After decades of searching, astronomers discovered the first definite brown dwarf only 10 years ago. Now, a new analysis of Hubble Space Telescope data implies our galaxy has almost as many of these failed stars as it does normal stars like the Sun.

The Sun and most other stars power themselves by converting hydrogen into helium. In contrast, brown dwarfs have so little mass — less than 8 percent of the Sun’s — they never get hot enough to sustain this nuclear reaction. Instead, they convert gravitational energy into heat, glowing red, then fade as they cool.

The brown-dwarf candidates belong to the thin disk, the galaxy’s brightest component, which harbors the Sun and most other nearby stars. The thin disk is about 2,000 light-years thick; the brown-dwarf candidates are in a disk that’s 2,280 ± 330 light-years thick.

Extrapolating from the number of brown dwarfs they discovered, Ryan and his colleagues estimate the galaxy has roughly 100 billion L- and T-type dwarfs. This number is comparable to the Milky Way’s total of all other stars put together.

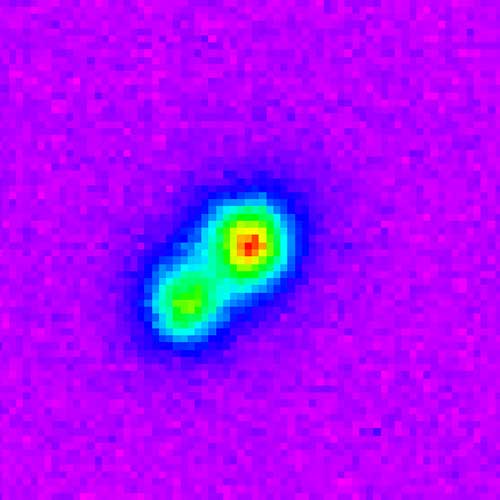

Thus, several brown dwarfs probably lurk unseen within just 12 light-years of the Sun. This volume of space contains more than two dozen main sequence stars like the Sun — but only two known brown dwarfs. Both these brown dwarfs orbit the orange dwarf star Epsilon (ε) Indi, which is 11.8 light-years from Earth. They are the closest known brown dwarfs to the Sun.

Despite their impressive number, brown dwarfs add little weight to the galaxy and do not account for its dark matter. Ryan’s team estimates brown dwarfs contribute roughly a billion solar masses to the Milky Way — only 0.1 percent of the galaxy’s total. Altogether, the galaxy has roughly a trillion solar masses, most of which is dark matter.

Ryan and his colleagues will publish their work in a future issue of Astrophysical Journal Letters.