The variable star Algol in Perseus reaches minimum brightness at 2:57 a.m. EST tomorrow morning. If you start watching it early this evening, you can see its brightness diminish by 70 percent over the course of about five hours as its magnitude drops from 2.1 to 3.4. This eclipsing binary star runs through a cycle from minimum to maximum and back every 2.87 days. Algol appears nearly overhead around midnight local time and remains well above the northwestern horizon until dawn.

Saturday, November 9

Brilliant Venus stands out low in the southwest during evening twilight. The planet lies 6° above the horizon a half-hour after sunset and sets around 6 p.m. local time. Magnitude –3.8 Venus is the brightest object in the evening sky with the obvious exception of the Moon. Although the inner world crossed from Scorpius into Ophiuchus yesterday, this evening it appears 4° due north (upper right) of the Scorpion’s brightest star, 1st-magnitude Antares. Binoculars can help you spot the star’s ruddy glow against the twilight background.

Sunday, November 10

A lone bright star now hangs low in the south during early evening. First-magnitude Fomalhaut — often called “the Solitary One” — belongs to the constellation Piscis Austrinus the Southern Fish. From mid-northern latitudes, it climbs 20° above the horizon at its best. How solitary is Fomalhaut? The nearest 1st-magnitude star to it, Achernar at the southern end of Eridanus the River, lies some 40° away.

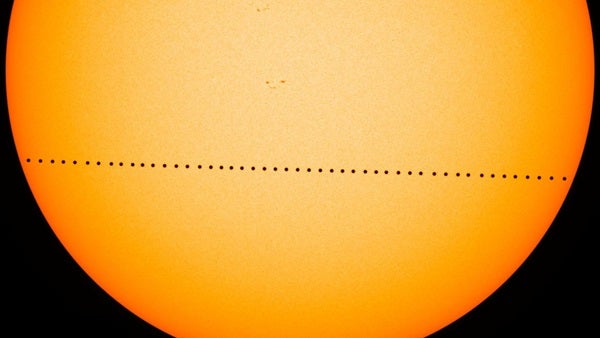

Mercury passes directly between the Sun and Earth today for the first time since May 9, 2016. The innermost planet’s dark disk will cross the Sun’s face for 5.5 hours. Observers across most of North and South America, Europe, and Africa can view at least some of this transit. This is a morning event for most North Americans. Mercury first touches the solar disk at 7:35 a.m. EST, lies closest to the Sun’s center at 10:20 a.m., and leaves our star’s limb at 1:04 p.m. You’ll need a telescope equipped with a safe, full-aperture solar filter to see this event. For complete viewing details, see “Observe the transit of Mercury” in the November issue of Astronomy. If you miss this event, you’ll have to wait until November 2032 to see another; the next one visible from North America won’t occur until May 2049.

Full Moon officially arrives at 8:34 a.m. EST tomorrow morning, but it will look completely illuminated both tonight and tomorrow night. You can find it rising in the eastern sky around sunset and then watch it climb highest in the south by midnight local time. It dips low in the west by the time morning twilight starts to paint the sky. The Moon lies against the backdrop of southern Aries tonight. By tomorrow evening, it will appear among the background stars of Taurus the Bull, west of the Hyades star cluster and south of the Pleiades.

Tuesday, November 12

This morning provides a nice opportunity to spot Mars near the beginning of its 20-month-long apparition. If you look low in the east-southeast about an hour before the Sun rises, the first object you’ll see is 1st-magnitude Spica, Virgo the Maiden’s brightest star. Look more closely and you should notice Mars’ ruddy glow just 3° to its left. Shining at magnitude 1.8, the planet appears half as bright as the star. Mars will grow more conspicuous over the coming months as it approaches a spectacular opposition in October 2020.

Wednesday, November 13

Saturn remains a glorious sight this week. The ringed planet resides among the background stars of Sagittarius the Archer, a region that appears 20° high in the southwest as twilight fades to darkness and doesn’t set until after 8 p.m. local time. Saturn shines at magnitude 0.6 and appears significantly brighter than any of its host constellation’s stars. Although a naked-eye view of the planet is nice, seeing it through a telescope truly inspires. Even a small instrument shows the distant world’s 16″-diameter disk and spectacular ring system, which spans 36″ and tilts 25° to our line of sight.

Thursday, November 14

As Venus inches higher with each passing day, it appears to be on a collision course with Jupiter. Although Jupiter shines two magnitudes fainter than Venus, the magnitude –1.9 gas giant world is still the night sky’s second-brightest point of light. This evening, the two planets stand 10° apart — about the span of your closed fist when held at arm’s length. The gap will narrow by 1° per day, setting up a dramatic conjunction late next week. If you point a telescope at Jupiter this week, you’ll see a 33″-diameter disk with striking details in its dynamic atmosphere.

Friday, November 15

Look high in the southeast after darkness falls this week, and you should see autumn’s most conspicuous star group. The Great Square of Pegasus stands out in the evening sky at this time of year, though it appears balanced on one corner and looks more diamond-shaped. These four almost equally bright stars form the body of Pegasus the Winged Horse. The fainter stars that represent the rest of this constellation’s shape trail off to the square’s west.

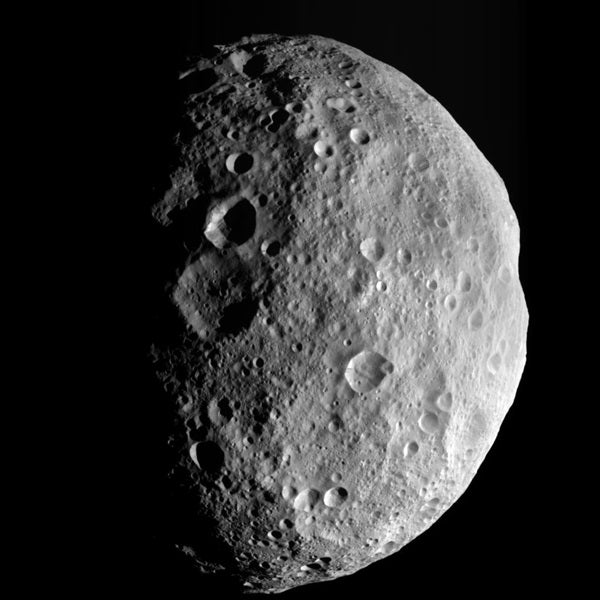

Although asteroid 4 Vesta reached opposition and peak visibility the night of November 11/12, the Full Moon was only a few degrees away that night and made finding the magnitude 6.5 space rock a serious challenge. Now that the Moon has moved well away — and Vesta shines just as brightly as it did at opposition — locating the asteroid through binoculars should prove much easier. The brightest asteroid lies in northeastern Cetus tonight, 3° west of the 4th-magnitude star Omicron (ο) Tauri and 5° northeast of 3rd-magnitude Alpha (α) Ceti.

Sunday, November 17

The Leonid meteor shower reaches its peak before dawn tomorrow morning. Although typically one of the year’s finer meteor showers, this year’s Leonid display suffers because it comes just a few days after Full Moon. A 65-percent-lit waning gibbous Moon shares the sky with the shower, drowning out the fainter “shooting stars” and rendering the bright ones less impressive. Still, the Leonids produce more fireballs than most meteor showers, so it should still be worth keeping an eye on the predawn sky.