for Scientific American. They appeared in February and March 1926. Letters from interested readers around the world poured in, and Porter soon became a corresponding editor for the magazine.

The reaction also prompted the club to invite amateur telescope makers to Stellafane for a weekend gathering to exchange ideas and compare their creations. On July 3, 1926, about 20 people ventured up the dirt roads to the summit of Breezy Hill to attend the first Stellafane convention.

Growing interest in amateur telescope-making prompted Ingalls to compile a book with step-by-step instructions, called Amateur Telescope Making. He included Porter’s first two articles from Scientific American, along with several new chapters. Published in 1926, it has since become the amateur telescope maker’s bible.

This continued to fuel a movement that changed the face of the hobby forever. Rather than spending a fortune on a small refractor, the growing field of amateur astronomers preferred to make their own larger Newtonian reflectors for less money. Meanwhile, the Stellafane convention became an annual event.

In 1928, Porter met with astronomer George Ellery Hale, who had read some of his articles. Hale was in the early planning stages of installing a 200-inch (5.1 meters) reflector — the world’s largest telescope at that time — on Palomar Mountain, 61 miles east of San Diego, California. Later that year, Porter received a telegram from Hale, asking him to come to California “to assist in designing the 200-inch telescope.” Porter did not hesitate to accept.

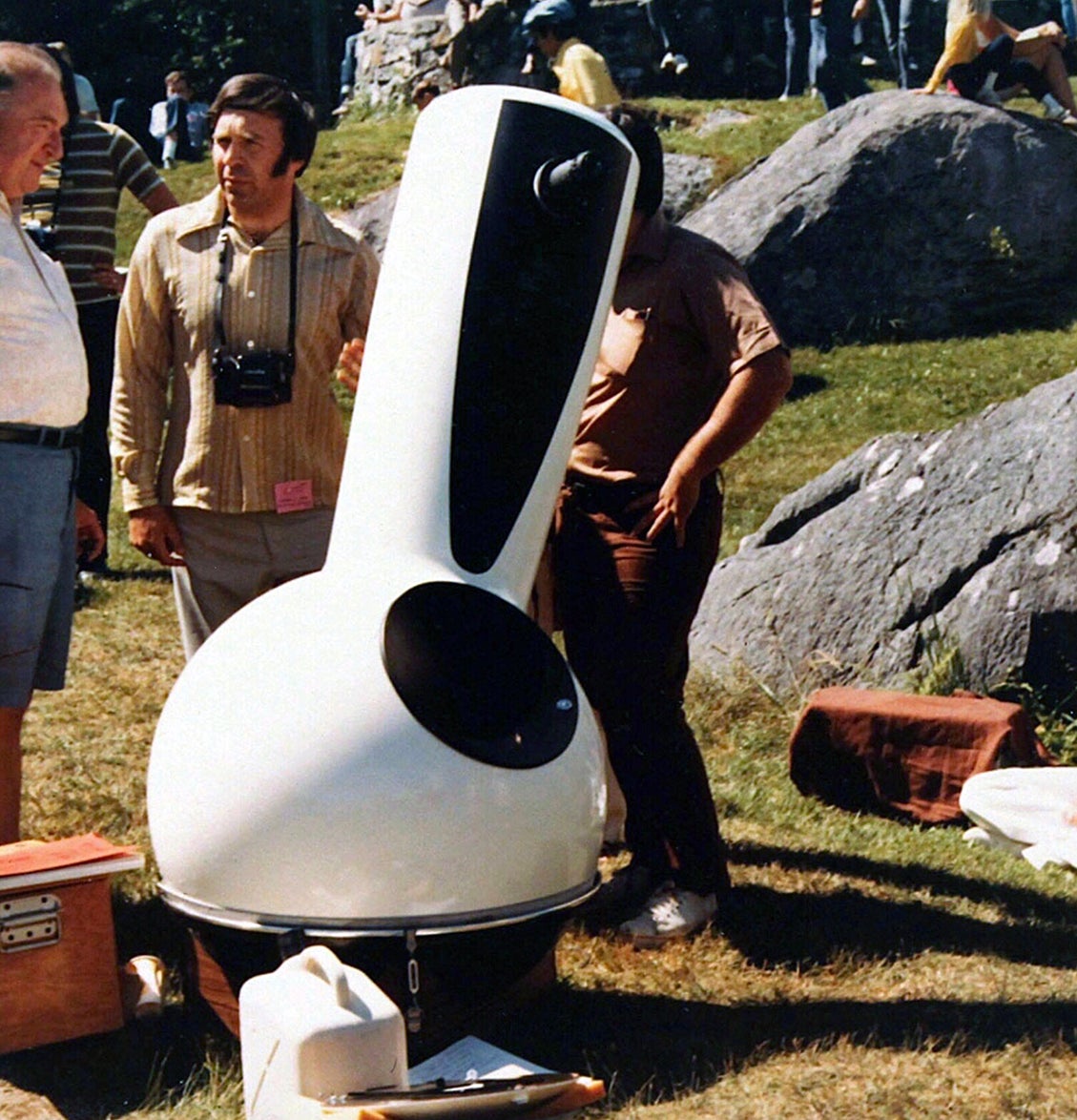

Porter expected his involvement would be brief, but it soon became clear that the move to California was permanent. He relinquished his club presidency but still managed to attend many Stellafane conventions. During a club meeting in 1929, Porter revealed plans to build a telescope on a massive rock on Breezy Hill, just north of the clubhouse. The ingenious design called for a new observatory building surrounding the scope to double as a shelter and telescope mount. A circular opening in the north wall, sloped to match the property’s grade, would be capped with a rotating turretlike dome that would serve as the telescope’s right ascension axis and viewing portal. Incoming light would reflect off a rotatable diagonal mirror to the instrument’s primary mirror, which would direct it back through a hole in the diagonal and into the eyepiece inside the observatory. The partially constructed turret telescope was one of the chief attractions at the fifth annual convention and by the sixth in 1931, the Porter Turret Telescope was complete.

World War II forced the suspension of the Stellafane conventions from 1942 to 1945. The first postwar Stellafane in 1946 drew over 350 people, the largest crowd at the time.

Porter’s failing health kept him from the 1948 convention, but he sent a letter that was read at the event’s Twilight Talks. “You may be sure that I regret not being with you tonight, but the stress of other work has made it impossible,” Porter wrote. “But I am very much with you in spirit.”

On Feb. 22, 1949, while working Porter suffered a major heart attack. Around 11:30 that night, he experienced a second, fatal heart attack. He was 77 years old.

Among the many honors and awards bestowed on Porter, the most unique was the posthumous renaming of a lunar crater in his honor. Today, Porter Crater is located in the southern portion of the Moon, inside Clavius Crater.

The modern era

Porter’s death left a huge void, but the Stellafane conventions eventually recovered. His spirit lives on to this day in every telescope and other equipment displayed each year. Most of the instruments at Stellafane are Newtonians, though other types of telescopes are also present. Occasionally, a telescope displayed on Breezy Hill features a breakthrough in design.

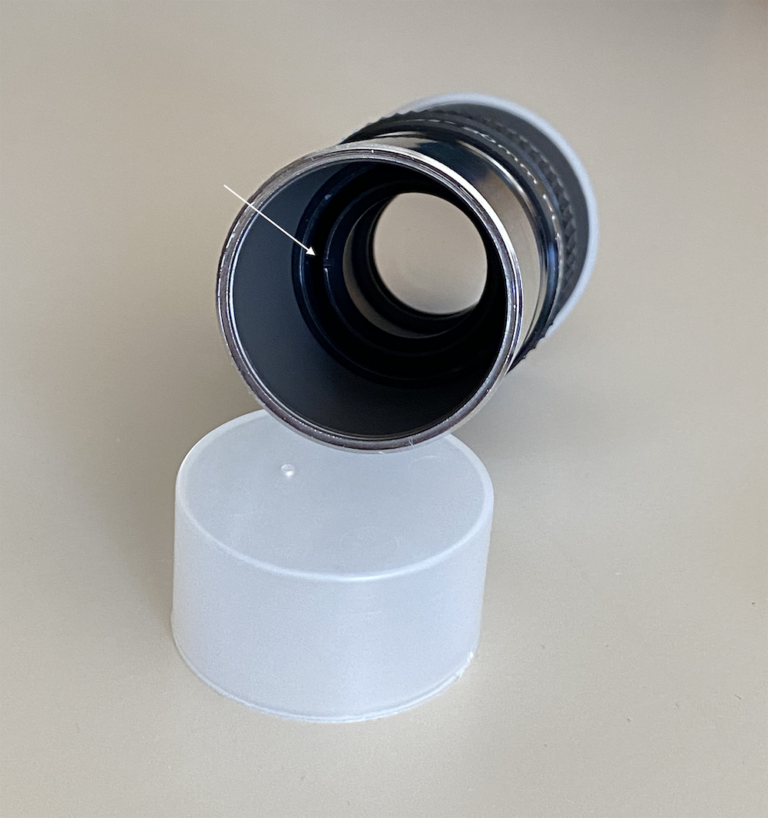

One such instrument was John Gregory’s 5-inch Maksutov at the 1956 convention. Gregory, an optical designer from Stamford, Connecticut, modified the shape of the corrector plate so that an aluminized spot at its center served as the secondary mirror, rather than requiring a separate mirror. Today, most commercial Maksutovs use his innovative design.

My first year at Stellafane, 1969, featured a solar observatory assembled on Breezy Hill by Walter Scott Houston. Inside the small plywood building, an 18-inch-diameter (45.7 centimeters) image of the Sun appeared on a rear projection screen.

During all those gatherings, I have seen some incredible instruments. Some have been works of art, like the 12.5-inch ball-mount reflector by Norman James in 1972, the monstrous 22-inch reflector by Steve Dodson in 1981, the even larger 32-inch reflector by John Vogt in 1998, and a stunning pair of 6-inch Alvan Clark reproduction refractors by Allen Hall and Dick Parker in 2016. Then, there are the great telescopes made by first timers and juniors, like the award-winning 4.5-inch reflector last year, made by teenage sisters A.K. and Sydney Burke.

Today’s conventions offer something for everyone, including mirror grinding demonstrations, “Observing Olympics,” and a range of talks for all levels of attendees. But what is it about this place that makes so many people return there every year? Is it the excitement of seeing some of the most exquisitely fashioned amateur-made telescopes ever created? Perhaps it’s the sense of walking in the shadows of giants, like Porter and Ingalls. Maybe it’s the swap tables, where bargains in telescopes, optics, and more can be found. It could be the prospect of observing under some of the clearest skies all year. Or is it the camaraderie that one feels as the ever-growing Stellafane family returns for a huge annual reunion?

It’s all this and more. Stellafane is not just a place, it’s a spirit — the same spirit that drove a dozen people up to the same spot a century ago to erect a monument to the heavens. Russell Porter said it best in the letter he sent to the 1948 Stellafane convention, “There will never be another Stellafane.”

Why is Stellafane painted pink?

Today, One of the most common questions people ask is “Why is the Stellafane clubhouse painted pink?” The answer is steeped in legend. One story says that a local merchant donated paint but did not specify the color; the telescope makers later discovered that the paint was pink. Another version claims that Porter wanted to paint the clubhouse spruce-gum pink, which is white with the faintest hint of pink. But club members misunderstood and painted the clubhouse that vibrant “Stellafane pink.” Whichever story is true — if either — is lost to history, but the clubhouse remains the candy-colored shade to this day.