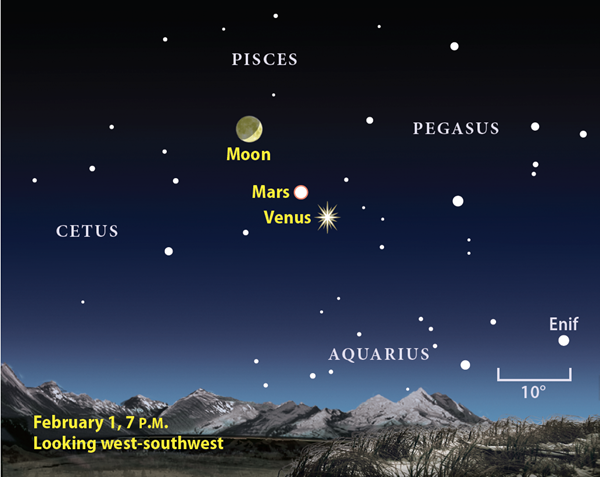

When the sky turns a deep blue after sunset, there’s nothing better to draw you outside than a brilliant gem standing near a crescent Moon. Such a scene awaits viewers February 1 when dazzling Venus appears to the lower right of a five-day-old Moon in the southwestern sky. These celestial jewels, along with Mars, are the key features that change the day-to-day appearance of February’s evening sky.

The approach of midnight adds Jupiter to the mix, while its more distant neighbor, Saturn, graces the morning sky. Finally, once twilight starts to paint the predawn sky early this month, elusive Mercury pops into view. Although these naked-eye objects will command most of your attention, binoculars open up the deeper reaches of the solar system by bringing Uranus and Neptune into range.

Let’s focus our attention on Venus first. This inner world is hard to miss. The planet reaches greatest brilliancy the night of February 16/17, when it shines at magnitude –4.8, but it doesn’t dip below magnitude –4.7 all month.

Venus also appears far from the Sun. The planet rides high in a dark sky and doesn’t set for more than three hours after our star until February’s final few days. Venus’ combination of brightness and altitude allows it to cast shadows under a dark enough sky. Try to see this rare effect after the February 10 Full Moon. If possible, use a blanket of fresh snow as a backdrop to make shadows easier to see.

On February 1, the Moon lies 17° from Venus while Mars stands 5° from the brighter planet. Venus itself resides just east of the Circlet asterism in Pisces the Fish. Both planets drift on a northeasterly path across this constellation during February. The Moon returns to the area on the 28th, though it then appears as a thinner crescent 10° south (lower left) of Venus.

Now is a great time to view Venus through a telescope because both its size and phase change quickly. On February 1, the planet spans 31.3″ and shows a 39-percent-lit crescent. That’s large enough that even steadily held binoculars can reveal the crescent, though it’s best to try in twilight to avoid the glare Venus makes against a black sky.

The planet’s orbital motion carries it more than a half-million miles closer to Earth every day. By the evening of February 15, the planet’s disk has grown nearly 25 percent, to 38.3″ in diameter, while its phase has shrunk to 28 percent lit. By the time the crescent Moon returns to the scene on the 28th, the disk measures 46.9″ across while the Sun illuminates just 17 percent of its Earth-facing hemisphere. Although the changes accelerate further in March, Venus will drop back toward the Sun on its way to inferior conjunction March 25.

If it weren’t for Venus, Mars would be the brightest object in Pisces and the surrounding constellations. The Red Planet shines at magnitude 1.1 in early February and fades slightly, to magnitude 1.3, by month’s end.

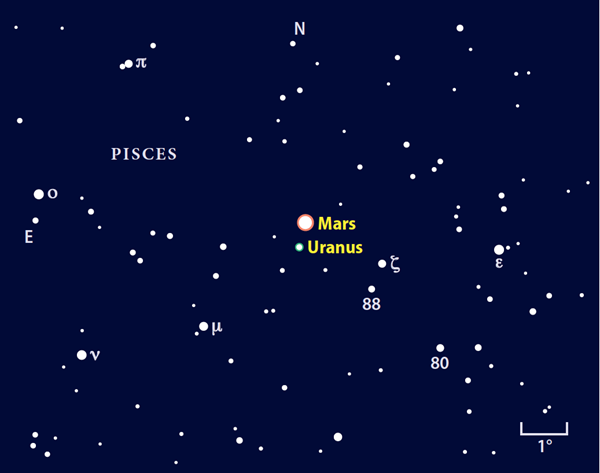

As it cruises across Pisces, Mars passes a smattering of dim and unremarkable stars. But the appeal of its backdrop improves markedly in late February. The ruddy world then pulls near Uranus, offering observers a chance to see both in a single low-power telescopic field of view.

Mars approaches within a 7×50 binocular field of Uranus just after mid-February, but the real show begins on the 25th. The two planets then appear 0.9° from each other. The next evening, Mars passes 34′ north of Uranus. The gap widens to 0.9° again on the 27th, but both still fit in a single low-power field. Mars presents a 4.6″-diameter disk while Uranus, despite lying 10 times farther away, spans 3.4″. Although neither object shows any detail, the orange-red color of Mars contrasts nicely with the blue-green of Uranus.

Without any bright stars close by, Uranus proves harder to find in early February. First, locate magnitude 4.3 Epsilon (ε) Piscium, which lies 14° southeast of magnitude 2.8 Algenib (Gamma [γ] Pegasi), the star at the Great Square of Pegasus’ southeastern corner. From Epsilon, head 2.7° east to magnitude 5.2 Zeta (ζ) Psc. Uranus lies 1° east of Zeta on February 1 and double that distance on the 28th. The planet glows at magnitude 5.9 and shows up easily through binoculars.

The early evening sky harbors one more planet, but you’ll have to hunt for Neptune during February’s first week as the last vestiges of twilight fade away. The ice giant then lies about 10° high in the west-southwest. You can find the magnitude 8.0 planet among the background stars of Aquarius, 1.2° southwest (directly below) magnitude 3.8 Lambda (λ) Aquarii. Neptune descends into twilight and out of view after the month’s first week. It will return to view before dawn in April.

Jupiter rises by 11:30 p.m. local time February 1 and some two hours earlier by month’s end. It appears nearly motionless against the backdrop of Virgo this month, remaining 4° due north of that constellation’s brightest star, 1st-magnitude Spica. At magnitude –2.2, however, Jupiter shines some 20 times brighter than the Maiden’s luminary.

Although Jupiter stands clear of the southeastern horizon by midnight, wait until it climbs high in the south a couple of hours before twilight begins to get the best views through a telescope. Even the smallest instrument reveals Jupiter’s disk, which grows from 39″ to 42″ across this month, and the two dark bands that are the gas giant’s major atmospheric features. These parallel belts sandwich a brighter zone that coincides with the jovian equator.

Also keep an eye out for the Great Red Spot. Although this Earth-sized storm currently appears more orange than red, it becomes obvious when it lies on the hemisphere facing our planet. If you don’t see it, you won’t have to wait long because Jupiter spins on its axis in less than 10 hours.

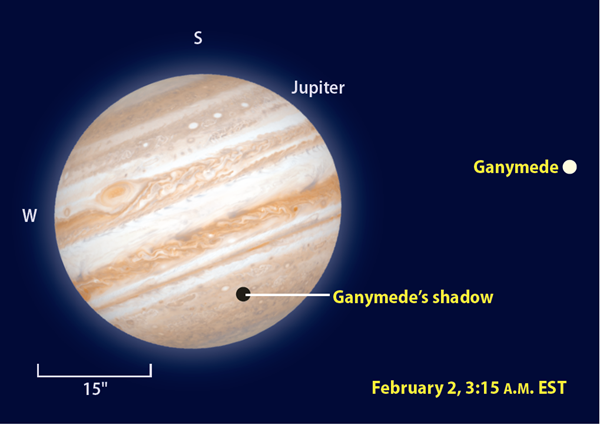

Four bright moons circle Jupiter in periods that range from 1.8 to 16.7 days. Their constant motion means you’ll see a different display every night, and occasionally even from one hour to the next. Pay particular attention when one of these satellites passes in front of Jupiter — you can track its dark shadow crossing the planet followed by the moon itself.

Ganymede, the solar system’s biggest moon, casts a large shadow. The morning of February 2 provides the month’s first chance to see this dark circle. It first appears on Jupiter’s bright cloud tops at 1:51 a.m. EST. It appears most conspicuous when it crosses the planet’s central meridian around 3:15 a.m. Ganymede itself then appears as a bright dot less than a planet diameter east of Jupiter. This scene gives a good sense of the Sun’s angle relative to our line of sight. The shadow transit ends at 4:25 a.m., while the moon itself crosses into Jupiter’s north polar region at 6:43 a.m. This is after twilight begins in eastern North America, but observers to the west will see it in a dark sky.

Ganymede performs a similar sequence of events the morning of February 9, though the timing for this one works out better for western North America. Because the moon revolves around Jupiter every 7.15 days, such transits occur with that frequency. Unfortunately, this means February’s remaining events can’t be seen from our continent.

Io and Europa orbit inside Ganymede, so they offer more transit-viewing opportunities. If you plan to observe the planet around 4 a.m. EST (1 a.m. PST), the best Io events this month occur February 7, 14, and 21. Europa takes the spotlight February 19 and 26.

Our next planet doesn’t rise until the wee hours. Saturn pokes above the southeastern horizon shortly after 4 a.m. in early February and by 2:30 a.m. at month’s close. Look for it an hour or so before morning twilight begins. The ringed planet lies among the rich Milky Way star fields near the border between Ophiuchus and Sagittarius, and it crosses from the former to the latter constellation on the 23rd. By the 28th, its eastward motion has carried it within 4° of the Trifid Nebula (M20).

Saturn shines at magnitude 0.5, noticeably brighter than any star in this vicinity. Swing your telescope to the distant world and prepare to be dazzled. Any instrument reveals the delicate ring system, which spans 36″ in mid-February, wrapped around the planet’s 16″-diameter disk. The rings tilt 27° to our line of sight, affording marvelous views of the dark Cassini Division that separates the outer A ring from the brighter B ring. Small scopes also reveal the 8th-magnitude moon Titan.

Mercury lies on the opposite side of Sagittarius in early February and appears low in the southeast during morning twilight. From mid-northern latitudes on the 1st, the inner world climbs just 5° high a half-hour before sunrise. Use binoculars to find the magnitude –0.2 planet against the brightening sky. A telescope shows Mercury’s disk, which spans 6″ and appears 81 percent lit.

An annular solar eclipse graces the sky across parts of South America and Africa on February 26. During such eclipses, the Moon passes directly in front of the Sun but doesn’t completely cover it, leaving a ring of sunlight visible at the peak.

The eclipse track begins in the South Pacific before crossing the Andes Mountains of southern Chile and the high plateaus of Patagonia in western Argentina. Weather prospects look great for Patagonia, where annularity lasts just over a minute with the Sun 34° above the horizon.

After traversing the South Atlantic, the eclipse path reaches the coast of Angola, about halfway between Lobito and Namibe. Annularity lasts 69 seconds there, with the dramatic ring of fire hanging 16° above the ocean. The eclipse ends at sunset in the southern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS | ||

| Evening Sky | Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Venus (west) | Jupiter (southeast) | Mercury (southeast) |

| Mars (west) | Jupiter (southwest) | |

| Uranus (southwest) | Saturn (southeast) | |

| Neptune (west) | ||

Young and old provide a nice contrast

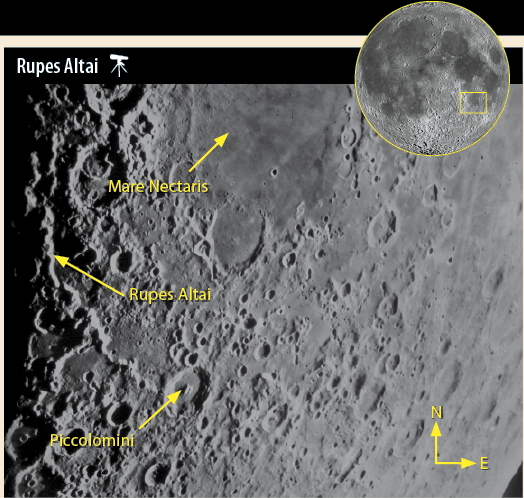

Few sights can compare with the chain of lunar features that hug the day-night terminator on a five-day-old Moon. On the evening of February 1, the large crater Posidonius and the Serpentine Ridge dominate the Moon’s northern half, while the bright-rimmed crater Theophilus will catch your eye just south of the equator.

To the south lie the vast plains of Mare Nectaris (Sea of Nectar). The low Sun angle on the 1st reveals the true extent of the blast that carved out the entire Nectaris Basin. A feature like this is more complex than a simple bowl with a central peak, and much larger than what first greets the eye. The mare, defined by the dark plains of lava that bubbled up from below through cracks in the basin floor, forms just a small part of it.

Rupes Altai (Altai Scarp) marks the true rim of Nectaris. On the 1st, it stands out as a bright arc that disappears at its southeastern end under the more recent crater Piccolomini. The Sun slowly exposes the scarp’s northern section as it climbs higher in the lunar sky over the next few hours.

Sunlight sets solar system dust aglow

Meteor activity remains low during February. The best shower is the minor Alpha Centaurids, which peaks before dawn February 8. But this is strictly a Southern Hemisphere event. Viewers can see up to six meteors per hour once the Moon sets after midnight.

Meteors arise when dust particles enter Earth’s atmosphere and burn up. Similar bits of meteoritic dust pervade the solar system’s plane, and northern observers can view this material in the latter half of February. Sunlight reflecting off these particles creates the zodiacal light, a soft glow visible above the western horizon after evening twilight fades away. The light has a distinct cone shape that lines up with the ecliptic, so you can use Venus and Mars as guides. Look for it starting February 12, once the Moon leaves the evening sky.

February’s feast of icy visitors

When it comes to viewing comets, it seems we experience either feast or famine. The cupboards were bare in late 2016, when observers had to haul out their telescopes to catch a glimpse of any. But February brings a banquet of viewing opportunities. Astronomers expect five of these icy interlopers to glow at 10th magnitude or brighter.

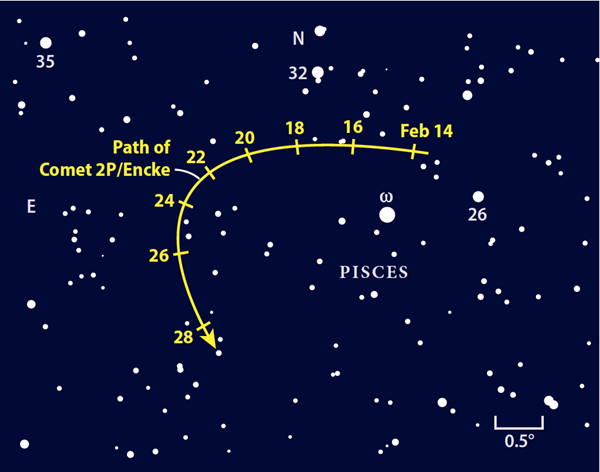

Although several of these will remain visible for at least a couple of months, February is the best window for Comet 2P/Encke. It starts the month in Pisces just a few degrees northwest of Venus. The comet shadows the brilliant planet during the month’s first half, and lies about 5° west of it and near the magnitude 4.0 star Omega (ω) Piscium in mid-February. The Moon has left the evening sky by then, and Encke should be glowing around 8th or 9th magnitude some 20° above the western horizon as twilight fades to darkness.

The comet loops east and then south of Omega in the month’s final two weeks. Although it drops closer to the horizon with each passing day, it also brightens, and should reach 7th magnitude by the end of February. It brightens further in March but quickly disappears in the Sun’s glare. When it returns to view in late March, it will be visible only from the Southern Hemisphere.

German astronomer Johann Encke first deduced that this comet was a periodic object in 1819. It was just the second comet known to make multiple visits to the inner solar system, after its more famous cousin, 1P/Halley. Comet Encke takes only 3.3 years to orbit the Sun, making this its 63rd observed appearance.

Asteroid hunting made easy

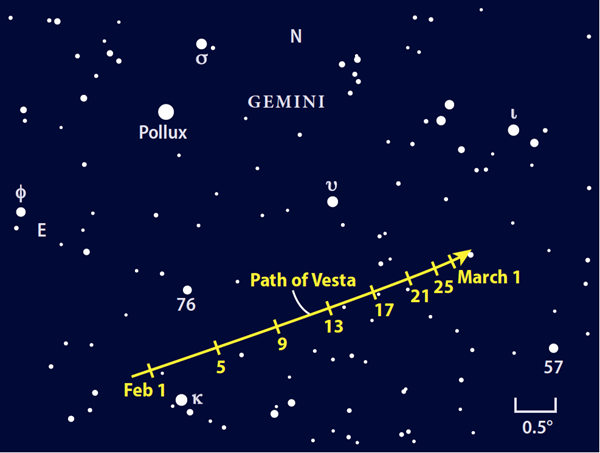

Bright asteroids near bright stars are great — simply grab binoculars, walk outside, adapt to the darkness for five minutes or so, and in another few minutes you’ll be able to nab it. Asteroid 4 Vesta fills the bill nicely this month when it passes near 1st-magnitude Pollux.

First, locate Gemini’s twin stars, Castor and Pollux. They appear halfway up the eastern sky as darkness falls. Pollux shines a bit brighter than Castor and resides closer to Procyon, one of the Winter Hexagon’s other luminaries. Vesta lies half a binocular field from Pollux. The asteroid begins February 3° south of the star and ends the month 4° to its southwest.

Use magnitude 3.6 Kappa (κ) and magnitude 4.1 Upsilon (υ) Geminorum as guides. There aren’t any background stars close to the asteroid that will masquerade as Vesta. On February 6 and 7, it passes just north of a field star half a magnitude fainter.

With a diameter of 325 miles, Vesta is slightly more than half the size of dwarf planet Ceres. But it reflects almost four times more light than the king of the asteroid belt, which makes it the brightest and easiest to find object in the belt.