After a three-month hiatus lost in the Sun’s glare, Venus returns to view after sunset in mid-October. It’s not easy to see, however — this evening, the inner planet stands just 2° high in the west-southwest a half-hour after sundown. Luckily, it shines brilliantly at magnitude –3.8 and should show up if you have a haze-free sky and unobstructed horizon. Despite this pedestrian start to its evening apparition, Venus will be a glorious sight this coming winter and spring.

Saturday, October 19

Mercury reaches greatest elongation at midnight EDT. At that time, the innermost planet stands 25° east of the Sun. To observers north of the equator, however, Mercury climbs just 3° high 30 minutes after sunset. The easiest way to spot it is to first find Venus gleaming low in the west-southwest. This evening, Mercury lies 7° to its neighbor’s left. If you place Venus at the right edge of the field through your binoculars, you should see Mercury’s magnitude –0.1 glow near the field’s left edge.

Sunday, October 20

The night sky’s most conspicuous harbinger of winter now rises in the east around 11 p.m. local daylight time. The constellation Orion the Hunter appears on its side as it rises, with ruddy Betelgeuse to the left of the three-star belt and blue-white Rigel to the belt’s right. As Orion climbs higher before dawn, the figure rotates so that Betelgeuse lies at the upper left and Rigel at the lower right of the constellation pattern.

Monday, October 21

Last Quarter Moon occurs at 8:39 a.m. EDT. It rose around 11:30 p.m. local daylight time yesterday evening, which gives North American observers a chance to see it almost precisely half-lit before this morning’s dawn. Earth’s only natural satellite appears among the background stars of eastern Gemini.

Although the Orionid meteor shower peaks this morning, a fat crescent Moon shares the sky and will drown out some of the fainter “shooting stars.” The Orionids typically produce up to 20 meteors per hour, but the Moon’s presence likely will cut that number in half. Your best bet is to find an observing site where you can place the Moon behind a building or trees. Orionid meteors appear to radiate from the northern part of the constellation Orion the Hunter.

The variable star Algol in Perseus reaches minimum brightness around 11:04 p.m. EDT, when it shines at magnitude 3.4. If you start tracking it this evening, you can watch it more than triple in brightness (to magnitude 2.1) by dawn. This eclipsing binary star runs through a cycle from minimum to maximum and back every 2.87 days. Algol remains visible all night, passing nearly overhead around 2 a.m. local daylight time.

Wednesday, October 23

Jupiter continues to dominate the early evening sky from its perch in southern Ophiuchus the Serpent-bearer. The giant planet shines at magnitude –1.9 and stands 15° above the southwestern horizon an hour after sunset. When viewed through a telescope, Jupiter shows a 34″-diameter disk with striking details in its dynamic atmosphere. You also should see four bright points of light arrayed around the planet: the Galilean moons Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

Thursday, October 24

Neptune appeared at its best at opposition in September, but its visibility hardly suffers in October. The outermost major planet lies some 35° above the southeastern horizon once darkness falls and climbs highest in the south around 10 p.m. local daylight time. Neptune glows at magnitude 7.8, which is bright enough to spot through binoculars if you know where to look. The trick is to find the 4th-magnitude star Phi (φ) Aquarii, which lies about 15° (two binocular fields) east-southeast of Aquarius’ distinctive Water Jar asterism. Tonight, Neptune appears 1.2° west-southwest of Phi. When viewed through a telescope, the ice giant planet shows a blue-gray disk measuring 2.3″ across. To learn more about viewing Neptune and its outer solar system cousin, Uranus (which reaches opposition at the end of this week), see “Observe the ice giants” in October’s Astronomy.

Friday, October 25

Look high in the southeast after darkness falls this week, and you should see autumn’s most conspicuous star group. The Great Square of Pegasus stands out in the evening sky at this time of year, though it appears balanced on one corner and looks more diamond-shaped. These four almost equally bright stars form the body of Pegasus the Winged Horse. The fainter stars that form the rest of this constellation’s shape trail off to the square’s west.

Saturday, October 26

Saturn remains a glorious sight this week. The ringed planet resides among the background stars of Sagittarius the Archer, a region that appears 25° high in the south-southwest as twilight fades to darkness and doesn’t set until close to 10:30 p.m. local daylight time. Saturn shines at magnitude 0.5 and appears significantly brighter than any of its host constellation’s stars. Although a naked-eye view of the planet is nice, seeing it through a telescope truly inspires. Even a small instrument shows the distant world’s 16″-diameter disk and spectacular ring system, which spans 37″ and tilts 25° to our line of sight.

The Moon reaches perigee, the closest point in its orbit around Earth, at 6:39 a.m. EDT. It then lies 224,508 miles (361,311 kilometers) away from us.

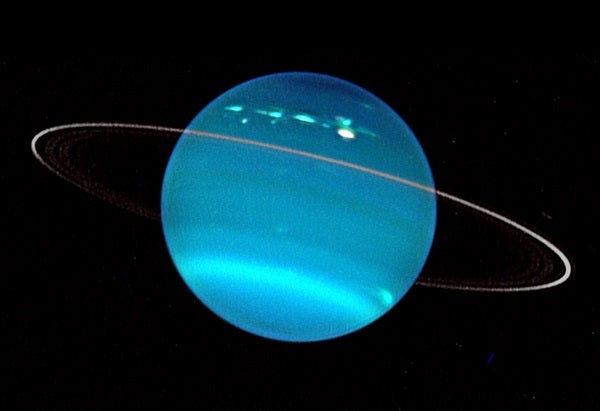

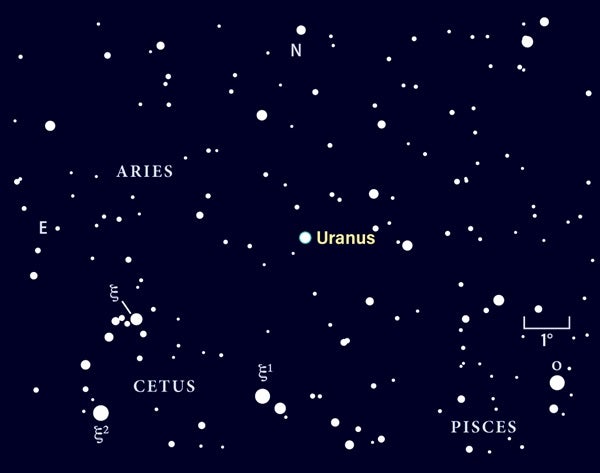

Uranus reaches opposition and peak visibility tonight. Opposition officially arrives at 4 a.m. EDT on the 28th, when the outer planet lies opposite the Sun in our sky. This means it rises at sunset, climbs highest in the south around 1 a.m. local daylight time, and sets at sunrise. (From 40° north latitude, Uranus peaks at an altitude of 63°, the highest it has appeared at opposition since February 1962.) The magnitude 5.7 planet lies among the background stars of southern Aries. In the nights around opposition, you can find it 3° south-southwest of the similarly bright star 19 Arietis.. Although Uranus shines brightly enough to glimpse with the naked eye under a dark sky, use binoculars to locate it initially. A telescope reveals the planet’s blue-green disk, which spans 3.7″.

New Moon occurs at 11:38 p.m. EDT. At its New phase, the Moon crosses the sky with the Sun and so remains hidden in our star’s glare.