I

t’s hard to imagine a more spectacular setting: High on the promontory of Cape Sounion, at the southeast tip of the Attica peninsula, stands the Temple of Poseidon, the 5th century B.C. Greek monument that inspired Lord Byron and continues to mesmerise visitors today. The Moon, just past last quarter, hangs in the sky above the blue-green waters of the Aegean. A few fishing boats are moored in the bay, with the island ferries moving silently on the horizon.

Meanwhile, on the grounds of a luxury hotel by the beach, some twenty amateur astronomers anxiously are awaiting Venus’s first solar transit of the century. Most are from the United States; a few are proudly wearing the T-shirts of their local astronomy clubs. At least one couple is from Germany. Most are participants in a tour organized by Spears Travel, with guest astronomer Fred Espenak of NASA, but a number of curious hotel guests and locals also have dropped by.

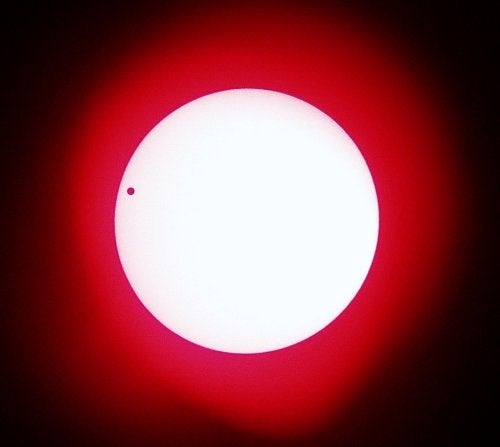

The previous evening had seen substantial clouds, but the morning of the transit dawned without a cloud to be seen — which is, of course, why the group chose this site in the first place. With a clear view more or less guaranteed, the question wasn’t “will we see it” but rather how it would look compared to those old photographs from 1882, or compared to transits of Mercury that several in the group had seen.

Several minutes later, Venus was clearly visible using only a #14 welder’s glass.

“You see pictures of what it’s supposed to look like, but then to actually see it — it’s totally different,” said a woman from Chicago. “It’s like seeing the Parthenon for the first time. It’s awesome.” The view was “fine, very fine,” the man from Germany said, with a very satisfied look on his face.

I don’t know how my 500mm photos will turn out, but just pointing my digital camera into a telescope eyepiece — those with telescopes were more than willing to share, given the leisurely pace of the event — I came away with some dramatic (and surprisingly sharp) images.

The transit, the temple, the sea — it was a day no one here would forget.