Buying a telescope is a big step, especially if you’re not sure what all those terms — f/ratio, magnification, go-to — mean. So, to eliminate confusion and make sure you understand what you’re buying, here’s what to check out before you write the check out.

1. I know telescopes make things appear bigger, but what exactly do they do?

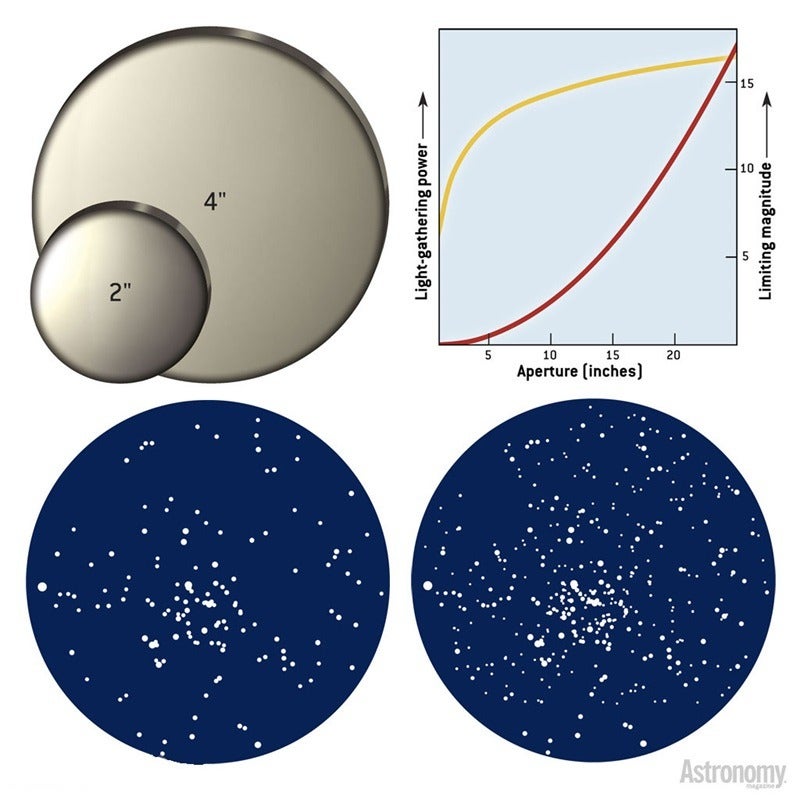

A telescope’s main purpose is to collect light. This property of telescopes allows you to observe objects much fainter than you can see with your eyes alone. Galileo said it best when he declared that telescopes “revealed the invisible.”

2. When I buy my first telescope, will it be complete, or will I have to buy additional items to make it work?

Most telescopes marketed to beginners are complete systems, ready for the sky as soon as you unpack them and perform whatever setup procedures the manufacturer recommends. Some high-end models are sold as “optical-tube assembly only” versions. This means what it says: All you’re purchasing is the optics in the tube — no mount, tripod, or accessories.

Refractors usually need a star diagonal because of their design. A star diagonal bends the light from your target object 90°, so without one, you find yourself in some awkward positions when you’re observing objects high in the sky. The star diagonal fits into the telescope’s focuser, and the eyepiece fits into the star diagonal. Most manufacturers that provide complete refractor telescopes include a star diagonal.

3. I’m interested in observing, but I don’t know which scope to buy. What should I do first?

Your first step should be to learn all you can about telescopes: what types are available, what manufacturers sell them, and what words describe them. Page through the ads in each issue of Astronomy magazine (or the stories below), and you’ll see a range of what’s available.

For each telescope that interests you, visit that manufacturer’s website. When you’re finished reading this article, refer back to recent issues of Astronomy and carefully read telescope reviews (subscribers can read them online in the Astronomy.com Equipment Review Archive). You may not understand everything discussed in each review, but you’ll get a taste of telescope terminology. By doing this, you’ll learn what’s important to observers when they use a telescope. You’ll get a feel for optical and mechanical quality, ease of use (including portability), extra features, and — perhaps most importantly — which objects the telescope excels on.

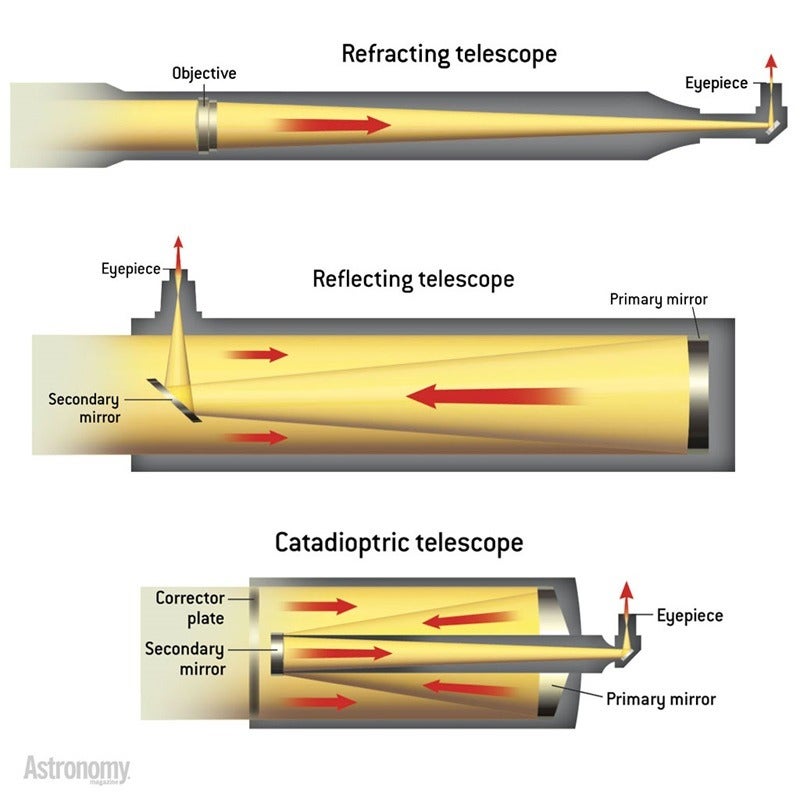

The three main types of telescopes use lenses, mirrors, or a combination of both.

Refracting telescopes use lenses — combining at least two, and as many as four, pieces of glass — as their objective (the primary light-gathering device).

Reflecting telescopes use mirrors to gather and focus light. In a Newtonian reflector — the most common type — light reflects from the primary mirror (whose surface is ground into a parabola so light comes to a common focus). The light strikes a smaller, flat secondary mirror near the top of the tube. The light then is bent 90° and enters the eyepiece through a small hole in the tube.

Catadioptric, or compound, telescopes incorporate a primary mirror coupled with a corrector lens placed at the front of the tube. The primary mirror’s curve is ground to a simple shape, usually a sphere. Ordinarily, a spherical mirror would introduce aberrations in the viewed image, but the corrector of a catadioptric scope “pre-bends” the light before it strikes the mirror. Two popular catadioptric telescopes are the Schmidt-Cassegrain and Maksutov-Cassegrain designs.

4. Is it true that I should purchase binoculars before a telescope?

No. I used to give this advice to beginning amateur astronomers, but not any more. The view through binoculars — especially from a light-polluted site — often proves disappointing to beginners. However, high-quality binoculars are a valuable observing accessory. Large star clusters look great through binoculars, as do the Milky Way’s band and the Moon.

5. What are the sizes of “small,” “medium,” and “large” telescopes?

I can’t speak for every reference to small, medium, or large telescopes — these terms are not standardized — but here at Astronomy, when we refer to a “small” scope, we specifically mean a telescope with an aperture (size of the lens or mirror) less than 4 inches. The type of scope doesn’t matter, and neither does the quality. Many small telescopes manufactured today are high-quality instruments I am proud to use.

“Medium” telescopes have apertures from 4 to 10 inches. This category is the size most amateur astronomers use. One of the most popular scopes is an 8-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain.

Finally, any telescope with a lens or mirror larger than 10 inches is “large.” More large telescopes are in use today than ever before. The introduction of Dobsonian mounts is largely responsible for this. Newtonian reflectors coupled to alt-az Dobsonian mounts (see “Telescope mounts” later in this article) dramatically reduce the prices (and weights) of large telescopes from what they would be with a motor-driven, equatorial mount..

6. I’ve heard “bigger is better” is true when it comes to telescopes. What are the real advantages of big scopes?

The larger the telescope’s diameter, the more light it will collect. A 4-inch refractor, for example, is a great scope for planets, the Moon, and double stars. I know because I own one, and I wouldn’t part with it for love or money. This size scope, however, is a bit small for deep-sky objects such as nebulae, star clusters, and galaxies.

An 8-inch telescope (it doesn’t matter what type) will move you into a new dimension of viewing. The objects you see with an 8-inch scope will reveal more detail. Keep in mind, however, that if you stay interested in observing, you’ll crave even larger scopes. This malady among amateur astronomers is known as “aperture fever.” And, yes, I’m infected. I started many years ago with a 2.4-inch telescope of good quality. I now own a 4-inch refractor and an 8-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain. Am I happy? Yes. Am I satisfied? Not even close. I now dream of a 20-inch telescope. I think you get the idea.

7. Is “achromat” different from “apochromat”? What do the words mean?

Both terms refer to the lens systems used in refracting telescopes. An achromat is a two-lens system. Apochromats also may employ two lenses, but they’re more likely to have three or four. The main difference between achromats and apochromats is the amount of what’s called “excess” color you’ll see on bright objects. Excess color is not a color that’s been added to what you’re viewing. Rather, it usually appears as a purple fringe on one edge of the object. Apochromats deliver an image essentially free of excess color.

Through an achromat, you’ll see excess color on bright objects like Jupiter, Venus, and the Moon. Many observers can ignore the excess color. Apochromats always are more expensive than comparable achromats, and usually by a sizeable amount.

8. I’ve just purchased a new telescope, and am really excited to use it. What’s the first thing I should do?

Read the operating manual several times, and set up your telescope indoors before you try to set it up outdoors at night. This will familiarize you with the location and operation of any switches, buttons, and levers. Knowing how to use your telescope before you head outdoors will enable you to use your observing time efficiently. This will be especially helpful for sessions such as the Messier marathon (locating all Messier objects in one evening).

9. Why are objects I view through my telescope upside-down?

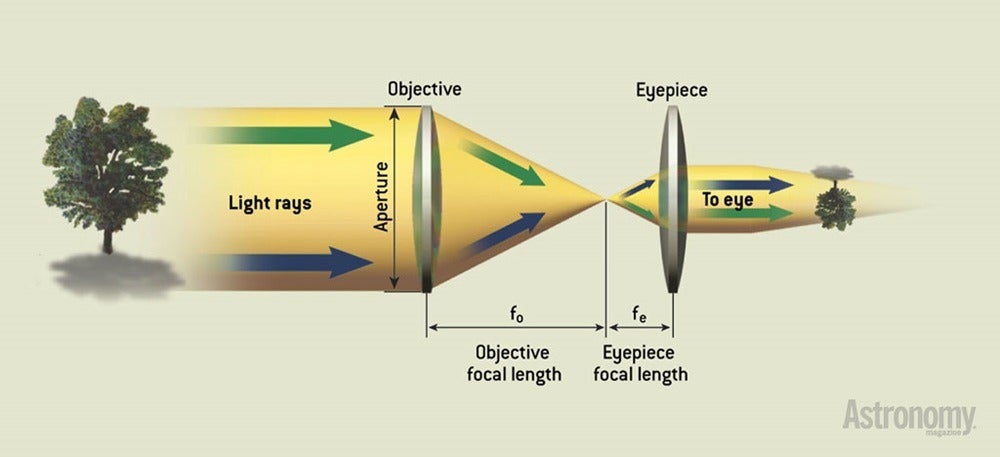

Just before the light collected by your telescope’s main lens or mirror enters the eyepiece, it’s flipped (see “Let’s talk optics” above), so you see an inverted image. A prism assembly (usually called an “image erector”) will re-flip the image, but adding this accessory will cause some light to be lost. And regarding observing, the telescope’s function is to deliver the maximum amount of an object’s light to your eye, so you don’t want to lose light from flipping the image. Besides, keep in mind there’s no up or down in space, and with most objects, you won’t even know they’re upside-down.

Let’s talk optics of telescopes

The f/4, f/10, or f/15 represent a telescope’s focal ratio (f/ratio). Focal ratio is determined by dividing the focal length (the distance from the objective to where the light comes to a focus) by the aperture. Here’s an example: A 6-inch telescope has a focal length of 36 inches. To find the f/ratio, divide 36 by 6. This produces f/6. Often, the aperture is in inches, but the focal length is given in millimeters. If so, just multiply the inches by 25.4.

To find magnification, simply divide the telescope’s focal length (fo) by the eyepiece’s focal length (fe). For example, if your telescope has a focal length of 1,000mm and you choose a 25mm eyepiece, the magnification will be 40x. Remember, magnification alone is not a good indicator of telescope quality. Magnification is determined by which eyepiece you use with any telescope. So, a low-quality scope can have a poorly made eyepiece, and the combination can give high power. But any images viewed through it will look distorted — although they will be magnified as claimed.

10. Can I use my telescope for views of earthly objects?

Absolutely! Many nighttime observers (usually those with small refractors because of size and portability issues) also use their telescopes for bird-watching or other nature-watching activities. Plus, think about pictures you’ve seen of sailors in centuries past — they almost always are at the bow looking through a telescope.

11. I would like to buy a telescope, but almost all I see are expensive. Why?

A good telescope is a combination of high-quality optics, machining, electronics, and mechanical controls. Such things aren’t cheap. It takes incredibly expensive, high-precision machinery to grind the curves into mirrors or fabricate lenses. Some lenses comprise up to four separate elements, each with two optical surfaces. And the larger the mirror or lens, the bigger and stronger the supporting tube, drive, and tripod have to be.

12. Is there any way for me to “test drive” a telescope?

Yes. Look in your area for an astronomy club, and visit one of its meetings. You’ll find others who enjoy astronomy as much as you and are willing to share information and views through their telescopes. At one of the club’s public or members-only stargazing sessions, you’ll be able to look through many different telescopes in a short period of time.

13. Apart from quality optics, what’s the most important thing in a telescope system?

The mount. You can buy the finest optics on the planet, but if you put them on an undersized or poor-quality mount, you won’t be happy with your system. No telescope can function in high winds, but a poor mount will transfer vibrations in a light breeze. The mount’s quality also affects the “damp-down” time. This is the interval between when you touch the scope (to focus, for example) and when the image in the eyepiece stops moving. Sturdy mounts reduce this to a second or two. Bad mounts increase this time to an intolerable length. Mount quality is one more reason to “try before you buy.”

14. Is a “go-to” scope better than one without go-to?

Yes. Once properly set up, a go-to scope (actually, it’s the telescope’s drive that’s go-to) will save you lots of time by moving under internal computer control to any object you select. It’s important, however, that you understand how to set up your scope, and that will require you to identify a few bright stars. Use a star chart to make this step easier. Even experienced observers prefer go-to scopes because they make star-hopping to deep-sky objects a thing of the past (when star-hopping, an observer locates a bright star and proceeds to ever-fainter stars until the target is located).

15. Since telescopes are used outside, do they need electricity?

No, but their motor (go-to) drives do. In most cases, telescope drives use direct current, which means you can either use batteries or obtain an adapter (usually you are given an option) that will allow you to plug into an electrical outlet.

3 types of telescopes

The three main types of telescopes use lenses, mirrors, or a combination of both.

Refracting telescopes use lenses — combining at least two, and as many as four, pieces of glass — as their objective (the primary light-gathering device).

Reflecting telescopes use mirrors to gather and focus light. In a Newtonian reflector — the most common type — light reflects from the primary mirror (whose surface is ground into a parabola so light comes to a common focus). The light strikes a smaller, flat secondary mirror near the top of the tube. The light then is bent 90° and enters the eyepiece through a small hole in the tube.

Catadioptric, or compound, telescopes incorporate a primary mirror coupled with a corrector lens placed at the front of the tube. The primary mirror’s curve is ground to a simple shape, usually a sphere. Ordinarily, a spherical mirror would introduce aberrations in the viewed image, but the corrector of a catadioptric scope “pre-bends” the light before it strikes the mirror. Two popular catadioptric telescopes are the Schmidt-Cassegrain and Maksutov-Cassegrain designs.

Finder scope setup

Align your finder scope during the day. Most observers take time before each observing session to check their finder scope’s alignment. Here’s how:

- Insert a low-power eyepiece in your telescope for initial alignment.

- Loosen your scope’s motion-control locks to allow movement.

- Move your telescope until you center a distant object (the top of a transmission tower, tree, building, etc.). Focus your scope to view the object.

- Lock down your telescope’s motion controls to avoid movement.

- Loosen the screw locks on your finder scope’s mounting bracket (see your telescope’s manual), and then position the finder scope so the object that’s centered in your scope also is centered in your finder.

- Lock your finder scope into position.

- For higher precision, replace the low-power eyepiece in your telescope with one that provides higher magnification, then refine the alignment.

Kinds of telescope mounts

An equatorial mount moves in two planes, with one axis pointed toward the North Celestial Pole (NCP) — a spot in the northern sky near Polaris. With an optional motor drive, you can align the mount to the NCP, and the object you are observing will stay in the field of view. If you’re planning to do long-exposure astrophotography or digital imaging, an equatorial mount is essential.

An altitude-azimuth (alt-az) mount moves the telescope horizontal and vertical. A camera tripod is a good example of an alt-az mount.

It can be difficult to tell an alt-az forkmount from an equatorial fork mount. The difference is an equatorial fork mount lines up with the NCP. Fork mounts are popular with compound scopes. You will also find the majority of modern observatories use equatorial fork mounts.

A Dobsonian mount is an alt-az type specifically made for Newtonian reflecting telescopes. The mount, which employs a swivel base and a cradle assembly to hold the telescope tube, has a simple design and is easy to construct (if you choose to build one yourself).

(Editor’s note: The following article was first published in 2014 and has been slightly updated.)