Friday, September 22

Mercury reaches greatest western elongation (18°) at 9 A.M. EDT. The solar system’s smallest planet is visible in the early-morning sky just before sunrise for the next several days, though now it will start to sink back toward the horizon earlier and earlier. If you’re up early this week, you can catch it near the hindquarters of Leo, which appear above the eastern horizon in the hour before dawn.

First Quarter Moon occurs this afternoon at 3:32 P.M. EDT. At sunset, our satellite sits just above the spout of Sagittarius’ Teapot asterism, about 1.5° above Gamma (γ) Sagittarii at the very tip of the spout. Its current position also puts the Moon near the center of the Milky Way, and the plane of our galaxy lies just to its northwest.

Now with its face half lit, the Moon is a wonderful target with binoculars or a small scope. Take your time exploring the terminator, which is the line dividing lunar night and day. This is where shadows appear sharpest, bringing out the most detail in the terrain. On the eastern, sunlit half of Luna, look for the bright, rayed crater Stevinus near the southeastern limb. Above it in the northeast are the dark blotches of the Seas of Crises, Tranquillity, and Serenity.

Sunrise: 6: 47 A.M.

Sunset: 6:57 P.M.

Moonrise: 2:40 P.M.

Moonset: 11:26 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (49%)

*Times for sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset are given in local time from 40° N 90° W. The Moon’s illumination is given at 12 P.M. local time from the same location.

Saturday, September 23

Earlier this month, observers saw a new “star” flare up in the galaxy NGC 1097. This is the supernova SN 2023rve, first identified on the 8th and — although now fading — still visible as a point of light in the outskirts of this barred spiral galaxy if your scope is big enough.

The best time to hunt down this transient target is early in the morning, after the Moon has set and the constellation Fornax, which houses NGC 1097, is directly south. This constellation doesn’t get very high for most U.S. observers, so try to set up on a hill or building above your surroundings and minimize any ground light and trees or buildings along your southern horizon.

Admittedly, this observation is likely for more advanced skywatchers: Although the galaxy itself is 9th magnitude and visible with even moderate scopes, the supernova is now around magnitude 15, meaning you’ll need an instrument at least capable of picking up Pluto to view it. Alternatively, long-exposure astrophotos will reveal the explosion’s faint light, as well as some detail in the galaxy’s wispy arms. You’ll find NGC 1097 just over 2° north of magnitude 4.5 Beta (β) Fornacis; the supernova is embedded in the northern arm.

The autumnal equinox occurs at 2:50 A.M. EDT. On this day, the Sun sits directly above the equator and the season of autumn begins in the Northern Hemisphere. (And in the Southern Hemisphere, it is now spring.)

Sunrise: 6:48 A.M.

Sunset: 6:56 P.M.

Moonrise: 3:40 P.M.

Moonset: —

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (60%)

Sunday, September 24

New Horizons and Hubble are teaming up this week to observe the ice giants Uranus and Neptune. NASA has put out a call for amateur astronomers to image the planets and help with the campaign.

Whether you’re an astroimager or not, the ice giants are on display this evening if you want to hunt them down for a look. Let’s start with Neptune, which just passed opposition and rises around sunset and sets at sunrise. Because it’s small and faint, though, you’ll want to give it a few hours to climb away from the horizon. Two hours after sunset, magnitude 7.7 Neptune is 25° high in the east, hanging below the Circlet of Pisces. You’ll need either binoculars or a telescope, as its light is too faint for the naked eye. The planet lies about halfway along a vertical line drawn between 4th-magnitude Iota (ι) Ceti in Cetus and 4th-magnitude Gamma Piscium in the Circlet. Once you’ve homed in on the region, you’ll find the ice giant currently sits just 20′ west of magnitude 5.5 20 Piscium. Neptune’s tiny, bluish disk is just 2″ across and will look like a “flat” star compared to 20 Psc.

Next, let’s move to Uranus. Rising around 9 P.M. local daylight time, by 11 P.M. it’s some 20° high in Aries, located to the lower left (east) of bright Jupiter. The latter is magnitude –2.8, a bright, easy naked-eye object. Uranus, though, is magnitude 5.7 — at the edge of naked-eye visibility and best picked up with optics (binoculars or any small scope will do). Uranus is about 7.8° east of Jupiter, or you can alternatively use the Pleiades star cluster (M45) in Taurus to guide you instead, as the planet is 8.5° west-southwest of this group of young suns. Once you find the planet, you’ll note its disk, too, looks like a “flat” grayish star. It’s about twice as large as Neptune, coming in at 4″ in apparent width.

Sunrise: 6:49 A.M.

Sunset: 6:54 P.M.

Moonrise: 4:30 P.M.

Moonset: 12:32 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (71%)

Monday, September 25

Venus moves into Leo today and sits 11.2° due west of Regulus, which anchors the Sickle asterism that outlines the Lion’s head, in the predawn sky. The bright, magnitude –4.7 planet now appears to hang directly below the Beehive Cluster (M44) in Cancer, as well as (higher up) the two bright stars Castor and Pollux in Gemini. M44 is a stunning sight through binoculars or a low-powered scope; under good conditions, you may be able to make it out without optical aid whatsoever, though give it a try earlier in the morning rather than later. As twilight starts to brighten the sky, the young stars in this open cluster will fade from naked-eye view, though they’ll remain visible under magnification for longer.

Far to Venus’ lower left, also in Leo, sits magnitude –0.6 Mercury. An hour before sunrise, Venus is more than 25° high in the east, while Mercury is just 5° high, much closer to the horizon. Compare the two through a telescope: Venus is a whopping 35″ across, with only 32 percent of its face lit. Mercury is just 7″ across but shows off a 62-percent-lit face. The tiny planet sits nestled close to 5th-magnitude Chi (χ) Leonis, just 3′ northwest of this star early this morning.

Sunrise: 6:50 A.M.

Sunset: 6:52 P.M.

Moonrise: 5:11 P.M.

Moonset: 1:48 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (81%)

Tuesday, September 26

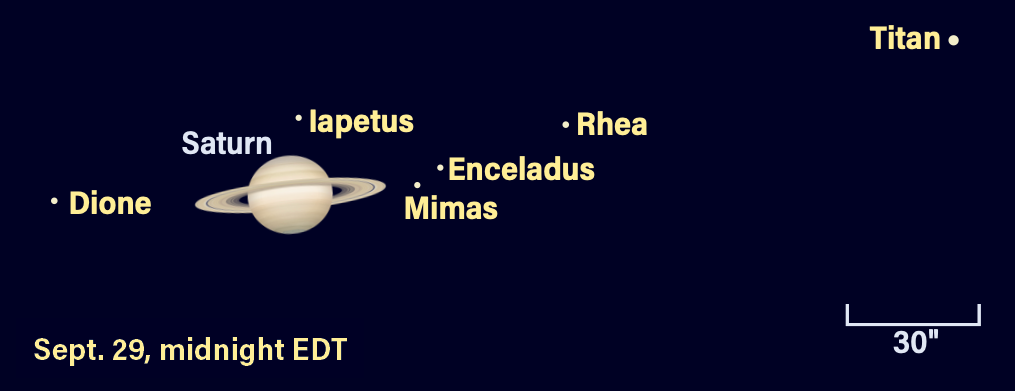

The Moon passes 3° south of Saturn at 9 P.M. EDT, an event visible from most of the U.S., though how high or low the pair appears in the sky will depend on your location. They appear together in southern Aquarius, the Moon now a bright waxing gibbous that hangs between Skat to the east and Deneb Algedi in Capricornus to the west. North of the Moon is magnitude 0.5 Saturn, which will be best seen through binoculars or, better yet, a telescope, thanks to the bright background light thrown out by our satellite.

You may still be able to spot Titan, which lies 2.5′ due east of the planet tonight. Although several fainter moons cluster closer to the rings and disk, their 10th-magnitude glow may be lost amid the moonlight. If you can catch them, Tethys, Dione, and Rhea lie (in that order) in an east-west line, with Tethys to Saturn’s east and Rhea and Dione to the west. The planet’s disk is 19″ across, dwarfed by its 43″-wide ring system, which is tilted 8° to our line of sight, putting slightly more of Saturn’s northern regions than its southern pole on display.

The young, bright star Fomalhaut in Piscis Austrinus lies below the Saturn-Moon pair, much closer to the horizon for those in the U.S. This 1st-magnitude star is surrounded by a huge, planet-forming debris disk that was recently imaged in great detail by JWST.

Sunrise: 6:51 A.M.

Sunset: 6:51 P.M.

Moonrise: 5:45 P.M.

Moonset: 3:07 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (89%)

Wednesday, September 27

The Moon reaches perigee, the closest point to Earth in its orbit, at 8:59 P.M. EDT. At that time, our satellite will sit 223,269 miles (359,317 kilometers) away.

With the Moon brightening in the sky — it’s nearly Full and may even look Full to the untrained eye — we’ll have to concentrate on brighter targets. Today, look north after dark to spot Cassiopeia the Queen, whose constellation often looks like an exaggerated W or M in the sky. We’re looking in the Queen’s far northwestern regions for M52, a 7th-magnitude open cluster of stars about 6° northwest of magnitude 2.3 Caph, also cataloged as Beta Cassiopeiae.

M52 houses some 200 stars, though not many of them are particularly bright. Through binoculars, the cluster will look more like a misty cloud, while a telescope will start to resolve its suns into individual points of light. The cluster spans about 13′ and lies some 5,000 light-years away, though the distance is not well constrained. Some observers note that it has a fan shape reminiscent of the letter V.

M52 is located just over half a degree northeast of the Bubble Nebula (NGC 7635), though the latter requires a larger (8 inches or more) telescope to pick up. The Bubble’s low surface brightness may be hard to see with the Moon throwing out plenty of background light, so if you can’t spot it even in your large scope, make a note to come back during Luna’s waning phases to try to capture this delicate and diffuse structure of gas under darker conditions with better contrast.

Sunrise: 6:52 A.M.

Sunset: 6:49 P.M.

Moonrise: 6:14 P.M.

Moonset: 4:26 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (97%)

Thursday, September 28

The Moon passes 1.4° south of Neptune at 1 P.M. EDT. Recall the ice giant is in Pisces and visible all night, from shortly after sunset to shortly before sunrise, though you’ll need binoculars or a telescope to pick it up and the bright Moon nearby will certainly complicate your ability to spot it. If you do want to try for the distant planet, check out Sunday’s entry for more details on how to find it.

Early risers can enjoy the tableau of well-known winter constellations rising above the horizon before dawn. Some two hours before sunrise, the sky is still quite dark and Canis Major with its bright nose, Sirius, stands in the southeast looking up toward its master, Orion the Hunter, who aims his bow at Taurus the Bull.

Sirius is the brightest star in the sky. If you drop your gaze southeast, you’ll be among the stars that make up the hindquarters of the Big Dog, which is where our target this morning lies: 145 Canis Majoris, also known as h3945 or the Winter Albireo.

What is the “regular” Albiero? This is a bright, beautiful double star in Cygnus the Swan. The pair is revered for its contrasting colors of yellow-orange and blue, which signify the stars’ different temperatures. Hotter stars appear blue-white, while cooler stars appear orange-red, with yellow stars falling in the middle of the temperature spectrum.

Located about 10° southeast of Sirius and 3.5° north-northeast of Wezen (Delta [δ] Cma), 145 Cma is another double star with stunning color contrast. The two suns lie just 27″ apart, challenging (but not impossible) in smaller binoculars but easy with larger ones or any small telescope. The brighter star is magnitude 5 and has a yellow hue, while the fainter companion is magnitude 5.9 but glows a much hotter blue.

Sunrise: 6:53 A.M.

Sunset: 6:47 P.M.

Moonrise: 6:40 P.M.

Moonset: 5:45 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (99%)

Friday, September 29

Full Moon occurs at 5:58 A.M. EDT. Also known as the Harvest Moon, this Full Moon is also a Super Moon, thanks to the phase occurring while our satellite is near perigee. It is the last Super Moon of the year, as the lunar phase and orbital period finally start to diverge enough that by next month the Full phase will no longer coincide closely enough with perigee to meet the definition for a Super Moon.

The Full Moon rises as the Sun sets and remains visible all night, dominating the sky with its bright light. Despite that light, you might want to try catching Saturn’s moon Iapetus as it sits near the ringed planet’s disk late tonight when it reaches superior conjunction. The two-faced moon is brightest (10th magnitude) at western elongation, then fades nearly two magnitudes by the time it makes it to eastern elongation. Around midnight EST (earlier in the night in western time zones), Iapetus lies just 17″ south of Saturn, halfway along its journey and roughly magnitude 11. It will likely be difficult to catch visually, but easier for astrophotographers and those with large scopes. Even if you can’t spot Iapetus, you may see slightly brighter Titan, still about 2.5′ east of the planet.

Sunrise: 6:54 A.M.

Sunset: 6:46 P.M.

Moonrise: 7:06 P.M.

Moonset: 7:01 A.M.

Moon Phase: Full

Sky This Week is brought to you in part by Celestron.