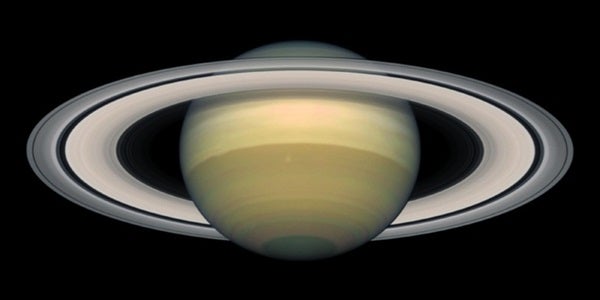

To find Saturn, look east in the late evening for the bright “star” with a steady yellow glow. Bump up the magnification as much as possible while still getting a clear, steady view. Saturn really comes to life this month because the planet casts a shadow onto the rings, giving the system an unmistakable three-dimensional appearance.

A 2-inch scope reveals a starlike dot outside the rings, but it’s more than what meets the eye. This is Saturn’s moon, Titan, the second-biggest moon in the solar system. During a 2-week period, you can watch this nearly Mars-sized moon complete an orbit of its beautiful home world.

If you’re a keen observer, set your alarm for an hour before dawn — the remainder of the bright planets put on quite a show for early risers. You can’t miss Jupiter and Venus paired low in the east. Blazing white Venus is descending slowly from her throne as the morning star and will pass one Moon-width above Jupiter November 4. The sight of the two brightest planets next to each other will be well worth the effort to get up early. Jupiter appears the fainter of the two, but it still shines brightly with a steady, light-peach hue.

Below the two planets and tucked against the horizon, you’ll find the blue-orange pair of Spica and Mars. Mars currently lies on the far side of the Sun from Earth, so it appears tiny and faint, no rival for the stellar sparkle of Spica.

The month’s top event happens the morning of November 9, when the Moon swallows Jupiter. This occultation takes place in broad daylight, around 11 a.m. EST, so take your telescope to work if you want to watch. An 8-inch scope will reveal the four bright jovian moons as well. Unless you’re really lucky, such events are rare. Observers east of the Mississippi River have a chance to see Jupiter occulted both this month and next, but people in California won’t get to see this happen until 2016.

If you live in parts of Australia or New Zealand, you’ll miss the Jupiter event but get a bigger prize: The Moon occults Venus on the morning of the 10th and then, one day later, passes in front of Mars.

The roar of the Leonid meteor shower these past few years has settled down to its more typical purr. If you’re new to meteor observing, you may want to wait until next month’s more active Geminid shower. At the peak of this year’s Leonids — shortly before dawn Wednesday, the 17th — expect about 10 shooting stars per hour.

It probably won’t come as a big surprise, but when seen through a small telescope, a planetary nebula often looks a lot like a planet. In the 1700s, Charles Messier cataloged the first few of these celestial puffballs. Then along came William Herschel, the godfather of deep-sky observers. Only 1 year after his 1781 discovery of Uranus, which appeared as a small, round, greenish disk in his 6-inch reflector, he began sweeping up other small, round disks. Their similar size, shape, and color to the newest planet made their classification obvious: planetary nebulae.

The first object in this new category was the Saturn Nebula in Aquarius. In Herschel’s own words, it appeared “very bright, nearly round, planetary, not well defined disk. 25 arcseconds.” For comparison, the ball of Saturn appears some 15″ to 20″ across from Earth.

With a scope 8 inches in aperture or less, you’ll see the Saturn Nebula just like Herschel did. Interestingly, neither Herschel nor his son John, also a high-caliber observer, saw the tendrils that are still referred to by their Latin name, “ansae.”

In 1849, using his “Leviathan” telescope, Lord Rosse first saw these extensions sticking off opposite edges of the disk and named the object the Saturn Nebula. Today, with a high-quality eyepiece on a well-made 10-inch telescope (a mere tip of the hat to Rosse’s massive, 6-foot-wide mirror), you can begin to see the ansae at powers above 200x.

In the 1880s, after thousands more deep-sky objects had been discovered, astronomer John Dryer compiled a huge reference called the New General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars, or NGC. The Saturn Nebula made it at number 7009, where it earned three exclamation marks in its brief description.

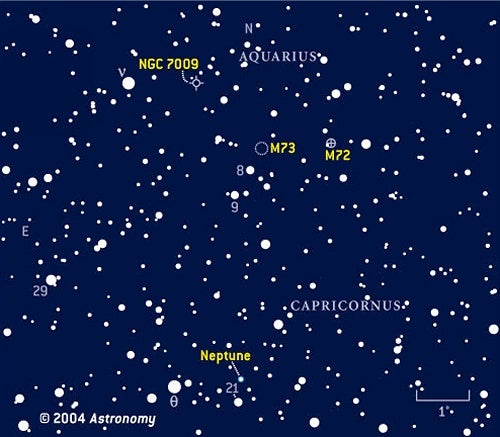

After viewing the nebula, aim your scope 6° to the south and have a look at Neptune. This real planet has the same brightness, 8th magnitude, as the nebula but appears almost a factor of 10 smaller through the eyepiece. Bump the power past 150x and look for a “fat” star, and you’ll see the planet’s tiny, blue-gray disk.

A planetary nebula forms at the end of a Sun-like star’s life. As the star exhausts its nuclear fuel, it swells to become a red giant and eventually sheds its outer layers. The stellar core contracts into a white dwarf, which emits lots of ultraviolet radiation. This energetic radiation ionizes the atoms in the surrounding cocoon, and they glow with specific colors. (This means they respond well to nebula, or “light pollution,” filters.) Many planetaries have a high surface brightness, so they can punch through a city’s veil of light pollution or the glare from a Full Moon.

A quaint pair

Most observers describe well-known deep-sky objects with superlatives, but the wide pair of M72 and M73 belongs in a class by itself — and not a higher class. M72 is a distant globular cluster, while M73 is simply a group of four stars.

Tucked away among the rich but faint starfields of western Aquarius, M72 lies just 3° southwest of the Saturn Nebula. It shows up in a low-power, rich-field telescope as a small, fuzzy cotton ball glowing at magnitude 9.3. A 6-inch scope at high power from a dark site will pick up a few of the cluster’s red giants, giving it a granular appearance.

Pan 1° east of the globular and you’ll find M73. At times, this object dissolves into the background. It consists of four stars, glowing between magnitudes 10 and 12, in a triangular shape. Through his relatively primitive telescope, Messier saw it as “a cluster of 3 or 4 small stars which resembles a nebula at first sight, containing a little nebulosity.” The superior optics of today’s scopes reveal no trace of nebulosity.

Innermost Mercury reaches greatest eastern elongation November 20, although it will not be easy to find. It lies on a part of the ecliptic — the apparent path of the Sun and planets across our sky — that currently forms a shallow angle to the western horizon after sunset. Although Mercury lies 22° from the Sun at greatest elongation, it appears only 5° above the southwestern horizon half an hour after sunset.

It shines brightly, however, at magnitude -0.3, so sharp-eyed observers will find it if they have a clear, flat horizon toward the southwest.

Once Mercury sets, turn your attention to Uranus and Neptune. You’ll need binoculars or a telescope to spy Neptune, and a star map that reaches at least 8th magnitude to home in on its location. (See page 63 for a finder chart showing the planet’s position in mid-November.)

Neptune lies near the center of the inconspicuous constellation Capricornus, which hangs in the south as darkness falls. The challenge for many of us is that few of the guide stars in Capricornus can be seen from a street-lit neighborhood. But don’t despair. A pair of 3rd-magnitude stars usually shows up. Algedi (Alpha [α] Capricorni) and Dabih (Beta [β] Cap) lie five Moon-widths apart in the constellation’s northwestern corner. From there, slide southeast until you reach 4th-magnitude Theta (θ) Cap in the north-central part of the group. Then use the finder chart to locate Neptune west-northwest of Theta. The planet glows at magnitude 7.9 and shows a 2.3″-diameter, blue-gray disk through a telescope.

Uranus proves to be an easier target because it’s brighter and lies higher in the evening sky. Glowing at magnitude 5.8, the planet pops into view in binoculars, even from moderately light-polluted sites. Look for it in Aquarius the Water-bearer nearly due west of Sigma (s) Aquarii and south of Theta Aqr. The planet stays nearly fixed relative to the background stars during the month. Through a telescope, Uranus displays a disk 3.5″ in diameter sporting a distinct blue-green hue.

Beautiful Saturn stands clear of the eastern horizon by 11 p.m. local time in early November. On the 3rd, a gibbous Moon rises with Saturn, separated by 7°. The two stage a repeat performance November 30, when they rise together around 8 p.m. This time, the two appear 5° apart.

Saturn lies in Gemini the Twins south of the two 1st-magnitude stars, Castor and Pollux, that dominate the constellation. Saturn appears noticeably brighter than both of them at magnitude 0.0. The rings, recently photographed in remarkable detail by the Cassini spacecraft, show up easily from Earth in any telescope. The dark and relatively empty Cassini Division separates the outer A ring from the brighter B ring. A good 6-inch or larger scope might reveal the dusky, innermost C ring.

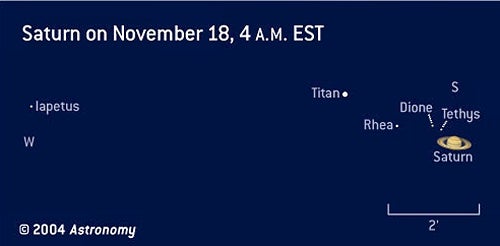

Most telescopes also show a number of moons surrounding Saturn. The brightest is Titan, which glows at magnitude 8.3. The Cassini spacecraft flies past this moon both October 26 and December 13. Earthbound observers can spot Titan most anytime, although it’s easier to pick out when it passes due north or south of the planet. The moon lies north of Saturn November 12/13 and 28/29 and south November 4/5 and 20/21.

A number of smaller moons closer to Saturn scurry around the planet like fireflies. Faintest is the innermost major moon, Mimas, which glows at magnitude 12.9. Enceladus, a February 2005 target of the Cassini spacecraft, glows one magnitude brighter. Three 10th-magnitude moons — Tethys, Dione, and Rhea, in order of increasing distance from Saturn — can be seen in almost any telescope.

Enigmatic Iapetus reaches greatest western elongation November 17/18, when it glows its brightest, magnitude 10.1. One hemisphere of Iapetus reflects lots of light while the other appears dark, so the moon’s brightness fluctuates as it orbits the planet. Iapetus passed north of Saturn at the end of October and spends the first 2 weeks of November brightening as it heads toward western elongation. It orbits far from Saturn, appearing almost 10′ (about 13 ring diameters) from the planet at its brightest.

Watch during November’s first week as Venus slides past Jupiter. For North American observers, the two appear closest the mornings of November 4 and 5. On the 4th, observers on the West Coast will see Venus standing 0.7° above Jupiter an hour before sunrise. The following morning, November 5, East Coast observers will see the pair side by side and slightly closer, with 0.6° separating them. Every morning thereafter, Venus continues to fall toward the horizon relative to Jupiter, and their separation increases by about a degree per day.

During daylight November 9, observers east of a line from Saskatchewan to Florida will see a thin crescent Moon pass in front of Jupiter. In Boston, the occultation starts at 11:06 a.m. EST with the pair high in the southwest. Residents of Atlanta will see Jupiter disappear at 11:24 a.m. EST, while those in Chicago will see the event begin at 9:57 a.m. CST. Visit the International Occultation Timing Association (IOTA) web site for times at other locations. Set up at least half an hour before the event to make sure you can locate the Moon and Jupiter.

Mars makes a brief appearance in the eastern sky before dawn. Although still far from Earth and not particularly prominent, Mars has begun its long trek to a nice opposition in late 2005. On November 30, the Red Planet stands 3° below Venus in the growing twilight. Mars appears as a moderately bright, ruddy “star” shining at magnitude 1.7.

Recent years have shown enhanced activity for the Leonid meteor shower, but none is predicted for this year’s return. The shower peaks the morning of November 17, and reduced numbers can be seen from November 14-21. Observers may catch a meteor every few minutes under the best conditions. However, following the storm-level rates in recent years, the actual number is hard to predict and could be high for certain regions of the world. Best views of the shower come once the radiant — located in the constellation Leo the Lion — has climbed high in the sky, after 3 a.m. Fortunately, the waxing crescent Moon sets well before midnight November 16.

The minor northern Taurid meteor shower peaks November 11/12. Because this is the same day as New Moon, conditions couldn’t be better. The shower and its cousin, the southern Taurids (which peak November 4/5), derive from debris left behind by Comet 2P/Encke, the comet with the shortest known period. The radiant remains visible most of the night, but rates tend to be low. However, the shower produces occasional fireballs, so it doesn’t hurt to keep an eye on it.

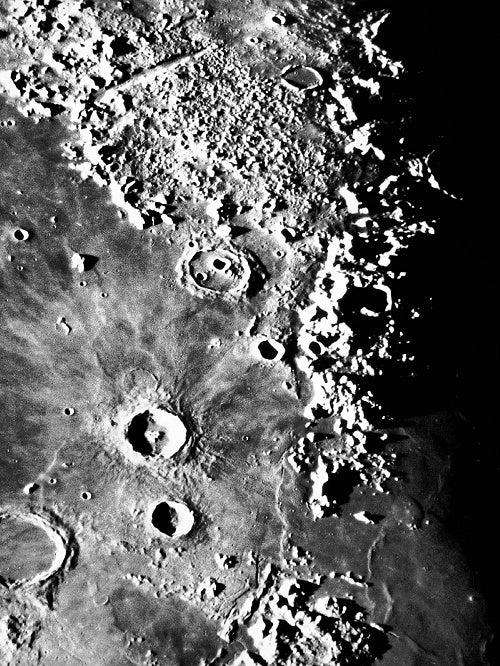

With a spacecraft carrying the name of the famed Italian-born French astronomer Giovanni Cassini, it seems appropriate to highlight a lunar feature bearing the same name. (Although the crater takes its name from both Giovanni and his son, Jacques.) First recorded on a lunar map dating to 1692, Cassini stands as one of the more unusual craters on the Moon. The 35-mile-wide crater lies northeast of Archimedes and southeast of Plato in the easternmost region of Mare Imbrium close to the lunar Alps.

Two large craters — called Cassini A (10.5 miles across) and Cassini B (5.5 miles across) — dominate the main crater’s floor. Under low lighting conditions, you also may spot the tiny crater that lies just inside the northern wall. A fresh crater resembling Cassini B lies on the outer ramparts northwest of the main crater. Lava fills the main crater’s floor almost to the top of the wall, especially at the southern end. A pair of short rilles occupies the space between Cassini A and the eastern wall of the main crater. These are best seen a few days after the Sun rises over the crater, an event that occurs when the Moon is 8 days old. This month, that comes November 19.

After plunging behind the Sun in October, Comet C/2003 K4 (LINEAR) reappears in the morning sky. It should glow around 5th magnitude, putting it well within range of binoculars from a city backyard. Throughout November, the comet remains low in the gathering dawn as it continues to journey south, becoming well-placed for observers south of the equator.

C/2003 K4 will appear best if you have a clear horizon to the southeast. The comet starts off in the middle of Corvus the Crow, well below Leo and to the lower right of Venus and Jupiter. If you’re out watching the planetary conjunction on the 5th, take a few minutes to observe the comet. The Last Quarter Moon won’t interfere much. A look through a telescope reveals the comet’s condensed central region and stubby tail, which lies nearly parallel to the horizon.

If you can’t wait until morning, or don’t like to get up early, three comets come within reach of 10-inch scopes after dusk. C/2001 Q4 (NEAT), that nice spring comet, slices through Draco’s neck not far from the Cat’s Eye Nebula (NGC 6543). At 12th magnitude, Q4 is not for the faint of heart. Almost as hard to find is 12th-magnitude C/2003 T4 (LINEAR). It also lies in Draco, floating across the primary star-hopping route to the Splinter Galaxy (NGC 5907). Periodic comet 78P/Gehrels 2 arcs to the southwest of the Pleiades star cluster.

Regular readers won’t be surprised to find that asteroids

4 Vesta and 9 Metis continue to arc together through southern Aquarius. At magnitude 7.4, Vesta is pretty easy to follow through binoculars. It lies about one field of view below the wide triplet Psi1 (ψ1), Psi2 (ψ2), and Psi3 (ψ3) Aquarii. Metis proves a lot tougher because it glows at magnitude 10.2, significantly fainter than the planet Neptune.

Hide in plain sight

Despite the number of aircraft in the sky, it’s not that common for their shadow to sweep across you — you have to be in the right place at the right time. Asteroids suffer the same fate. With a little bit of planning and a decent dose of luck, however, you can stand in the shadow of a space rock as it briefly blocks the light from a distant star.

IOTA makes predictions for and analyzes data from asteroid occultations. Their web site contains shadow paths and times for events around the world. Any one place typically has a couple good chances a year. A cool event runs along a thin band from Texas to Maine around 9:30 p.m. EST November 5, when an 18th-magnitude asteroid hides 4.7-magnitude Lambda (λ) Aquarii. Just after 11 p.m. EST on the 28th, asteroid 1698 Christophe blots out 6th-magnitude 81 Aquarii for observers in the Gulf States.