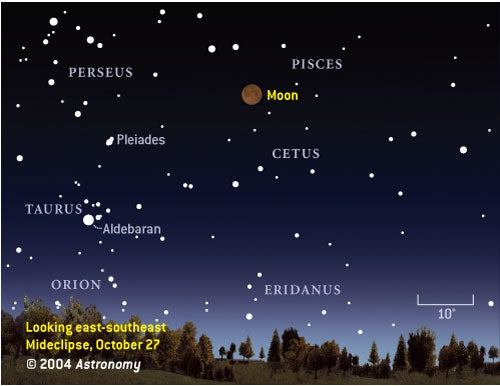

The southern half of the Moon will be darker because it passes closest to the center of Earth’s shadow. With the naked eye, some observers might be reminded of a giant, telescopic view of Mars: a bright polar cap with patchy, darker markings on the disk. Although the eclipse looks grand even from the city, it appears more impressive in a dark country sky. As the moonlight fades, the late summer Milky Way blossoms into prominence.

When the Sun, Earth, and Moon line up for a lunar eclipse, an accompanying eclipse of the Sun typically takes place 2 weeks before or after. As if receiving a consolation prize for missing lunar totality, observers with clear skies in Japan, northeastern Asia, Alaska, and Hawaii will witness a partial solar eclipse on October 13/14.

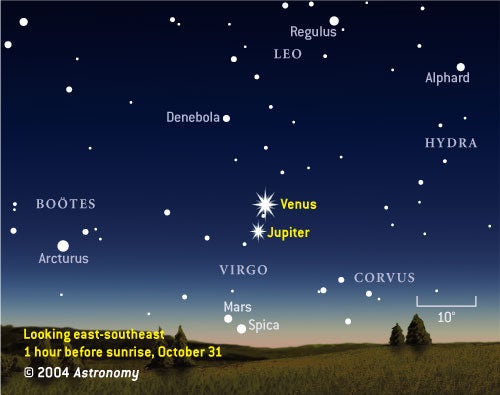

This past spring, the evening sky held a monopoly on bright planets and comets. Now, the best planetary displays occur in the morning, where Venus and Saturn hold court. By 6 a.m., Saturn lies high in the south and is perfectly placed for telescopic observation. Brilliant Venus slides past Regulus on the morning of October 3. Only half a Moon-width separates the very unequal pair (Venus gleams more than 100 times brighter than Regulus).

Unless you make an effort, it’s easy to miss a lot of activity involving the minor bodies of the solar system. Thousands of asteroids and large chunks of space rock pace around the solar system, waiting for a potential life-altering collision with another body. Luckily

for us, a potato-shaped rock a couple of miles across just misses Earth during the last week of September. See page 70 to follow the swift journey of asteroid 4179 Toutatis.

Comets may be small, typically a mile across or so, but they shed lots of dust as they round the Sun. These shrouds reflect enough light for backyard observers with modest telescopes to see them: This month, three comets come within range.

Like a broom crossing a dirty floor, Earth does its part to sweep up the dust particles littered by comets. Late on the night of October 20/21, Earth plows through part of the trail left by Comet Halley. Striking our upper atmosphere at a mind-boggling speed of more than 40 miles (66 km) per second, the dust dies a fiery death in a swift streak of light we call a meteor. A patient observer surveying the morning sky from the comfort of a lawn chair should be able to see 15 or 20 shooting stars per hour.

Far from city lights, you might see an odd glow in the east before dawn even begins. This faint glow comes from microscopic dust left over from ancient collisions among asteroids. Shaped like a pyramid with its base on the horizon, this is called the “zodiacal light” because it lines up along the constellations of the zodiac.

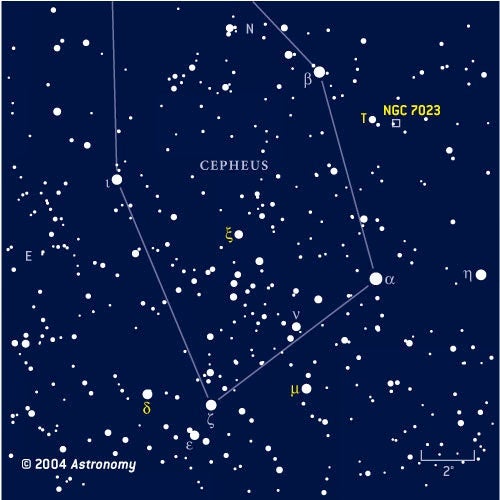

You can view Cepheus best under a dark sky far from city lights. It does not have dazzling jewels like some other Milky Way constellations, but instead shines with a quiet beauty. During a slow sweep of Cepheus, you can see brighter, colored stars floating on a vast carpet of background pinpoints. Here and there, darker fingers of obscuring gas and dust ooze in and out like waves surging softly up the beach.

Kingly stars

Delta (δ) Cephei, best known as the grandfather of Cepheid variable stars, also deserves attention as a wide double star. Delta’s brighter component glows yellow and shows a nice contrast to its fainter blue companion. Both appear readily at low power in any telescope. Be sure to take in the rich background, in many ways more beautiful than that surrounding the Cygnus doublet.

Smack in the middle of the “house” lies Xi (ξ) Cephei, a fine binary star that takes 3,800 years to complete one orbit. The 4.4- and 6.5-magnitude components appear 8″ apart, five times closer than the Delta pair. The best view comes at magnifications above 100x.

During your binocular sweep, you likely noticed a lovely orange star at the base of the house. This is Sir William Herschel’s “Garnet Star,” although calling it a shade of red seems overly enthusiastic. A much stronger shade of orange will greet your eye when you point a telescope at the long-period variable T Cephei, which crests at the maximum of its 390-day cycle this month. T Cep should glow around magnitude 6.5. Check it every 2 weeks and you’ll notice T dimming slowly.

Sweep 1° west from T Cep and you’ll land on the fascinating Iris Nebula. It was discovered October 18, 1894, by William Herschel. Before the Hubble Space Telescope captured a stunning image of this delicate reflection nebula, it was called simply by its catalog number, NGC 7023.

Nebulae come in four main flavors: emission, reflection, dark, and planetary. While planetaries result from the dying gasp of a single Sun-like star, the other three are closely related to one another. They arise from the gas and dust that abound in spiral galaxies.

In a reflection nebula, dust grains scatter starlight. As the amount of dust increases, the cloud turns distinctly blue, thanks to the same scattering effect that colors our daytime sky. When the cloud contains too much dust, starlight can’t get through, resulting in a dark nebula. An emission nebula results if the star illuminating the cloud is massive and, therefore, hot enough to produce prodigious amounts of ultraviolet light. This high-energy radiation ionizes the surrounding gas and causes it to glow.

This month’s total lunar eclipse occurs on the evening of October 27 in North and South America and on the morning of October 28 in Europe. Observers in the East and Midwest will see the entire eclipse, while West Coast viewers will witness the Full Moon rising with a small bite already taken out of its lower edge.

As the Full Moon slides slowly into Earth’s shadow, the lunar surface appears black and white. The stark shadow looks deep and black, creating a harsh contrast with the sunlit portion. Gradually, as Earth’s shadow envelops more of the Moon, subtle colors become apparent. Near the onset of totality, most of the Moon will take on an orange-red hue.

The times for the various stages of the eclipse are given below in Eastern Daylight Time. Subtract one hour to convert to CDT, two hours to convert to MDT, and three hours to convert to PDT. (Add five hours to convert to Western European Time, which puts this on the morning of October 28.) The eclipse begins when the Moon enters the light penumbral shadow at 8:06 p.m. The partial phase starts when the Moon enters the darker umbral shadow at 9:14 p.m. Totality commences at 10:23 p.m. and lasts until 11:45 p.m., with mid-totality coming at 11:04 p.m. The partial eclipse ends at 12:54 a.m., and the penumbral phase wraps up at 2:03 a.m.

The gas giants Uranus and Neptune share the stage with the eclipsed Moon, but they remain evening objects all month. Both planets can be spotted through binoculars, but if this is your first search for them this season, a star chart that reaches down to 8th magnitude will help.

Uranus resides in the faint constellation Aquarius the Water-bearer. Aquarius does contain a recognizable pattern of five stars, however, known as the “Water Jar” and consisting of Alpha (α), Gamma (γ), Pi (π), Zeta (ζ), and Eta (η) Aquarii. Uranus lies about 10° south of the Water Jar, or 1.5 field diameters in 7×50 binoculars. You’ll find a solitary, 4.8-magnitude star in the same region. This is Sigma (σ) Aquarii. Uranus lies 2° west of the star and, at magnitude 5.8, is the only other bright object in the vicinity. Through a telescope, Uranus reveals a tiny, 3.6″-diameter disk having a distinct blue-green color.

Neptune lies one constellation to the west of Uranus, in Capricornus the Sea Goat. You can find Neptune 1.3° west of 4th-magnitude Theta (θ) Capricorni. Normally, a planet’s motion from night to night will reveal its identity. However, Earth’s own orbital path now carries us almost directly away from Neptune, so its westerly motion against the starry background slows to a crawl. On October 24, Neptune appears stationary relative to the stars, then it begins to move slowly eastward. The planet glows faintly at magnitude 7.9 and, through a telescope, shows a 2.3″-diameter, blue-gray disk.

No other planets grace the evening sky, and the planetary action shifts to the early morning. Saturn appears first, rising above the east-northeastern horizon around 1 a.m. on October 1. By month’s end, Saturn rises well before midnight thanks to the one-hour change in clocks on the 31st. The ringed planet lies south of the bright twin stars, Castor and Pollux, in Gemini. A waning crescent Moon lies between Pollux and Saturn on the morning of October 7.

The next planet to rise is brilliant Venus. Shining at magnitude -4.1, it outshines every other object in the night sky except the Moon. On October 3, Venus rises around 4 a.m. and lies next to Regulus, the brightest star in Leo the Lion. This rare close conjunction places both objects within the same telescopic field of view. At their closest, only 9′ separate the pair. Regulus shines at magnitude 1.4, so the two differ by a little more than five magnitudes (a factor of one hundred) in brightness.

Throughout the month, watch Venus as it falls toward Jupiter. The giant planet rises barely before dawn in early October but climbs away from the horizon each day. By October 10, a crescent Moon lies 5° above Venus while Jupiter lies 25° below. Two mornings later, the waning Moon passes 4° above Jupiter.

Mars rises about an hour before the Sun October 31 and lies 3° north of Spica, the brightest star in the constellation Virgo. The Red Planet has begun a slow climb toward opposition late next year.

A partial solar eclipse occurs on October 13/14 and can be seen from Japan, northeastern Asia, Alaska, and Hawaii. The peak of this eclipse is visible from western Alaska on the evening of the 13th, beginning around 6 p.m. local time. An hour later, the partial phase reaches its maximum with 93 percent of the Sun eclipsed. Residents of Anchorage will witness a lovely crescent Sun as it sets. In Hawaii, the eclipse begins at 5:15 p.m. local time and the Moon covers 50 percent of the setting Sun.

The Orionid meteor shower peaks this year on the night of October 20/21. This coincides with the First Quarter Moon, which sets shortly before midnight. That means as the radiant climbs higher in the eastern sky during the early morning hours, there won’t be any moonlight to interfere with meteor viewing.

Orionid meteors result when Earth encounters the stream of debris deposited by Comet Halley during its countless trips around the Sun. The Orionids are one of two annual meteor showers, the other being the Eta Aquarids of May, that trace their origin to this famous comet. As their name implies, Orionid meteors appear to come from Orion the Hunter, in the northernmost part of that constellation. Because they radiate from a more northerly declination than do the Eta Aquarids, Northern Hemisphere observers get a much better view of the Orionids.

An observer under a clear, dark sky often can see 15 to 20 meteors per hour at the peak of the Orionids. Those in typical residential areas should expect no more than about half that number. The period of activity for the Orionid shower spans from October 2 through November 7, with much lower rates the further you stray from the peak night.

An ancient crater

One of the most recognized features on the Moon has to be Mare Tranquillitatis, famous as the landing site of Apollo 11. Connected to the southern edge of Tranquillitatis is a much smaller mare, Nectaris. And at the southern border of Mare Nectaris lies the ancient, eroded crater Fracastorius.

The northern wall of this 77-mile-wide (124 km) crater all but disappeared when molten lava flooded the crater approximately 3.7 billion years ago. The flooding almost buried the central mountain peak, and the crater’s floor appears to continue right into Nectaris. The southwestern wall of Fracastorius also appears to be breached, this time by a line of multiple craterlets that terminates in a larger secondary crater on the western wall.

The best views of Fracastorius come when the Sun rises over the region, between 5 and 6 days after New Moon. This month, that corresponds to the evenings of October 18 and 19. A few days after the Sun rises (near the time of First Quarter Moon), the Sun illuminates the crater’s entire floor. That’s a good time to search for the dozen or so tiny craters that dot the floor of Fracastorius. How many of them can you spot?

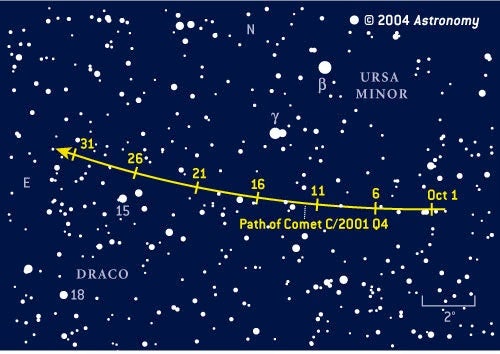

Talk about luck: In the space of less than one year, we saw three naked-eye comets and two binocular ones. Experienced observers know this kind of treat is extremely rare. In contrast, October’s comets are more typical. They require a moonless sky (which occurs near midmonth) and an observing site well outside the city for a decent view.

Six months after its lovely display, Comet C/2001 Q4 (NEAT) tracks slowly across the far north, a faint echo of its glory days when it featured a greenish head and blue ion tail. Glowing at 10th magnitude, Q4 remains visible all night near the “guardians of the pole”: Beta (β) and Gamma (γ) Ursae Minoris. Some observers mistake Beta, also known as Kochab, for Polaris because the two shine with similar intensity.

If predictions hold true, Comet C/2003 T4 (LINEAR) should approach naked-eye visibility early next year. During October, T4 slides along the tail of Draco, glowing at 12th magnitude as it accompanies Q4 in a tight circle around the pole.

Most of the bright comets that visit the inner solar system pass through only once. Yet many comets orbit the Sun on long elliptical paths, returning periodically on time scales of a few years to centuries.

Comet 78P/Gehrels comes back every 7.2 years. (The number 78 means it was the 78th comet recognized as periodic, hence the P.) At its closest approach to the Sun, Gehrels comes no closer than twice Earth’s distance from the Sun, placing it outside the orbit of Mars. This apparition is as good as it’s going to get because the comet hits peak brightness when Earth lies closest to it. Because it measures only a mile or so across and remains far from the Sun, Gehrels should reach only 11th magnitude, about the same brightness as a typical galaxy on the Messier list.

Gehrels appears best after 10 p.m., when it has risen in the east just to the right of the beautiful Pleiades star cluster. No galaxies or other deep-sky objects that could deceive you inhabit the area. This comet likely will have a bright, nearly stellar point surrounded by a circular fuzz. Its tail probably will be hidden from view, pointing behind it and away from both the Sun and Earth.

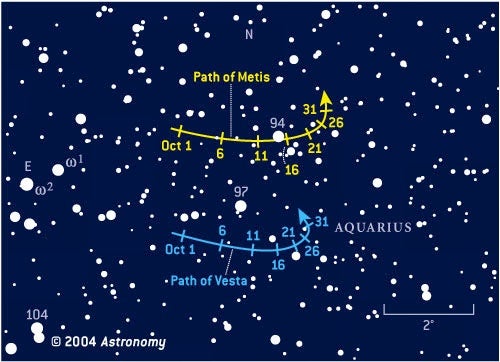

One benefit of tracking bright asteroids is that you get a chance to appreciate the extent of a constellation you otherwise might ignore. Aquarius, like its neighbor to the west, Capricornus, contains only a couple of stars readily visible from an urban backyard. Under a dark country sky, however, a beautiful, delicate outline of 4th-magnitude stars adorns Aquarius.

Grab your binoculars and slide two fields of view north of Fomalhaut, the sparkling bright star that appears by itself low on the southern horizon. You’ll land on 97 Aquarii, the lone bright star in a half-circlet of wide doublets and triplets that forms the bottom end of Aquarius.

Asteroid 4 Vesta will be the next brightest object just below 97 Aqr, glowing at magnitude 6.7. If you return every two or three nights, you will notice the asteroid’s telltale displacement against the background stars. Vesta reached opposition in September, so it now appears highest in the south during late evening.

As a challenge, see if you can spot 9 Metis, Vesta’s faithful traveling companion these past few months. Metis lies just over 2° north of Vesta but glows considerably fainter at magnitude 9.7.