![Albireo (Beta [β] Cygni) is a classic example of a double star with contrasting colors.](https://www.astronomy.com/uploads/2024/08/Albireo.jpg)

When we think of color in the night sky, we often think of beautiful images of galaxies and nebulae. Unfortunately, most of the time, their faint, diffuse light shows no color to our human eyes. Stars, on the other hand, have more concentrated light, and there we can see color — even with the naked eye!

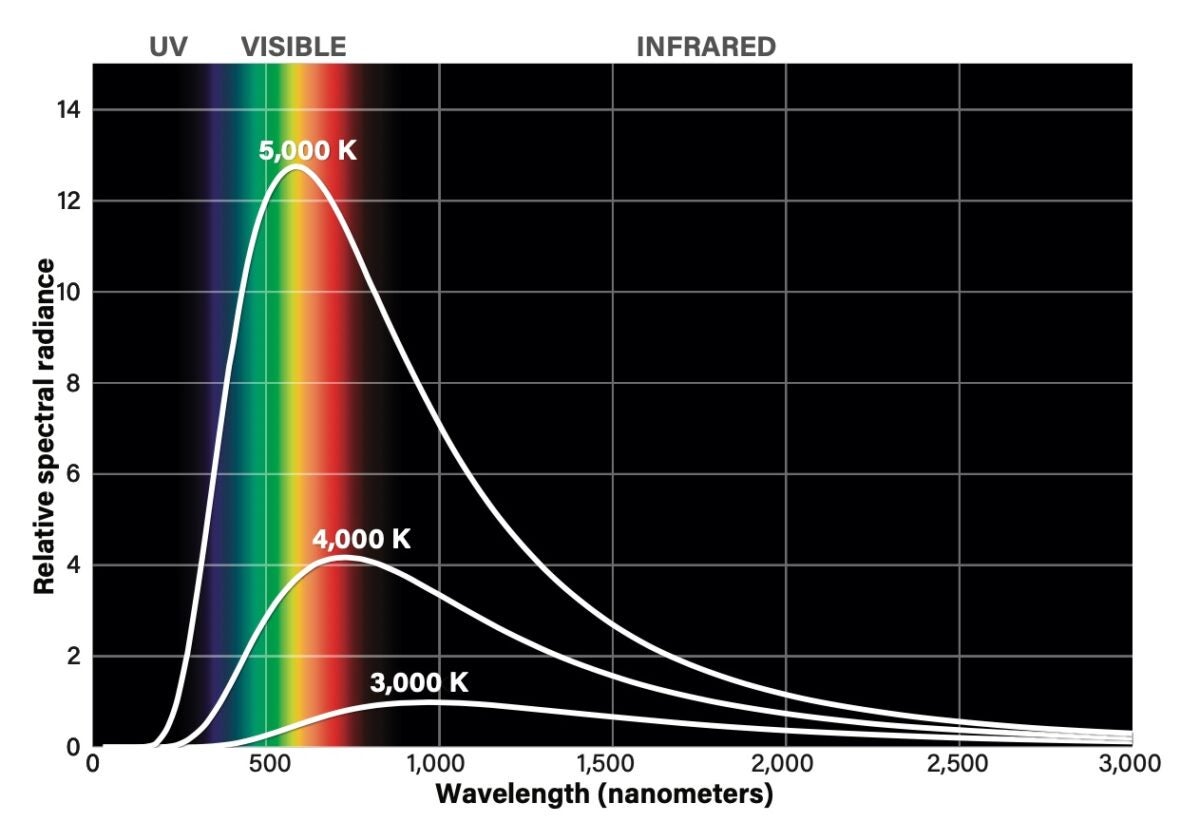

So why do stars appear to have color, and in a variety of hues at that? The short answer is that the temperature of a hot object determines the shape and position of the emitted spectrum. In general, cooler objects peak at redder wavelengths, and hotter objects peak at bluer wavelengths. Think of the flame on a propane stove, which is blue toward the hotter bottom and orange toward the cooler top. The Sun, with a surface temperature of 5,700 kelvins (9,800 degrees Fahrenheit [5,400 degrees Celsius]), peaks in the green portion of the visible spectrum but appears white because the intensity of the red and blue light is nearly as high as the green. Red supergiant Betelgeuse, with a surface temperature of 3,700 kelvins (6,200 F [3,400 C]), peaks in the red and appears orange to our eyes.

For stars, there is a relationship between the color, temperature, size, and chemical composition. You may have heard the Sun called a type G2V star, or that the members of the Pleiades (M45) are hot B-type stars. These are both examples of spectral types. There are six traditional designations for stars: O, B, A, F, G, K, and M.

Type O stars, which are the hottest and bluest, are also extremely luminous; some of the most massive stars are O-type. At the other extreme, M-type stars are by far the most common — they account for 76 percent of the main-sequence stars in our neighborhood. Most M-type stars are red dwarfs, but there are a few notable exceptions. One is the extreme star VY Canis Majoris, a red hypergiant that is the one of the largest and most luminous stars known in the entire Milky Way Galaxy.

Each spectral type is split into 10 subdivisions, which are denoted by adding a numeral. Within each letter class, 0 is hottest and 9 is coolest.

A Roman numeral can also be added to indicate the luminosity class of the star, with I for supergiants, II for bright giants, III for regular giants, IV for subgiants, V for main-sequence stars, VI (or sd) for subdwarfs, and VII (or D) for white dwarfs. This distinguishes a red giant from a red dwarf with the same effective temperature.

You can see star colors in action by checking out the double star Albireo (Beta [β] Cygni), located at the head of Cygnus the Swan. A small telescope or mounted 10×50 binoculars can resolve the pair, with one glowing orange (Beta Cygni A) and one blazing blue (Beta Cygni B). The A star is itself a double star, although not resolvable by amateur instruments. Beta Cygni Aa is a K-type star, with a surface temperature of 4,400 K and a mass of 5.2 solar masses. Beta Cygni B is a B-type star of temperature 13,200 K and is 3.7 solar masses. You can catch Albireo just about all night this month.

Another beautiful color-contrasting pair is the double star Eta (η) Cassiopeiae, located between Navi and Shedar, the two bottom points of the Cassiopeia W. You will need a telescope for this one, but a refractor will do — 64x is enough for a nice view. Eta Cas is slightly more challenging with its four-magnitude difference in brightness between the two stars. Some people see the pair as yellow and red, while some see gold and purple. The brighter of the two is a G0V main-sequence star, very similar to our Sun. Its partner is a K7V main-sequence star. This binary — which lies only 19.4 light-years away — is also visible all night this month.

How many different star colors have you seen? Go out and observe tonight!