The 19th-century Irish astronomer John Birmingham called attention to this curiosity in his “The Red Stars: Observations and Catalogue,” published in the 1879 Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy. Aside from his own plentiful observations, the catalog incorporated those of Danish astronomer Hans Schjellerup (who had compiled a catalog of red stars in 1866) and others, for a total of 658 red and orange stars.

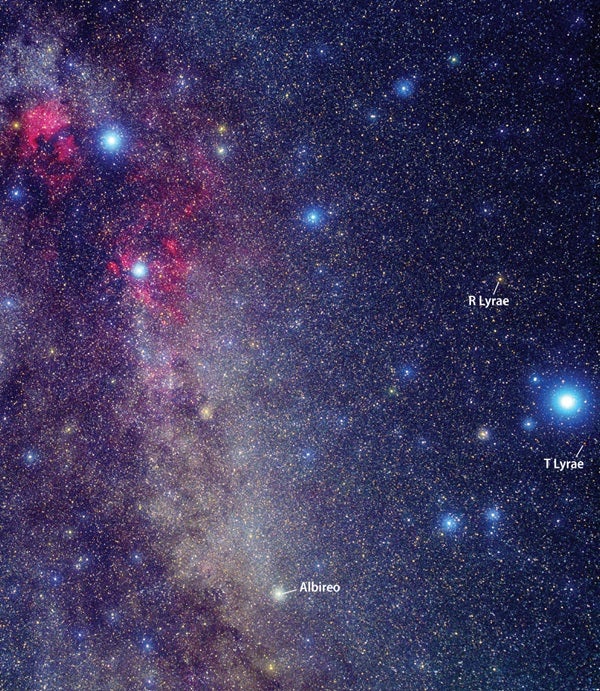

In the introduction, Birmingham notes that a “space of the heavens including the Milky Way, between Aquila, Lyra, and Cygnus, seems so peculiarly favored by red and orange stars that it might not inaptly be called the Red Region.”

In September, the Red Region luckily lies well above the southern horizon after sunset. This month I’ve spotlighted a select group of its colored gems. To help tune your color sensitivity, I’ve chosen stars that warm sequentially through the following spectral classes: G (yellow), K (orange), M (red), and the rare carbon class C (deep red). Astronomers further subdivide these classes from 0 to 9; a G8 star, for instance, looks closer to orange than yellow, and a K5 star is midway between orange and red. But what color you see is unknown – until you look.

Everyone sees color differently, so don’t rely on the star’s spectral type for a definitive visual hue. Consider the striking, colorful double star Albireo (Beta [ß] Cygni) in Cygnus. Observers have described its magnitude 3.1 K3 primary as yellow, topaz, gold, and orange; its magnitude 5.1 type B9 (blue-white) secondary (34″ away) can appear deep-blue, azure, sapphire, or green.

Perceived color is not only highly subjective, but it can also be a product of physiological and psychological effects (such as strong contrasting colors, as in the case of a double like Albireo). Star color also depends on atmospheric conditions: Dust and pollutants will redden a star’s hue. Also, stars close to the horizon will appear redder than those higher in the sky, just like the Sun does at sunset.

We’ll begin our search with magnitude 4.4 Sham, the Alpha (a) star of Sagitta the Arrow. To me, Sham (G1) has a lemon-yellow sheen. The color becomes even more conspicuous when I compare it to that of the similarly bright G8 star Beta Sagittae, which lies only 35′ to the south-southeast. Both Sham and Beta are yellow giants. But when I look at Beta through binoculars, its color appears a tad warmer, like that of a squash. Can you detect a difference?

Now lower your gaze about 10° to magnitude 0.8 Altair in Aquila the Eagle. Two colorful naked-eye companions flank Altair: magnitude 3.7 Alshain (Beta Aquilae), 2.7° to the south-southeast; and magnitude 2.7 Tarazed (Gamma [? ] Aquilae), 2° to the northwest. All three stars fit comfortably in the same binocular field of view. While spectral type A Altair shines like a sparkling blue-white diamond, I find Alshain (G8) has a banana-peel yellow hue and Tarazed (K3) has more of a golden sheen.

Note that Alshain and Beta Sagittae have the same spectral characteristics, as do Tarazed and Albireo’s brighter component. Do the stars of the same spectral type appear the same color to you? I find Beta Sagittae looks slightly deeper yellow than Alshain; it’s hard for me to discern any difference between Tarazed and the yellow star in Albireo.

Now return to Sagitta and look at magnitude 3.5 Gamma, the tip of the celestial Arrow. One of the sky’s few naked-eye red giants, it used to be classified as a K5 star, but now it’s listed as a type M0 giant. Gamma’s light appears deeper than Beta Sagittae’s through binoculars, closer to a pumpkin’s color.

Next, look at variable star R Lyrae, about 6° northeast of Vega. Also known as 13 Lyrae, it is a naked-eye red giant of spectral class M5. The star fluctuates in brightness – between magnitude 3.9 and 5.0 – over a period of 46 days, so it never dips below naked-eye visibility. Through 10×50 binoculars, I find the star has a rich orange hue.

Through a telescope, however, R Lyrae’s color seems to pale. Indeed, the 19th-century British astronomer Admiral William Henry Smyth (who had a penchant for seeing exotic star colors through his telescope) recorded R Lyrae as appearing “bright yellow.” In his own observations of red stars, Julius Schmidt (1825-1884), director of Athens Observatory, noticed that red variable stars grow paler as they increase in magnitude and become more ruddy as they again decrease toward their minimum. Birmingham also noted the same phenomenon. Watching these stars pulsate over time is like watching a leaf change colors in the fall.

Finally, turn your telescope to demon-red T Lyrae, a rare type of red giant variable star rich in carbon (it is, in fact, a carbon star), whose compounds absorb blue light effectively. T Lyrae is classified as a C6,5 star: The first number refers to the star’s temperature on a scale of 0 to 9, with 9 being at the cool end; the second number refers to how red the star appears on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the reddest. T Lyrae is, in fact, one of the reddest stars in the sky. When brightest, it shines at magnitude 7.5; when faintest, it’s at magnitude 9.3, so a telescope is best for watching its irregular pulsations.

As always, share your observations with me at someara@interpac.net.

Read “Tour the sky’s reddest stars” from Astronomy‘s December 2007 issue.

August 2010: Uranus: The Alice in Wonderland world

See an archive of Stephen James O’Meara’s Secret Sky