The classic Moon illusion — that it appears larger when seen near the horizon than when overhead — is both a personal and complicated affair.

It’s personal because not everyone notices it; some can’t see it even if you point it out to them. It’s complicated because for those who do see it, the reasons why this psychological phenomenon occurs are vast: the perceived shape of the sky, the direction of our gaze, the influence of nearby objects on our distance estimates, atmospheric refraction, framing effects, and linear perspective, to name but a few. Now I’d like to add another dimension to this already perplexing affair.

Bad Moon rising

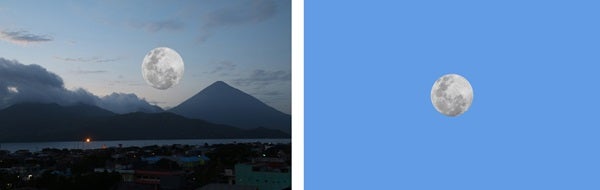

This past August 15, I watched the 13-day-old gibbous Moon rise above a distant horizon lined with houses and trees. The Moon loomed large in my mind’s eye, and I chalked it up to the Moon illusion. When I looked again around sunset, our satellite, as expected, appeared noticeably smaller midway up the sky. What I didn’t expect was that about an hour later, the disk had swollen once again — though not to the size it was at the horizon. So I spent the next few nights leading up to Full Moon watching for this unusual event. It happened repeatedly.

It didn’t take long for me to realize what was going on. Most people enjoy looking for the Moon illusion around the time of Full Moon. When the Full Moon rises, the sky is already on its way to becoming dark; we never do get to see a Full Moon midway up the sky in the daylight or twilight.

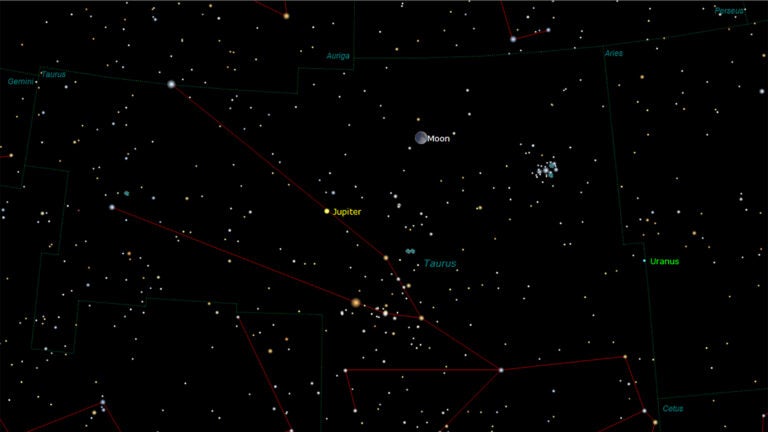

A waxing gibbous Moon, however, rises in the daylight, lies midway up the sky during twilight, and stands even higher in the dark of night. Thus we get to see the gibbous Moon against three different backgrounds, which can affect how our mind’s eye sees it.

Irradiation effect

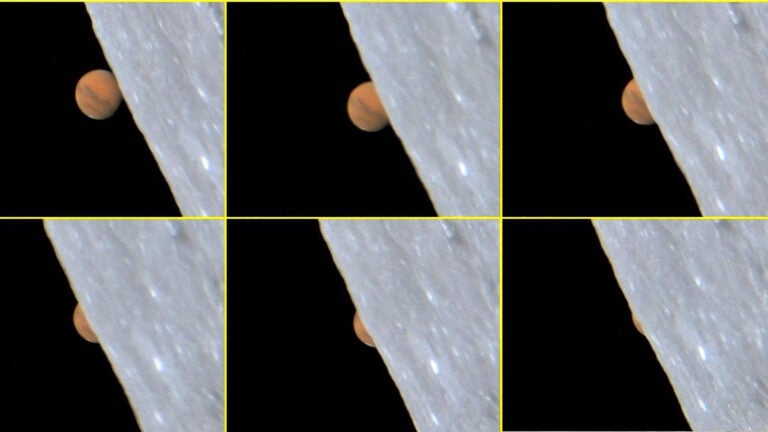

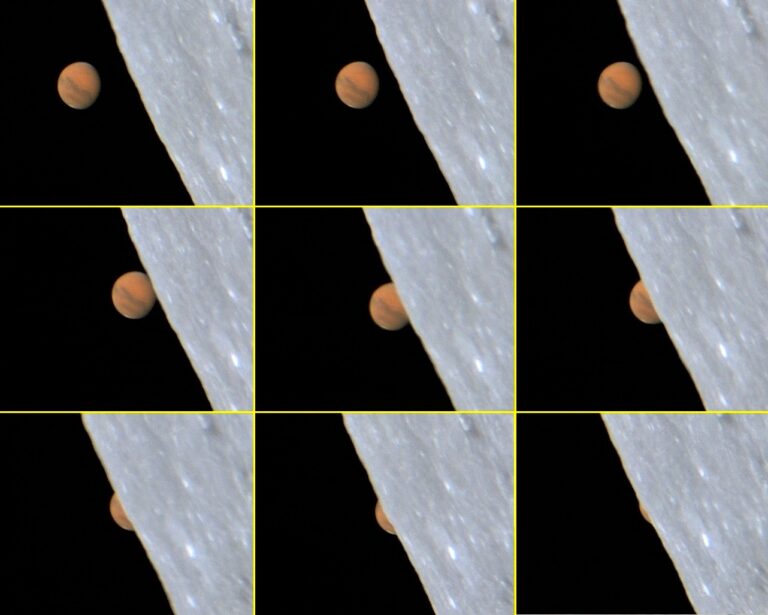

When the gibbous Moon rises, it appears largest on or near the horizon (as per the classic Moon illusion). When it is midway up in the sky during twilight, it seems to shrink. But when it rises higher still during the night, it appears to swell once again because it now appears brighter than it did in the twilight. So, it pulses.

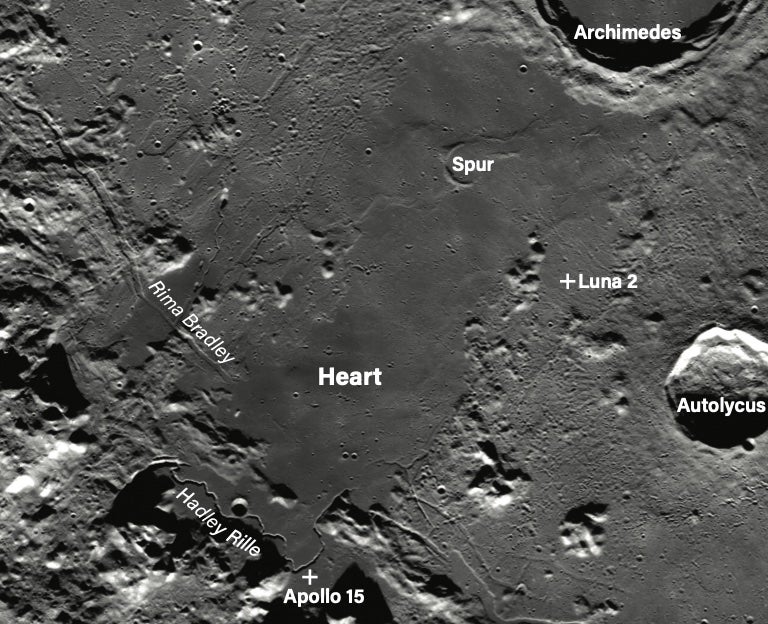

In the 19th century, German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz noticed that a light-colored object on a dark background appears larger than a dark object on a light background, and this gibbous Moon illusion appears to be related. We see a similar effect during young Moons, when the illuminated crescent appears to have a larger diameter than the remaining dark gibbous shape lit by earthshine. But only recently have neuroscientists discovered why.

In the February 10, 2014, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Jose-Manuel Alonso, a neuroscientist at the State University of New York, and colleagues said that the answer lies in the way neurons in the visual system respond to light and dark stimuli. In essence, neurons that respond to dark objects create an accurate portrayal of the object’s shape and size. But neurons responding to light objects distort the image, making them appear larger.

So, a bright Moon seen against the dark of night will appear larger than the same Moon seen in a low-contrast environment. This distortion in vision may have originated with the first cells that convert light into biochemical electrical impulses and helped our ancestors see better at night.

If you observe the Moon illusion at other times than Full Moon, I’d love to hear about it. Send your thoughts to sjomeara31@gmail.com.