Key Takeaways:

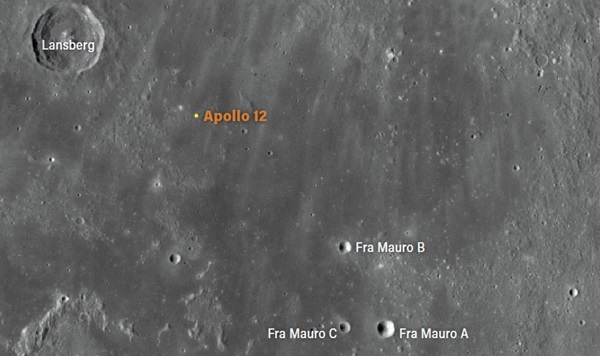

The 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 is the perfect time to view the places where the Apollo astronauts landed. If you’re a Moon watcher — and even if you’re not — you need to check these six sites off your lifetime observing list. While no telescope, not even Hubble, can pick out the actual Apollo hardware that remains on the lunar surface, it’s not hard to find the half-dozen spots where 12 moonwalkers made history.

When and where to look

Ironically, the worst time to view the Moon is when it’s Full and at its brightest. That’s when the Sun’s light hits our satellite straight on, which minimizes the shadows and reveals scant detail.

There are two prime times for lunar viewing. The first one lasts from when the thin crescent becomes visible after New Moon until about two days after First Quarter (in the evening sky). The second one lasts from about two days before Last Quarter to almost New Moon (in the morning sky). Shadows are longer then, and features stand out in sharp relief. This is especially true along the Moon’s shadow line — called the terminator — that divides the light and dark portions. Before Full Moon, the terminator shows where sunrise is occurring; after Full Moon, it marks the sunset line. So, when you’re looking at the Moon, the terminator is where most of the action is.

Two-part landscape

Scientists differentiate features on the Moon between lighter areas, called highlands, and darker features, called maria (the Latin word for seas). The dark material inside maria is solidified lava, and it dates back to periods of volcanism that ended about a billion years after the Moon formed (which happened some 4.5 billion years ago).

But the lava isn’t even the oldest part of the Moon. That honor goes to the highlands, which consist of ancient lunar surface rock and materials thrown out during previous explosive impacts. The highlands are a Moon watcher’s treasure-trove of mountains, valleys, bright areas, and shadows.

Then there are the craters. Of the 9,144 named features on the Moon, 8,737 (nearly 96 percent) are either craters (1,624) or satellite features (7,113). (Satellite features are small craters outside the main ones that carry the main crater name plus a letter — for example, Archimedes M.)

Many more craters dot the highlands because these areas have been around longer than the maria, which were resurfaced by their volcanic activity. Craters range in size, so a fun way to challenge yourself is by noting the size of the smallest crater you can see.

A few tips

The Moon is a bright object, and it’s even brighter through a telescope. Many observers use a neutral density filter to cut down the light. Manufacturers sell small ones that screw into the barrels of eyepieces.

If you don’t have access to such a filter, try these two methods of reducing the Moon’s brilliance: high magnification and a device called an aperture mask. The first restricts the field of view by magnifying it so that you’re looking only at a small area of the lunar surface, thereby reducing the amount of reflected sunlight. The second is a simple cardboard mask with a small hole cut out of it. If you cover the front of your telescope with it, less light will get through, and it will be like using a smaller scope. If you’re using a refractor, you can center the hole. For reflectors and catadioptric scopes, you’ll need to offset the hole from the center, so it doesn’t fall atop the secondary mirror. If you have a reflector, which uses four metal vanes to support the secondary, place your cardboard mask so the hole is between two of the vanes.

For those who want the best possible view of the Moon, turn on a white light behind or beside you as you sit at the telescope. As long as you can’t see the light directly, the placement doesn’t matter. Adding ambient light suppresses your eye’s tendency to adapt to the dark and causes it to use normal (daytime) vision, which is of much higher quality than night vision. This definitely is not what you want if you’re looking at a deep-sky object, but it works on the Moon because it’s so bright.

Scope out the Moon

Now you’re ready to head outside, set up a telescope, and search for the Apollo landing sites. The best way to start is to familiarize yourself with each of the six images of those regions you’ll find in this story.

Do note, though, that your scope might produce images that are upside down, flipped, or both. So, you might need to rotate the appropriate page. For scopes that flip images left to right, it might be best to photocopy each image, then shine a light on the front of the page while you look through the backlit side.

With these maps as starters, tracking down the spots where humans walked on the Moon might be easier than you think. Take your time, have fun, and good luck with “one small step” into lunar observing