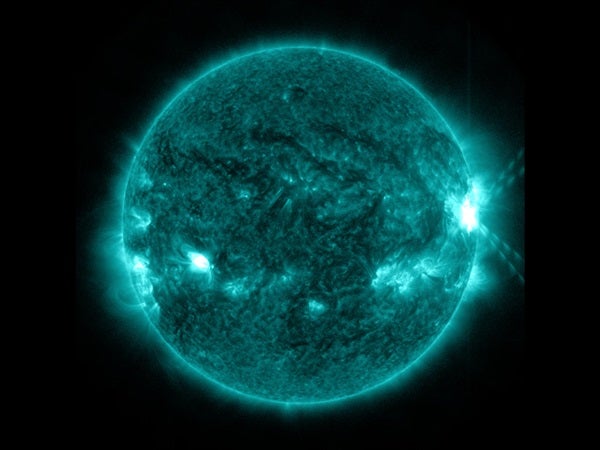

Solar flares are powerful bursts of radiation. Harmful radiation from a flare cannot pass through Earth’s atmosphere to physically affect humans on the ground; however, when intense enough, they can disturb the atmosphere in the layer where GPS and communications signals travel.

One of the larger flares was classified as an X1.0 flare, which peaked at 10:03 p.m. EDT on October 27. “X-class” denotes the most intense flares, while the number provides more information about its strength. An X2 is twice as intense as an X1, an X3 is three times as intense, etc. In the past, X-class flares of this intensity have caused degradation or blackouts of radio communications for about an hour.

Another large flare was classified as an M5.1 flare, which peaked at 12: 41 a.m. EDT on October 28. Between October 23 and the morning of October 28, there were three X-class flares and more than 15 additional M-class flares.

Increased numbers of flares are quite common at the moment since the Sun is headed toward solar maximum conditions as part of its normal 11-year activity cycle. Humans have tracked this solar cycle continuously since it was discovered in 1843, and it is normal for there to be many flares a day during the Sun’s peak activity.

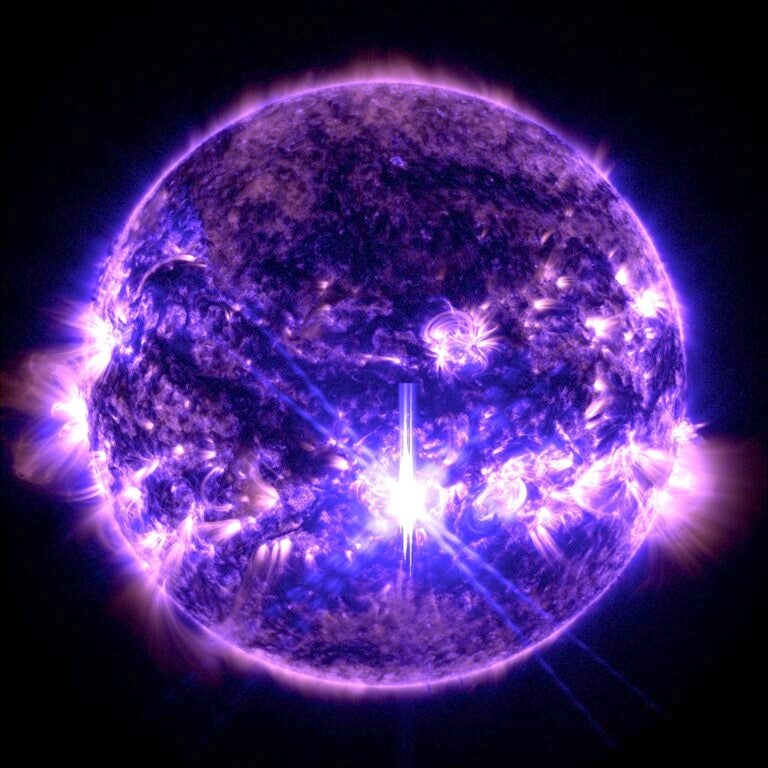

The recent solar flare activity also has been accompanied by several coronal mass ejections (CMEs), another solar phenomenon that can send billions of tons of particles into space that can reach Earth one to three days later. These particles cannot travel through the atmosphere to harm humans on Earth, but they can affect electronic systems in satellites and on the ground.

Experimental NASA research models, based on observations from NASA’s Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory and ESA/NASA’s Solar and Heliospheric Observatory show that five CMEs, traveling at different speeds, may join up into a single moving cloud of particles.

CMEs can cause a space weather phenomenon called a geomagnetic storm, which occurs when they funnel energy into Earth’s magnetic envelope, the magnetosphere, for an extended period of time. The CMEs’ magnetic fields peel back the outermost layers of Earth’s fields, changing their very shape. Magnetic storms can degrade communication signals and cause unexpected electrical surges in power grids. They also can cause aurorae. Storms are rare during solar minimum, but as the Sun nears solar maximum, large storms occur several times per year.

In the past, geomagnetic storms caused by CMEs of this size, speed, and direction have usually been mild.