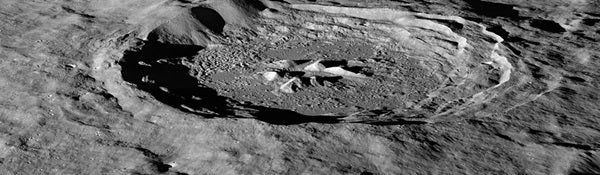

Recent observations by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) spacecraft indicate that these deposits may be slightly more abundant on crater slopes in the southern hemisphere that face the lunar south pole. “There’s an average of about 23 parts-per-million-by-weight (ppmw) more hydrogen on pole-facing slopes (PFS) than on equator-facing slopes (EFS),” said Timothy McClanahan of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

This is the first time a widespread geochemical difference in hydrogen abundance between PFS and EFS on the Moon has been detected. It is equal to a 1 percent difference in the neutron signal detected by LRO’s Lunar Exploration Neutron Detector (LEND) instrument.

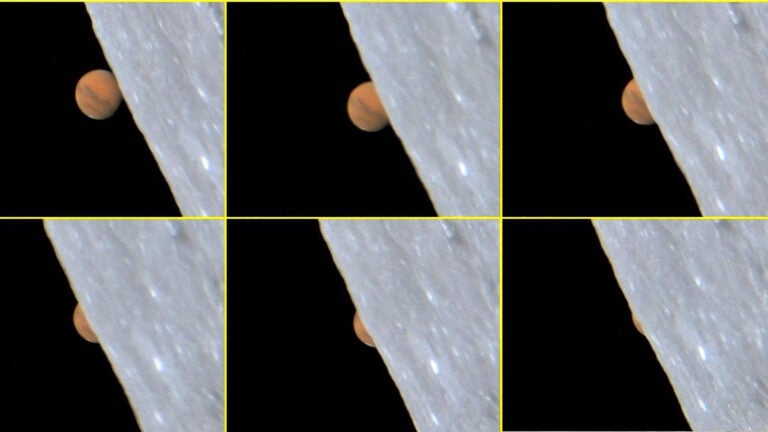

The hydrogen-bearing material is volatile — easily vaporized — and may be in the form of water molecules — two hydrogen atoms bound to an oxygen atom — or hydroxyl molecules — an oxygen bound to a hydrogen — that are loosely bound to the lunar surface. The cause of the discrepancy between PFS and EFS may be similar to how the Sun mobilizes or redistributes frozen water from warmer to colder places on Earth’s surface, said McClanahan.

“Here in the Northern Hemisphere, if you go outside on a sunny day after a snowfall, you’ll notice that there’s more snow on north-facing slopes because they lose water at slower rates than the more sunlit south-facing slopes” said McClanahan. “We think a similar phenomenon is happening with the volatiles on the Moon — PFS don’t get as much sunlight as EFS, so this easily vaporized material stays longer and possibly accumulates to a greater extent on PFS.”

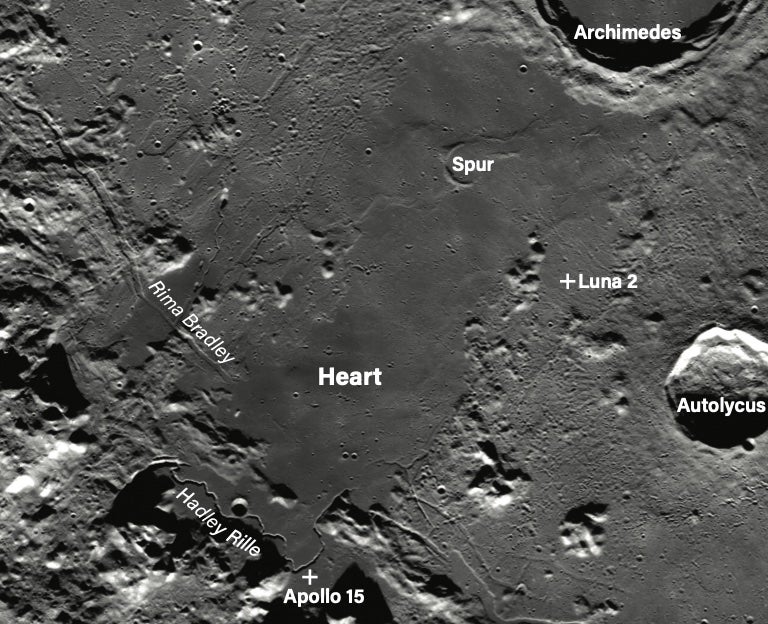

The team observed the greater hydrogen abundance on PFS in the topography of the Moon’s southern hemisphere, beginning at between 50° and 60° south latitude. Slopes closer to the south pole show a larger hydrogen concentration difference. Also, hydrogen was detected in greater concentrations on the larger PFS, about 45 ppmw near the poles. Spatially broader slopes provide more detectable signals than smaller slopes. The result indicates that PFS have greater hydrogen concentrations than their surrounding regions. Also, the LEND measurements over the larger EFS don’t contrast with their surrounding regions, which indicates EFS have hydrogen concentrations that are equal to their surroundings, according to McClanahan. The team thinks more hydrogen may be found on PFS in northern hemisphere craters as well, but they are still gathering and analyzing LEND data for this region.

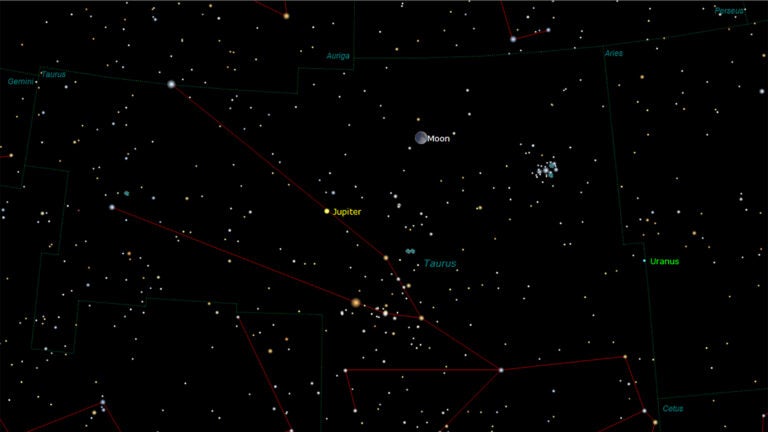

There are different possible sources for the hydrogen on the Moon. Comets and some asteroids contain large amounts of water, and impacts by these objects may bring hydrogen to the Moon. Hydrogen-bearing molecules also could be created on the lunar surface by interaction with the solar wind — a thin stream of gas that’s constantly blown off the Sun. Most of the solar wind is hydrogen, and this hydrogen may interact with oxygen in silicate rock and dust on the Moon to form hydroxyl and possibly water molecules. After these molecules arrive at the Moon, astronomers think they get energized by sunlight and then bounce across the lunar surface — they get stuck, at least temporarily, in colder and more shadowy areas.

Since the 1960s, scientists thought that only in permanently shadowed areas in craters near the lunar poles was it cold enough to accumulate this volatile material, but recent observations by a number of spacecraft, including LRO, suggest that hydrogen on the Moon is more widespread.

It’s uncertain if the hydrogen is abundant enough to economically mine. “The amounts we are detecting are still drier than the driest desert on Earth,” said McClanahan. However, the resolution of the LEND instrument is greater than the size of most PFS, so smaller PFS slopes, perhaps approaching yards in size, may have significantly higher abundances, and indications are that the greatest hydrogen concentrations are within the permanently shaded regions, said McClanahan.

The team made the observations using LRO’s LEND instrument, which detects hydrogen by counting the number of subatomic particles called neutrons flying off the lunar surface. The neutrons are produced when the lunar surface gets bombarded by cosmic rays. Space is permeated by cosmic rays, which are high-speed particles produced by powerful events like flares on the Sun or exploding stars in deep space. Cosmic rays shatter atoms in material near the lunar surface, generating neutrons that bounce from atom to atom like a billiard ball. Some neutrons happen to bounce back into space where they can be counted by neutron detectors.

Neutrons from cosmic-ray collisions have a wide range of speeds, and hydrogen atoms are most efficient at stopping neutrons in their medium speed range, called epithermal neutrons. Collisions with hydrogen atoms in the lunar regolith reduce the numbers of epithermal neutrons that fly into space. The more hydrogen present, the fewer epithermal neutrons the LEND detector will count.

The team interpreted a widespread decrease in the number of epithermal neutrons detected by LEND as a signal that hydrogen is present on PFS. They combined data from LEND with lunar topography and illumination maps derived from LRO’s Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter (LOLA) and temperature maps from LRO’s Diviner instrument (Diviner Lunar Radiometer Experiment) to discover the greater hydrogen abundance and associated surface conditions on PFS.

In addition to seeing if the same pattern exists in the Moon’s northern hemisphere, the team wants to see if the hydrogen abundance changes with the transition from day to night. If so, it would substantiate existing evidence of an active production and cycling of hydrogen on the lunar surface, said McClanahan.