He guided the gaze of the world’s largest refracting telescope in the direction of Orion, targeting a mysterious object he’d tried to glimpse many times since his comet-hunting days decades earlier. Other astronomers had previously photographed the area, but the nature — and very existence — of one fuzzy spot remained controversial.

On this picturesque Wisconsin night, however, there was no mistaking it: A crisp, black silhouette stood out against a bright background sky.

“From the view, one would not question for a moment that a real object — dusty looking, but very feebly brighter than the night sky — occupies the place,” Barnard wrote. “This object has not received the attention it deserves,” he added.

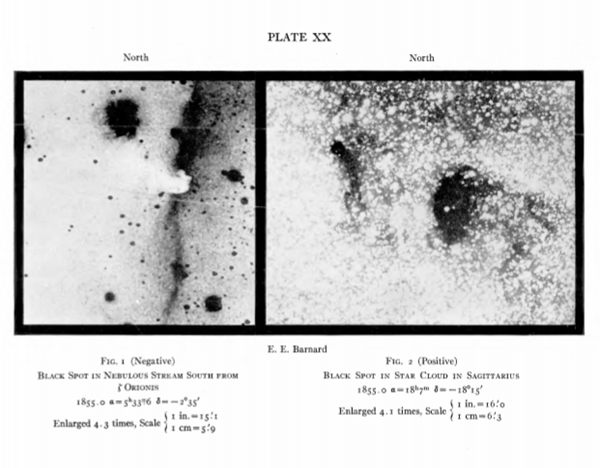

Barnard also managed to capture a picture of the celestial object, which is still recognizable to space fans today. He had finally tamed the Horsehead Nebula, an object whose fame has since grown, spurred by an era of multi-billion-dollar space telescopes and advanced instruments for amateur astronomers.

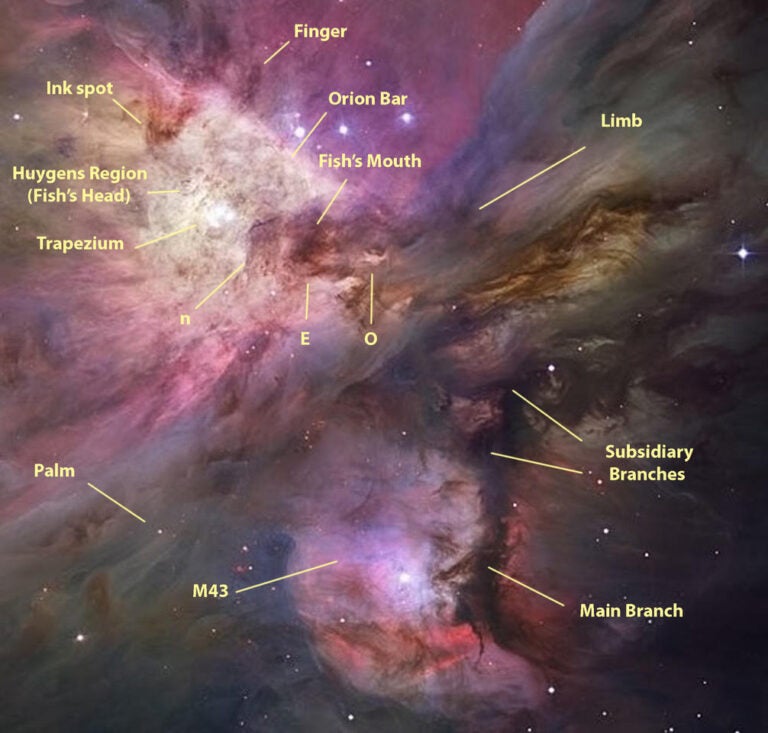

The Horsehead Nebula, also known as Barnard 33, and its companion, the Flame Nebula, sit near the star Alnitak in Orion’s Belt. Today, we know that the Horsehead is a dark, light-gobbling nebula made of cold gas and dust. And, as Barnard showed, this dark cloud’s signature shape is only visible because its silhouette obscures the light from the brighter nebula behind it.

The horse’s prominent “jaw” is actually shaped by intense radiation from a nearby star blowing on the dark cloud. And as easy as it is to focus on this charismatic object, the Horsehead Nebula is just one piece of the much larger Orion Molecular Cloud Complex. This star forming region spreads across hundreds of light-years and covers much of the Orion constellation itself. And by studying it, astronomers have learned the stellar nursery has already given birth to young stars, some even with protoplanetary disks.

Its characteristic shape and vivid pink colors have made the Horsehead Nebula a tempting telescopic target for many years. But despite its popularity, the gas cloud is actually very faint.

The Horsehead Nebula sits a good distance from Earth — some 1,500 light-years away. As a result, it shines at just magnitude 6.8. To make matters even worse, there’s usually a relatively bright star in the same field of view. So, through a telescope eyepiece, the horsehead appears dim, small, and a bit washed out.

But because the Horsehead Nebula is so hard to spot, some amateur astronomers use it to their observing skills. That’s partly why, when this gas cloud was first spotted, its signature shape wasn’t even noticed.

How the Horsehead Nebula was discovered

The discovery story of the Horsehead Nebula is surprisingly muddled, especially for an object that’s so famous today. A number of astronomers stumbled across it over the years, but their limited instruments made it hard to carry out detailed studies.

The British astronomer William Herschel, discoverer of Uranus, may have been the first to see the Horsehead Nebula through a telescope. Herschel was a prolific observer and, in 1811, he submitted a paper boldly titled “The Construction of the Heavens” to the journal Philosophical Transactions. In one section, he laid out 52 different nebulous objects that he’d spotted in the night sky over his lifetime.

“They can only be seen when the air is perfectly clear, and when the observer has been in the dark long enough for the eye to recover from the impression of having been in the light,” Herschel wrote.

However, his descriptions of the objects themselves were frustratingly vague. They went largely ignored for nearly 100 years.

That’s when Welsh amateur astronomer Isaac Roberts decided to photograph the 52 locations Herschel mentioned. It took him six years to complete the task, and in a paper published in 1902, Roberts presented a largely critical take on the existence of Herschel’s nebulous targets.

There were a few objects that clearly stood out though. And one of the locations was a dead ringer for the location of the Horsehead Nebula, which Roberts managed to capture in a photograph. However, Roberts’ view was too faint to make out much detail. He went on to dismiss it as a mere “a stream of nebulosity.”

Meanwhile, around the turn of the century — and seemingly unbeknownst to many in the field, or simply left out of their publications — another astronomer had already discovered the object in her growing catalog.

Cutting edge science to desktop wallpaper

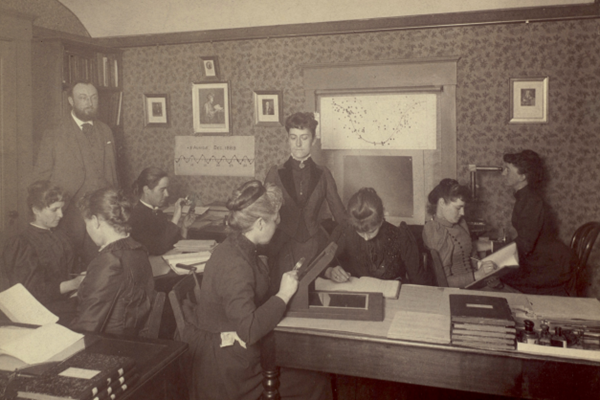

Williamina Fleming was a human “computer” employed by the Harvard College Observatory more than a century ago. The Scottish astronomer started her career as a maid in the home of Edward Charles Pickering, the observatory’s director. But she was soon hired to analyze stellar spectra — the chemical fingerprints of stars. Fleming’s system of classifying stars grew in popularity, and astronomers still use today.

Throughout her career, Fleming cataloged thousands of objects — and one of those was the Horsehead Nebula. In 1888, she was reviewing one of Pickering’s photographic plates when she spotted the nebulous object.

To her, it was simply one more nebulae out of the myriad other objects she cataloged during her lifetime. But, Fleming still gets credit for the first confirmed discovery of the Horsehead Nebula.

Even early popular references don’t seem to agree on what to call it. In 1922, a book called Astronomy for Young Folks referred to it as the “Dark Horse Nebula.” But the more familiar “Horsehead Nebula” was also common vernacular for astronomers during the early 1920s. However, the latter term came to dominate soon after, as more and more astronomers were able to capture detailed photographs of it.

By the dawn of the Space Race, the Horsehead Nebula was a favorite in astronomy books, magazines, and works of science-fiction.

Today, the Horsehead Nebula appears far more often in desktop wallpapers than it does in scientific papers. But that hasn’t stopped people from appreciating its beauty. Space fans all over the world love the charismatic cosmic equine. And its highly doubtful that’s going to change anytime soon.