Skywatchers from Canada to China are making preparations for next week’s rare planetary shadow play. On Wednesday, November 8, the planet Mercury will be visible in silhouette as it slides across the Sun’s face. The event, called a transit, lasts about 5 hours as Mercury, which orbits the Sun in just 88 days, laps Earth.

But amateur astronomers won’t be the only ones watching. Sun-observing satellites like NASA’s Transition Region And Coronal Explorer (TRACE), Japan’s newly orbited Hinode, and the joint NASA/ESA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) also will see the event.

| Watch Mercury transit the Sun from your desk |

| The Exploratorium in San Francisco |

| NASA’s Sun-Earth Day web site |

| Hawaii’s AstroDay |

Jay Pasachoff at Williams College in Massachusetts hopes to use observations of Mercury from TRACE and Hinode to confirm his ideas about the so-called black-drop effect. This optical illusion, in which a dark thread appears attached to a transiting planet long after its disk has moved onto the Sun, stymied 18th- and 19th-century astronomers who tried to use Venus transits to measure the Sun-Earth distance. Its visibility depends in part on how sharply a telescope brings light to a point, but Pasachoff has identified other effects as well.

Observers under clear skies across North America will be able to see portions of the event before sunset, but the entire transit will be visible in its entirety for those near the West Coast. Mercury will look like a small, dark sunspot as it moves across the solar surface. A properly filtered telescope will provide the best view, because Mercury will appear only 1/194 the Sun’s size. A brief glimpse of the Sun through a telescope can permanently damage vision, so observers must use safe Sun-viewing techniques, such as using proper filters or projecting the image onto paper.

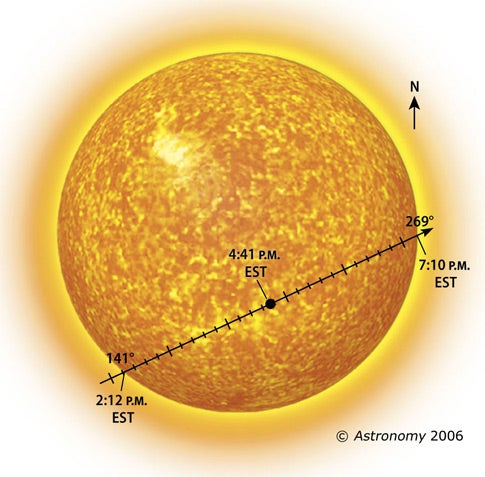

Mercury begins its star trek at 2:12 p.m. EST, when its disk first appears to touch the Sun’s limb as seen from Earth. Two minutes later, and for the next 4 hours and 54 minutes, Mercury’s entire disk appears against the bright solar surface. At 4:41 p.m. EST, Mercury makes its deepest solar incursion, passing just 7’03” away from center of the Sun’s disk. The transit ends at 7:10 p.m. EST as the planet slips off the Sun’s edge.

Mercury last transited the Sun in May 2003, and next week’s event marks the planet’s second of 14 transits this century. From Earth, only the planets Mercury and Venus can transit the Sun, and both events are relatively rare. After November 8, Venus will be the next planet to cross the Sun, in June 2012. Mercury follows suit 4 years later, in 2016.

Why are Mercury transits so rare? Mercury’s orbit is tipped with respect to Earth’s and crosses the plane of our orbit at only two points. For a transit to occur, Mercury must lie near one of those points when it passes us. To meet these conditions, Mercury must slip between Earth and the Sun within 3 days of May 8 or within 5 days of November 10.

The unequal size of these “transit zones” reflects the eccentricity of Mercury’s orbit, which gives us twice as many transits in November as in May. Mercury lies farther from the Sun and moves much slower in May, which reduces our chance of catching it in the right place. But Mercury’s disk appears 20-percent larger during May transits because it’s closer to us then.