More experienced imagers combined RGB-filtered images. However, the exposure times and number of frames collected remained small. Interestingly, imagers often would buy larger instruments and more sensitive cameras before increasing the exposure duration and number.

When I accommodated visitors at Kitt Peak National Observatory as part of an observing program I developed that ran from 1996 to 2005, I spent countless hours manually removing these “vermin” from pictures while guests often fell asleep behind me. After all, guests expected to go home with pretty pictures by the end of a night! As I used Photo-shop’s “Clone” tool (and later the “Healing” brush), visitors often would be concerned that I might erase a galaxy rather than a cosmic ray.

Because of the particle nature of light, the number of photons a CCD chip detects fluctuates with each exposure. If the average intensity of a star on a specific pixel is 1,000 counts (brightness units), then in the first exposure I might measure 943 counts, and in the next exposure it may be 1,078 counts. So, if I take enough exposures and average them together, the resulting value will be a good approximation of the intensity. Unfortunately, we never know what this average value should be beforehand. That’s why we need to make many measurements to find the average (or mean) value.

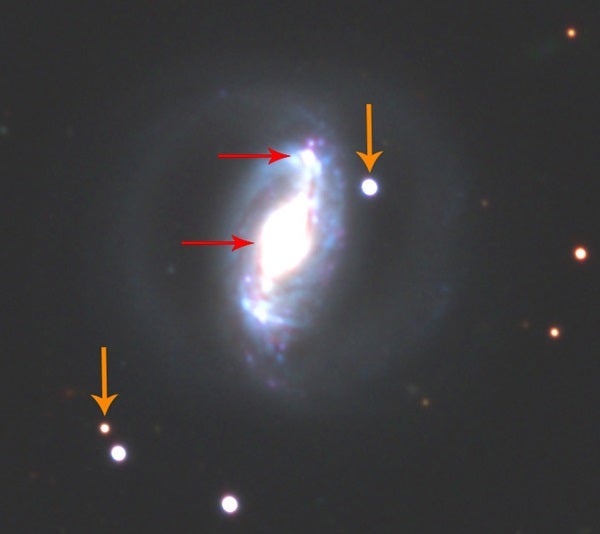

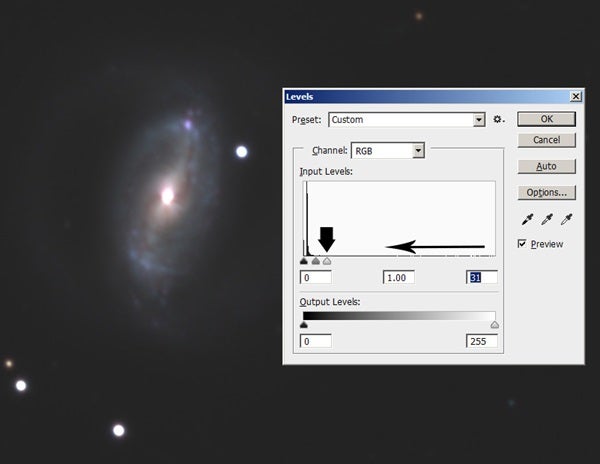

Image #2 shows a real-world example. The left side is a single measurement, and the right half is the average of 20 values at each pixel for a strange planetary nebula called WeBo 1. Closer inspection shows some bright blips in the single exposure that are not in the average image. Most of these are cosmic rays, which represent values we do not want to include when calculating the mean of a set of measurements.

In Image #3, a cosmic ray (a white pixel) was part of the fifth measurement. It contaminated the resulting mean value for that pixel, and it degrades the image quality. What we want to do is identify such outlying values and not use them when calculating the mean.

This means that for the 20 values measured at a particular pixel in the WeBo 1 image, if a cosmic ray activated that pixel, we should reject that value and calculate the mean from the remaining 19 values. This greatly improves the image quality and eliminates transient signals in our images.

In my next column, we will look at how to measure the average amount of fluctuation and then identify these outlying values.