Friday, November 8

Although the constellation Perseus is perhaps best known for housing the famous Double Cluster, it’s also home to another open star cluster: M34, one of the Hero’s two Messier objects.

M34 is some 180 million years old and sits 1,400 light-years from Earth. The cluster contains about 100 stars and takes up roughly the same area on the sky as the Full Moon. On a clear, dark night, it’s visible to the naked eye and is easy to center in binoculars or any telescope for further enjoyment. In fact, you’ll want to use low magnification, as this will show more of its scattered stars. Bumping the magnification up a bit higher will show fainter members, though it will also limit your field of view, so try switching between low and medium powers to see it all.

You can find 5th-magnitude M34 just 5.2° northwest of Perseus’ famous beta star, Algol, also called the Demon Star.

Sunrise: 6:38 A.M.

Sunset: 4:49 P.M.

Moonrise: 1:04 P.M.

Moonset: 10:56 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (44%)

*Times for sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset are given in local time from 40° N 90° W. The Moon’s illumination is given at 12 P.M. local time from the same location.

Saturday, November 9

First Quarter Moon occurs early this morning at 12:55 A.M. EST.

Mercury passes 2° north of the bright star Antares in Scorpius at 11 P.M. EST. You can catch the two in the early-evening sky if you’re quick — some 30 minutes after sunset, the pair is only 3° above the southwestern horizon, with Antares just starting to pop out against the slowly darkening sky. Antares glows at magnitude 1.1, so you will certainly spot magnitude –0.3 Mercury more easily, just to Antares’ upper right. So, try centering the planet in binoculars or a small scope, then scanning slowly just a little to the lower left to look for the star. An aging red giant, Antares’ light is distinctly crimson.

Mercury currently stands nearly 106 million miles (170.5 million kilometers) from Earth. Its disk appears 6” wide and shows off a gibbous phase at 76 percent lit. Compare this with Venus, which stands to Mercury’s far upper left, higher in the sky (some 14° above the horizon) half an hour after sunset and some 30 times brighter at magnitude –4. Venus, just a tad closer to Earth at 104 million miles (168 million km), is also physically larger than Mercury. It appears 15” in diameter and shows off roughly the same phase in a telescope, 75 percent lit.

Sunrise: 6:39 A.M.

Sunset: 4:48 P.M.

Moonrise: 1:34 P.M.

Moonset: —

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (56%)

Sunday, November 10

The Moon, now in Aquarius, passes just 0.09° north of Saturn at 9 P.M. EST. Look for the pair in the southern sky soon after sunset; our satellite is now some 70 percent lit, but you should still be able spot Saturn’s magnitude 0.8 glow nearby. The planet outshines the stars in this region of the sky, and binoculars or a telescope will show off its 18”-wide disk.

The rings, now tilted some 5° to our line of sight, stretch 41” from end to end. You may even be able to identify the planet’s largest and brightest moon, 8th-magnitude Titan, some 2’ to Saturn’s west — though don’t be surprised if our own bright, nearby Moon makes this difficult. Several smaller, 10th-magnitude moons cluster closer to the planet, but these will likely be washed out by the moonlight.

Even if you aren’t able to get out early in the evening, the pair is visible until well after local midnight, standing highest in the south around 7 P.M. local time and setting in the west around 1:30 A.M. local time.

Sunrise: 6:40 A.M.

Sunset: 4:47 P.M.

Moonrise: 2:01 P.M.

Moonset: 12:09 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (67%)

Monday, November 11

The Moon now passes 0.6° north of Neptune at 9 P.M. EST. Our satellite has moved into Pisces and hangs just beneath the Circlet asterism an hour after sunset. Neptune is not visible to the naked eye even under a dark sky, and the nearby bright Moon will make finding it in binoculars or a telescope even more challenging. Nonetheless, scan the region near the Moon with your optics for the distant ice giant’s magnitude 7.7, 2”-wide disk. Compared with the background stars, it will look like a “flat,” bluish-gray star. You may have better luck overnight and into the early-morning hours, say around about 1 A.M. local time. By then, the Moon will have moved on a bit, and the added distance between our satellite and the faint planet may aid your search.

Early-evening observers up for a different sort of challenge can focus in on Venus soon after sunset. Tonight, the bright planet sits just 1.5° south of the Lagoon Nebula (M8) in Sagittarius. Although you may have trouble spotting the nebula itself, as the region is setting as darkness falls and the bright gibbous Moon is throwing light across the sky, you should definitely be able to spot the open star cluster embedded within the emission nebula with either binoculars or a telescope. That cluster, cataloged as NGC 6530, is a magnitude 4.6 object situated in the Lagoon’s slightly wispier eastern half. Try searching out the nebula with as large a telescope as you can — larger scopes should be able to capture enough of its light, even in the bright, moonlit sky, to show a bit of the glow from this cosmic gas and dust. And remember this location for later — on a clear, moonless night, even a small, 4-inch scope will show detail within the Lagoon, such as the dark dust lane separating its two halves.

Sunrise: 6:41 A.M.

Sunset: 4:46 P.M.

Moonrise: 2:25 P.M.

Moonset: 1:23 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (77%)

Tuesday, November 12

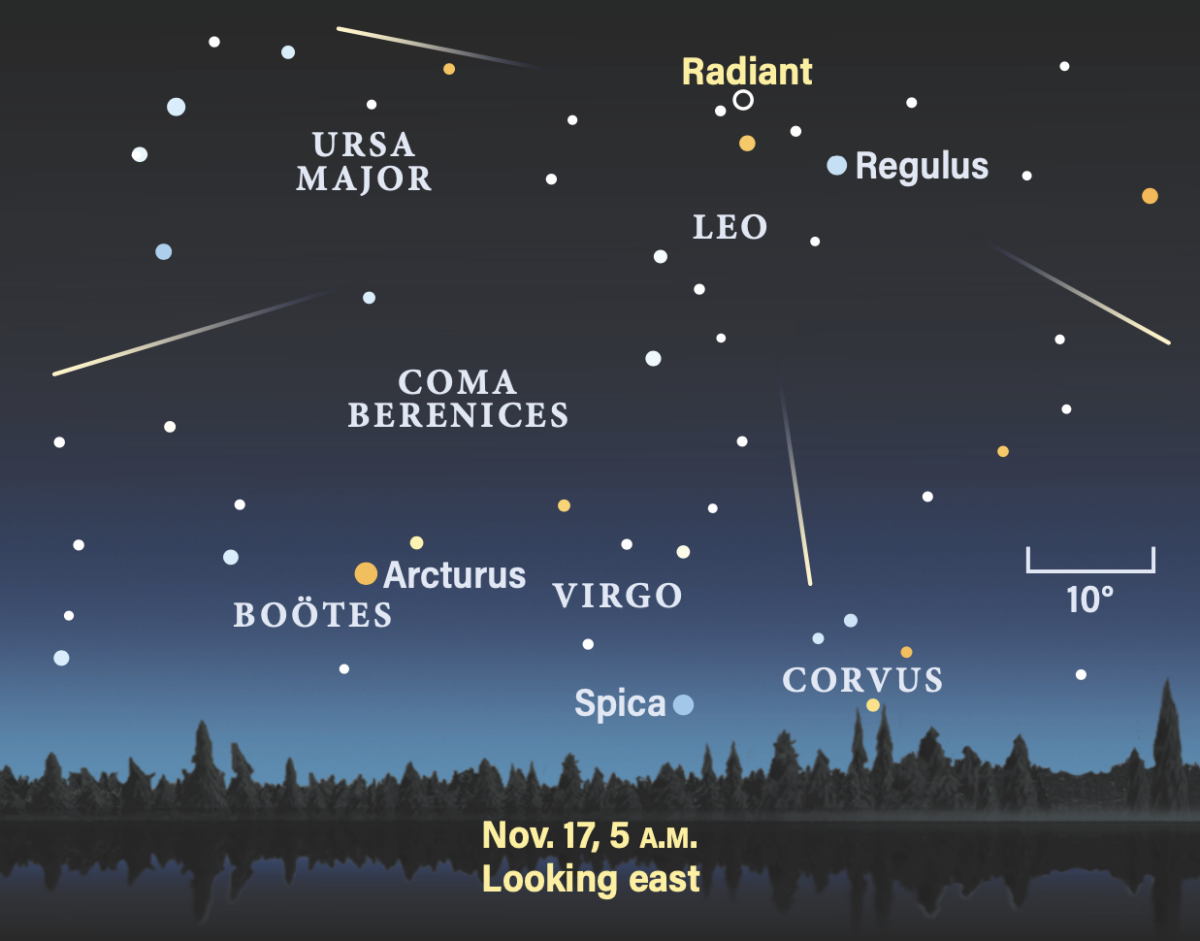

Although the Leonids meteor shower won’t peak until next week, now is the time to try to spot shower meteors streaking across the sky. With the Moon setting around 2:30 A.M. local time, the few hours before sunrise are ideal for tracking down Leo the Lion, within which the shower’s radiant sits. The radiant, located just west of 3rd-magnitude Zeta (ζ) Leonis, is the point on the sky from which the Leonids appear to radiate. So, once you’ve found the Lion high in the eastern sky, scan some 40° to 60° to the great cat’s left or right for shooting stars. These regions of the sky are where meteors will leave the longest trails.

Even at their peak, the Leonids are only expected to produce about 10 meteors per hour. So, while you won’t see innumerable shooting stars streaking across the sky, you can expect to enjoy several meteors light up overhead in a given hour.

Sunrise: 6:42 A.M.

Sunset: 4:46 P.M.

Moonrise: 2:50 P.M.

Moonset: 2:37 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (86%)

Wednesday, November 13

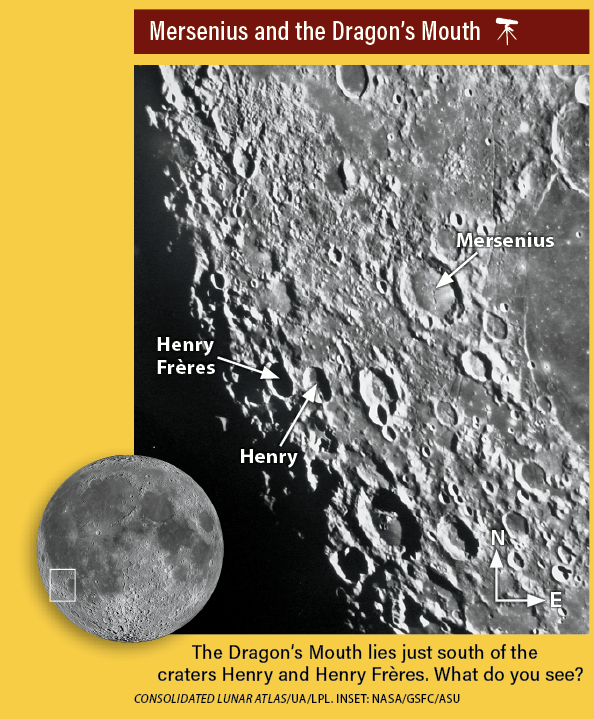

The bright waxing gibbous Moon is already well above the eastern horizon as darkness falls after sunset this evening. Now it’s time to focus in on our satellite — pull out your telescope and home in on the southwestern portion of the disk, near the limb. This is where the Dragon’s Mouth lies — a play of shadows and light across the terrain here that only appears briefly and under the right Sun angle.

Look first for the crater Mersenius just west of Mare Humorum, the Sea of Moisture. Mersenius has a low, worn-away rim and a floor pocked with craterlets and crossed by cracks (called rilles). To Mersenius’ southwest are the smaller craters Henry and Henry Frères — it is south of these features that the Dragon’s Mouth appears, looking like “a mouthful of very bright teeth,” according to lunar observer David Gamble. These teeth are actually illuminated lunar mountains, but perhaps your mind’s eye can turn them into the same — or a different — fanciful sight.

Sunrise: 6:43 A.M.

Sunset: 4:45 P.M.

Moonrise: 3:16 P.M.

Moonset: 3:54 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (93%)

Thursday, November 14

The Moon reaches perigee, the closest point to Earth in its orbit, at 6:16 A.M. EST. At that time, our satellite will sit just 223,762 miles (360,110 kilometers) away. This cosmic setup comes just in time for tomorrow’s Full Moon, which will be a Super Moon (a phenomenon that occurs when the Moon is Full at the same time it is nearest our planet). It will be the last Super Moon in 2024.

That bright Moon is also why we’re focused on the early-morning hours today. In the 90 minutes before sunrise, the sky is moonless and full of stars. The Big Dipper hangs upside-down in the north, pouring into the smaller Little Dipper, at the end of whose handle is one of the most famous stars in the sky: Polaris, the North Star. This 2nd-magnitude sun is not particularly bright but still visible to the naked eye, gaining notoriety by being the star currently located above the North Celestial Pole.

To the Little Dipper’s right is the W-shaped form of the constellation Cassiopeia the Queen, meant to depict the ruler on her throne. She sits upright for half the night, but upside-down for the other half as punishment from the gods. To Cassiopeia’s lower right is the house-shaped constellation Cepheus the King, Cassiopeia’s husband. Her daughter, Andromeda, has a constellation as well, though for most locations this star pattern is largely below the horizon at this time. Instead, Andromeda is visible arcing over the North Celestial Pole in the evening at this time of year.

Sunrise: 6:45 A.M.

Sunset: 4:44 P.M.

Moonrise: 3:46 P.M.

Moonset: 5:12 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (98%)

Friday, November 15

Full Moon occurs at 4:29 P.M. EST. The November Full Moon is also called the Beaver Moon, and this one is also a Super Moon. It’s the fourth in a series of four back-to-back Super Moons, all occurring when the Moon is Full while near perigee, the closest point to Earth in its elliptical orbit around our planet. At the moment the Moon reaches Full, it will be 224,853 miles (361,866 km) from Earth, making it the third brightest of the four Super Moons this year (last month’s Super Moon was the biggest and brightest of the batch).

In addition to shining big and bright in our sky, the Moon has even more going on tonight. Our satellite passes 4° north of Uranus at 8 P.M. EST; at that time, the Moon stands just to the right of the Pleiades (M45), a bright open star cluster in Taurus the Bull. South of the Moon, the solar system’s penultimate planet shines at magnitude 5.6 and will require binoculars or a telescope to spot. Uranus’ tiny disk appears nearly 4” across — look for its grayish hue.

And keep watching The Moon. Our satellite continues tracking toward the Pleiades and, within a few hours (starting late on the 15th in the western U.S. and early on the 16th farther east), the Moon occults several stars in the cluster, passing in front of them and hiding them from view behind its bright face. We’ll cover this exciting event in our column next week, so stay tuned!

Sunrise: 6:46 A.M.

Sunset: 4:43 P.M.

Moonrise: 4:21 P.M.

Moonset: 6:32 A.M.

Moon Phase: Full

Sky This Week is brought to you in part by Celestron.