Friday, September 15

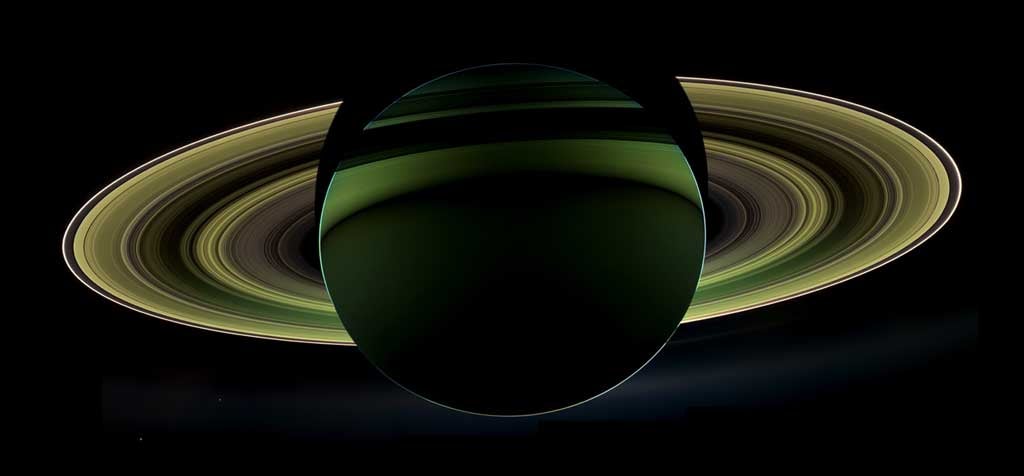

Although Saturn reached opposition three months ago today, it remains a tempting target in the evening sky. The ringed world stands some 25° high in the south-southwest as twilight fades to darkness and doesn’t dip below the horizon until close to midnight local daylight time. Saturn shines at magnitude 0.5 against the backdrop of southern Ophiuchus, a constellation whose brightest star glows six times fainter than the planet. When viewed through a telescope, Saturn’s globe measures 17″ across while its spectacular ring system spans 38″ and tilts 27° to our line of sight. As you gaze upon Saturn from afar this evening, it’s the first time in more than 13 years that the Cassini spacecraft is not observing the ringed planet from up close. The robotic probe burned up in the gas giant’s atmosphere earlier today.

Saturday, September 16

Mercury and Mars have appeared near each other in the predawn twilight for the past week, but they make their closest approach this morning. For North American observers, they slide just 0.25° (half the Full Moon’s diameter) apart and lie in the same low-power field through a telescope. (Mercury spans 6.4″ and is about two-thirds lit; Mars is 3.6″ across and full.) Both lie 10° high in the east a half-hour before sunrise, with Mercury shining some 10 times brighter than its neighbor.

Sunday, September 17

The waning crescent Moon points toward three planets and a star this morning. The slim crescent stands 6° above magnitude –3.9 Venus with Leo the Lion’s luminary, magnitude 1.4 Regulus, 3° below the planet. Mars and Mercury huddle 11° below Venus.

This evening provides a nice opportunity to see Saturn’s seven brightest moons through a telescope. The toughest to spot normally are the two inner ones — Mimas and Enceladus — which never stray far from the rings’ glare. But tonight, the two satellites reach greatest western elongation within two hours of each other. Tethys, Dione, Rhea, and Titan show up more clearly because they glow brighter and lie farther from the planet. Distant Iapetus rounds out Saturn’s “magnificent seven” satellites on display. If you draw a line from Saturn to 8th-magnitude Titan and extend it an equal distance, 11th-magnitude Iapetus will be right there.

Monday, September 18

The predawn fireworks appear even more spectacular this morning. A wafer-thin crescent Moon hangs below Venus and above the Mercury-Mars pair. The latter two worlds are now separated by 1.5°.

Tuesday, September 19

Uranus reaches opposition one month from today, but it already has become a tempting evening target. The ice giant world rises before 9 p.m. local daylight time and climbs some 30° above the eastern horizon by 11 p.m. The magnitude 5.7 planet lies in Pisces, 1.1° northwest of magnitude 4.3 Omicron (o) Piscium. Although Uranus glows brightly enough to see with the naked eye under a dark sky, binoculars make the task much easier. A telescope reveals the planet’s blue-green disk, which spans 3.7″.

Wednesday, September 20

New Moon occurs at 1:30 a.m. EDT. At its new phase, the Moon crosses the sky with the Sun and so remains hidden in our star’s glare.

Thursday, September 21

Although you can’t see the Moon around its New phase, its absence from the morning sky these next two weeks provides observers with an excellent opportunity to view the zodiacal light. From the Northern Hemisphere, early autumn is the best time for viewing this elusive glow before sunrise. It appears slightly fainter than the Milky Way, so you’ll need a clear moonless sky and an observing site located far from the city. Look for a cone-shaped glow that points nearly straight up from the eastern horizon shortly before morning twilight begins (around 5 a.m. local daylight time at mid-northern latitudes). The Moon remains out of the morning sky until October 4, when the waxing gibbous world returns and overwhelms the much fainter zodiacal light.

Friday, September 22

With the days growing shorter and kids back in school, it shouldn’t be surprising that summer’s reign is just about over. The warmest season comes to an official close at 4:02 p.m. EDT, when Earth reaches the autumnal equinox. This marks the moment when the Sun crosses the celestial equator traveling south. Our star rises due east and sets due west today. If the Sun were a point of light and Earth had no atmosphere, everyone would get 12 hours of sunlight and 12 hours of darkness. But the air and finite size of our star make today a few minutes longer than 12 hours.

The Moon appears as a waxing crescent low in the west-southwest during evening twilight. Tonight, you can use it as a guide for finding Jupiter. Although the gas giant planet has been a conspicuous evening object for the past several months, it’s now nearing the end of its reign. The giant planet lies 8° to the lower right of the Moon but just 6° above the horizon a half-hour after sundown. Still, at magnitude –1.7, Jupiter shines brightly enough to appear prominent against the twilight glow.

Saturday, September 23

The variable star Algol in Perseus reaches minimum brightness at 2:56 a.m. EDT. Observers on the East Coast who start watching around midevening on the 22nd can see the star’s brightness diminish by 70 percent over the course of about five hours. Those in western North America will see Algol brighten noticeably from late evening until dawn starts to paint the sky, when the star passes nearly overhead. This eclipsing binary system runs through a cycle from minimum (magnitude 3.4) to maximum (magnitude 2.1) and back every 2.87 days.

Sunday, September 24

Although autumn arrived with the equinox two days ago, the Summer Triangle remains prominent in the evening sky. Look high in the west after darkness falls and your eyes will fall on the brilliant star Vega in the constellation Lyra the Harp. At magnitude 0.0, Vega is the brightest member of the Triangle. The second-brightest star, magnitude 0.8 Altair in Aquila the Eagle, lies some 35° southeast of Vega. The asterism’s dimmest member, magnitude 1.3 Deneb in Cygnus the Swan, stands about 25° east-northeast of Vega. For observers at mid-northern latitudes, Deneb passes through the zenith around 9:30 p.m. local daylight time, more than an hour after the last vestiges of twilight disappear.