Friday, October 4

Now that autumn is officially upon the Northern Hemisphere, the familiar wintertime constellations are rising earlier each night. One of those constellations is Taurus, now some 30° above the eastern horizon by local midnight.

The brightest star in Taurus is the Bull’s red giant eye, Aldebaran. (Don’t mistake brighter Jupiter, now in eastern Taurus near the tips of the Bull’s horns, for the star!) Just above Aldebaran as the constellation is rising this evening is NGC 1554/55, an emission nebula near the famous variable star T Tauri. Well — you’ll find NGC 1555, also called Hind’s Variable Nebula. NGC 1554, often called Struve’s Lost Nebula, is — as the name may imply — no longer visible. But NGC 1555 can be found within 1’ of T Tau, especially on a dark, moonless night like tonight.

To find mid-9th-magnitude T Tau, first skip 3.2° northwest of Aldebaran to land on magnitude 3.5 Epsilon (ε) Tau. From this star, move 1.6° due west to locate T Tau; the nebula is just west of the star. Hind’s Variable Nebula is, as its name implies, variable. Its brightness and even extent vary with the output of the nearby star, and you’ll want the largest telescope you have access to when you try to view it. A nebula filter can help, as will taking long-exposure photographs to help gather more photons from the elusive cosmic cloud.

Sunrise: 7:00 A.M.

Sunset: 6:36 P.M.

Moonrise: 8:47 A.M.

Moonset: 7:19 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (3%)

*Times for sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset are given in local time from 40° N 90° W. The Moon’s illumination is given at 12 P.M. local time from the same location.

Saturday, October 5

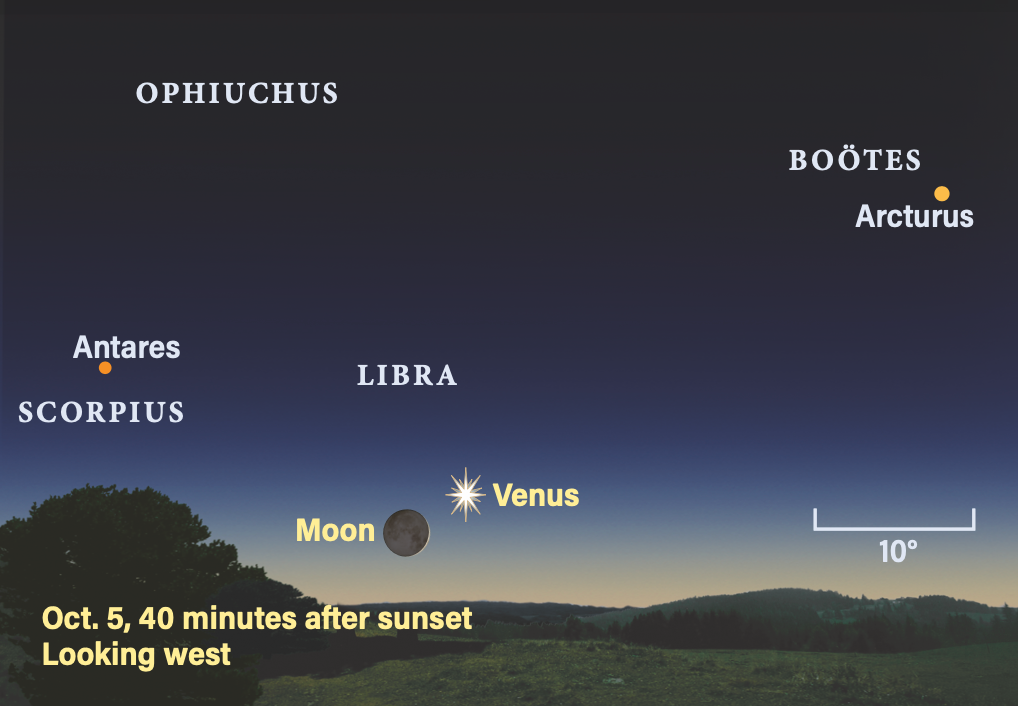

The Moon passes 3° south of Venus at 4 P.M. EDT; if you step outside this evening shortly after sunset, you can still catch the two close together in the soft glow of twilight before they set.

Venus is is a bright, blazing evening star sinking in the southwest. Half an hour after the Sun disappears, it is just under 10° high, with a delicate crescent Moon less than 5° to its lower left.

Bright twilight is an excellent time to observe Venus through a telescope, as the lighter background of the sky lets you better see the bright planet’s phase. Venus’ disk now stretches 13” across and is 84 percent lit. Compare that to our Moon, which is just 9 percent lit by this evening, with much of its face still in darkness. However, that darkness might not be complete — you may be able to make out several lunar features thanks to earthshine, caused by sunlight bouncing off Earth to illuminate the Moon, even when portions of it are in Earth’s shadow.

Although readily visible to the naked eye, earthshine can create a striking view particularly when viewing our satellite through binoculars or a telescope at low power. Try using your finder scope, which will likely show the entire Moon, rather than only a small portion of its surface.

Sunrise: 7:01 A.M.

Sunset: 6:35 P.M.

Moonrise: 9:49 A.M.

Moonset: 7:45 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (8%)

Sunday, October 6

Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) is continuing to delight, now approaching Earth after rounding the Sun in late September. Recently recorded at 2nd magnitude (though things can change quickly!), it’s still visible shortly before sunrise for those with a clear eastern horizon.

About half an hour before sunrise, the comet is just under 3° high in the east and slowly rising. Although it’s bright, your best bet for spotting it will be with binoculars or a small telescope. Its azimuth, or offset from due north, is 98°, or just 8° south of due east. You may be able to still spot 1st-magnitude Regulus high up in the eastern sky; if so, drop down and just slightly left from this star for the comet’s position, again very low to the horizon.

Visually, observers report a tail roughly a degree in length. Astrophotographers, however, have been able to tease out a tail some four times that long. It could be an excellent morning to try for some landscape photography, using long exposures to pull the comet out of the bright twilight with your camera.

Related: Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS stuns in photos at perihelion

Sunrise: 7:02 A.M.

Sunset: 6:33 P.M.

Moonrise: 10:53 A.M.

Moonset: 8:15 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (13%)

Monday, October 7

Asteroid 39 Laetitia reaches opposition at 2 P.M. EDT; we’ll check in with this main-belt world tomorrow in the evening sky.

The Moon passes 0.2° south of the bright star Antares in Scorpius at 3 P.M. EDT. An hour after sunset, the two appear side by side in the southwestern sky, with the body and long, curving tail of the Scorpion low to the horizon for most mid-latitude observers.

The Moon is now some 23 percent lit and stands just above magnitude 2.8 Tau (τ) Scorpii. To its right is 1st-magnitude Antares, whose glow may appear reddish in the falling darkness. Like Aldebaran in Taurus, which we observed earlier this week, Antares is an aging red giant star. Its color is such that it’s often confused for Mars in the sky.

Brilliant Venus, low to the horizon by this time, is now far to the pair’s lower right, showing just how wide a swath of the sky the Moon has traveled in just a few days. To the upper left of Scorpius is the Teapot asterism in the constellation Sagittarius; just above the Teapot’s spout is the direction of the center of our Milky Way Galaxy and the place where its supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A*, resides.

Sunrise: 7:03 A.M.

Sunset: 6:32 P.M.

Moonrise: 11:57 A.M.

Moonset: 8:53 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (21%)

Tuesday, October 8

Let’s return to Laetitia, now one day past opposition and visible in the sky most of the night. Located in the constellation Cetus, Laetitia is rising at sunset and highest in the sky around 1 A.M. local daylight time.

Late this evening, you’ll find Laetitia climbing in the south, some 5.3° north-northwest of the magnitude 3.6 star Theta (θ) Ceti. Glowing at magnitude 9.5, the asteroid will require binoculars or a telescope, and its motion is slow enough that you won’t see it move during a single observing session. However, if you locate the region where Laetitia sits and make a sketch or take a photograph, returning each night for the next few nights and doing the same will reveal one dot that’s moving — that’s Laetitia.

Some 15° south-southwest of this region is magnitude 2 Diphda (Beta [β] Ceti). Also called Deneb Kaitos, it is the brightest star in Cetus, despite carrying the designation of beta. (Alpha [α] Ceti, Menkar, is magnitude 2.5.) Although Diphda may not look particularly standout through a telescope, it is certainly strange — according to the late stellar expert Jim Kaler, Diphda’s corona is heated by a strong magnetic field, which causes it to give off exceedingly bright X-rays. Astronomers aren’t sure what’s generating that magnetic field, though, as normally it would come from fast rotation, but this star rotates quite slowly.

Sunrise: 7:04 A.M.

Sunset: 6:30 P.M.

Moonrise: 12:59 P.M.

Moonset: 9:41 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (29%)

Wednesday, October 9

Jupiter is stationary at 3 A.M. EDT this morning, coming to a an apparent stop in the sky some 4° west of Zeta (ζ) Tauri.

If you’re watching the planet through a telescope a bit earlier, around 1 A.M. EDT (midnight on the 8th in the Midwest, and late on the 8th farther west), you’ll note there are three moons visible. Ganymede sits just off Jupiter’s northwestern limb, while Europa (closer) and Callisto (farther) lie to the planet’s east. Keep watching, and Ganymede will close in on the limb, passing behind it around 1:29 A.M. EDT — though its disappearance will take several minutes, so begin watching just before this time. It will re-emerge from behind the planet to Jupiter’s northeast two hours later.

Meanwhile, just after 2 A.M. EDT, Io pops into view just off Jupiter’s northeastern limb, coming out of its own occultation after passing behind the massive world.

While you’ve got your scope out this morning — and with no Moon in the sky — skim some 3.1° east of Jupiter to land on M1, the famous Crab Nebula. This 8th-magnitude smudge of light is the cloud of debris left over after a massive star went supernova, the light from which was seen on Earth in 1054. Now, it houses a tiny, fast-spinning neutron star, called a pulsar, within the expanding tangle of gas and dust. The 6′-by-4′, oval-shaped nebula is bright enough for even small scopes, though light pollution can interfere. Try for it with the largest scope you have, and consider a light pollution or nebula filter.

Sunrise: 7:05 A.M.

Sunset: 6:28 P.M.

Moonrise: 1:57 P.M.

Moonset: 10:38 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (39%)

Thursday, October 10

First Quarter Moon occurs at 2:55 P.M. EDT, making this evening shortly after dark an excellent time to observe our satellite. At First Quarter, the Moon’s nearside appears half-lit, with the terminator separating night and day running right down the middle. Right at the terminator is where shadows are sharpest, creating excellent contrast for observing the features that fall there.

Start near the northern pole of the Moon and slide down just a little way. Do you see a sharp, straight slash through the landscape? That’s Vallis Alpes, a 103-mile-long (166 kilometers) valley that cuts through the rugged Montes Alpes, which curve around to the southwest. At its broadest, this valley is some 6 miles (10 km) wide.

Moving south to near the lunar equator, look for a large, shallow crater with a smaller, round “scoop” taken out of its northeastern floor. This is Hipparchus, some 93 miles (150 km) wide, with smaller Horrocks Crater forming the deep pockmark within it. Look closely at Hipparchus’ western rim as well — here, the rugged terrain has been nearly worn away by numerous impacts that came after the initial crater formed.

Sunrise: 7:06 A.M.

Sunset: 6:27 P.M.

Moonrise: 2:47 P.M.

Moonset: 11:44 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (49%)

Friday, October 11

Pluto stands stationary at 10 P.M. EDT. The tiny, distant dwarf planet is in Capricornus, not far east of the waxing gibbous Moon, which is in Sagittarius the Archer this evening. The region is setting in the west after sunset, so between the low altitude and brightness of the Moon, trying to hunt down the elusive dwarf planet is not a good idea tonight.

Instead, turn your gaze to the east, where Perseus has reached more than 30° in altitude by 10 P.M. local daylight time. In the northwestern portion of this constellation, near its border with Cassiopeia, lies the famous Double Cluster: a pair of open clusters cataloged as h and Chi (χ) Persei (NGC 869 and NGC 884, respectively). Located about 7.5° east-southeast of magnitude 2.7 Delta (δ) Cassiopeiae, the two clusters are easily visible with binoculars or any telescope. In fact, the higher the magnification, the smaller your field of view, which will reduce the number of stars you see. Look through your telescope’s finder scope to see both clusters at once, separated by just 25’ — less than the width of the Full Moon in the sky.

If you do want to increase your magnification, focus in on just one cluster at a time. Both are rich with stars and contain splashes of color, with a few older, redder stars among the bright blue points of younger, hotter stars.

Sunrise: 7:07 A.M.

Sunset: 6:25 P.M.

Moonrise: 3:59 P.M.

Moonset: —

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (60%)

Sky This Week is brought to you in part by Celestron.