Solar flares, powerful bursts of energy from our Sun, can have serious effects here on Earth. Flares and other solar eruptions can affect radio communications, disrupt electric power grids, mess up navigation signals like GPS, and pose risks to spacecraft and any astronauts in them. These effects happen because the ionosphere (Earth’s upper atmosphere, from roughly 30 to 600 miles [40 to 965 kilometers] above the surface) absorbs the X-ray and ultraviolet energy emitted — lucky for us. But absorbing so much energy causes it to become charged enough to interfere with devices that use electricity.

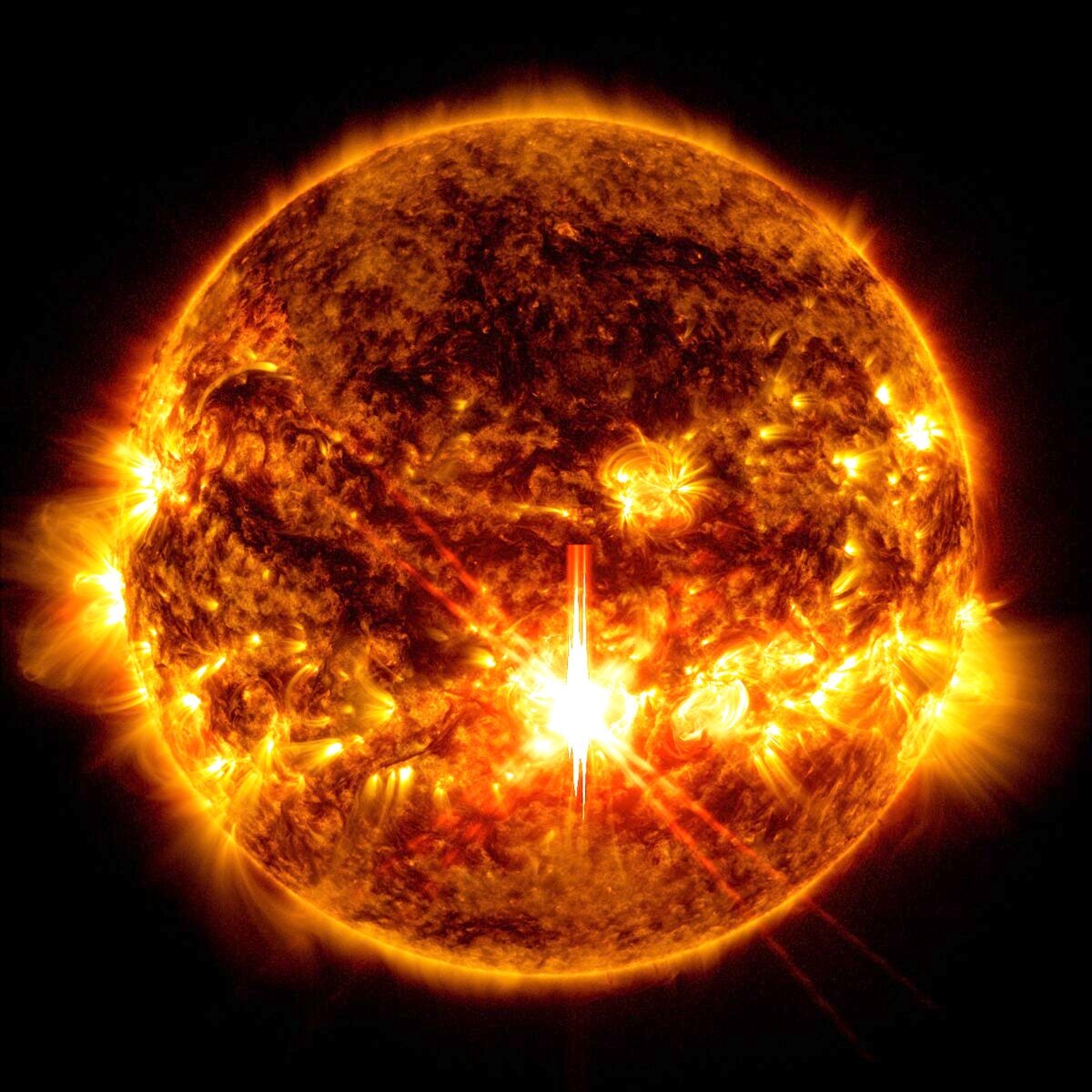

On Thursday, October 3, the Sun emitted an intense flare, which was at its strongest at 8:18 a.m. EDT. Solar physicists classify this flare as an X9. X-class denotes the most intense flares, while the number provides more information about its strength. So, an X9 is a powerful flare.

Solar flares often cause coronal mass ejections. A CME, as it is abbreviated, contains plasma, which is made of charged particles. NASA did not report a CME associated with the new solar flare. But if there is one, and if it’s headed toward Earth, it could create displays of northern lights (or southern lights if seen in the Southern Hemisphere). Astronomers call these glowing lights the aurora borealis (or aurora australis).

Can we expect aurorae?

The radiation from a solar flare travels at the speed of light, so it reaches Earth a mere 8 minutes after the event. Particles in a CME, however, move slower. It can take as much as several days for them to reach us. On October 3, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) issued a geomagnetic storm watch from October 4 to 6, in anticipation of a possible pair CMEs. Although only minor — and mitigable — effects on any technology are expected, the watch notes that aurorae may be visible over northern U.S. states, as well as parts of the Midwest.

So, especially if you live at a latitude north of 35° north (or south of 35° south), be on the lookout for auroral displays the next couple of nights. The Moon will be a thin crescent that will set within a few hours after sunset, so its light won’t interfere with the view. And you can check the latest aurora predictions on the SWPC’s aurora dashboard here. (Note all times are given in UTC, which you will need to convert to your local time.)

Good luck!