When using my astronomy software or looking at various books, I notice that not everyone draws the constellations the same way. Why?

John Hinkamp

Andros Island, Bahamas

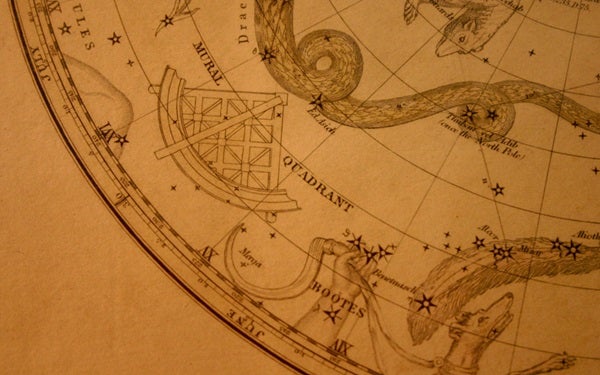

Imagining familiar images in the sky has always been an easy way to track the annual progress of the stars. Around the second century C.E., the Greek astronomer Claudius Ptolemy listed 48 “official” constellations in his book Almagest. No original copy of Almagest has survived, so we don’t know how he connected the stars to form shapes. By the 16th century, European explorers were adding new constellations to fill in their charts. In the late 1670s, Edmond Halley, of comet fame, placed a large oak tree on one of his charts to honor Charles II of England and the Royal Oak behind which he supposedly hid following the Battle of Worcester. That constellation, along with many others, quickly fell into disuse.

One of the most influential star atlases is Johann Bayer’s Uranometria, produced in 1603. It was the first to cover the entire celestial sphere. Bayer set the standard for the classical images we associate with the constellations today.

However, there was no rule for what stars were included in a constellation. All star maps used wavy lines to encompass not only the classical images, but all the faint stars in any given constellation. Then in 1928, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) imposed boundaries based on lines of right ascension and declination, splitting the celestial sphere into 88 regions that constitute the modern constellations. The IAU did not set standards for the star patterns of the constellations, however. Even in the 21st century, star-map makers have artistic license to connect the dots as they see fit.

So, no two sets of maps will ever appear exactly the same. You can even make up your own constellation shapes, as long as they stay within the designated IAU boundaries. Orion still looks like a big butterfly to me.

Raymond Shubinski

Contributing Editor

This question and answer originally appeared in the February 2011 issue.