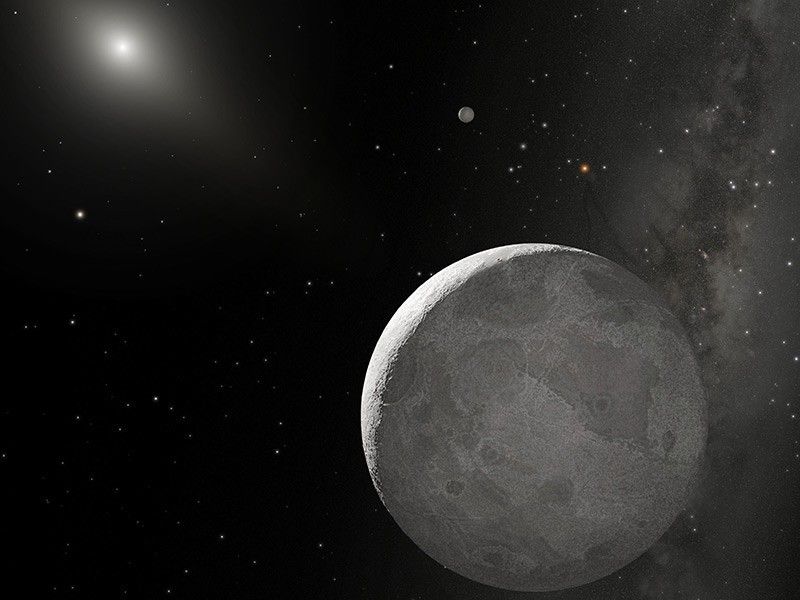

Eight billion miles (14 billion kilometers) from Earth, at the solar system’s ragged edge, lies Eris — a planet-sized oddball of a world that emerged unexpectedly from the darkness 20 years ago. Named for the capricious Greek goddess of discord, trouble-stirring Eris would doubtless be pleased that her celestial namesake caused even mild-mannered astronomers to quarrel, as its discovery caused the nature of what constitutes a “planet” to rear its controversial head.

With a magnitude of 18.7, Eris currently lies in the southern constellation Cetus the Whale, barely resolvable even by the world’s largest telescopes. Due to its vast distance — some 95.6 astronomical units (AU; 1 AU is the average Earth-Sun distance) — its slow apparent progress across the sky makes it notoriously difficult to spot.

At Eris’ distance, the Sun appears as a tiny star in the coal-dark sky, its light taking 13 hours to traverse the space between them and weakly illuminate a glistening surface of methane and nitrogen ices. Eris is three times more distant than Pluto. And its relationship to Pluto — a world demoted since 2006 from the solar system’s ninth planet to a lowly dwarf planet, in large part due to the discovery of Eris — remains contentious today.

A distant find

In 2001, astronomers at Palomar Observatory in California began systematically seeking planet-sized objects beyond Neptune. This time-consuming process targeted small pockets of the sky, utilizing powerful imaging software to identify anything that moved against the starry backdrop. To limit the number of false-positive data returns due to image resolution, the software excluded anything moving slower than 1.5 arcseconds per hour.

“Things like Eris were precisely what we were looking for when we started this survey in 2001,” says Mike Brown of the California Institute of Technology, who co-discovered Eris with Chad Trujillo, then of the Gemini Observatory, and David Rabinowitz of Yale University. “At that time, nothing had ever been found beyond about 60 AU, so we tuned the survey to concentrate on this area.”

But an ironic consequence was that images of the slow-moving Eris, taken by Brown’s team with the 48-inch (1.2 meters) Samuel Oschin Telescope at Palomar on Oct. 21, 2003, slipped entirely through the net, falling below their speed cutoff.

In the months that followed, several new trans-Neptunian objects — bodies whose orbits have an average distance beyond that of Neptune — were discovered: red-hued Sedna in November 2003 and ellipsoid-shaped Haumea in December 2004. Sedna’s 11,400-year orbit carries it to an aphelion (its farthest point from the Sun) well beyond the heliopause, the region near the solar system’s periphery where the Sun cedes gravitational influence to the interstellar medium.

At the time of its discovery, Sedna lay at 90 AU — 8.3 billion miles (13.3 billion km) from the Sun, three times more distant than Neptune. And significantly, it moved at a paltry 1.75 arcseconds per hour. That prompted Brown’s team to reanalyze their older data with lower limits on angular motion, then painstakingly sort through previously excluded images by eye.

“When we found Sedna in 2003 at close to 90 AU and just barely at the limit of our software, we wondered whether we might have missed something even further away,” Brown remembers. “It took months of additional work and processing, until suddenly Eris pops out of the data! In the end, it was the only extra object we found from all of the reprocessing — but worth it!”

The team’s reanalysis finally pinpointed Eris on Jan. 5, 2005. At that time, it was simply called 2003 UB313. Brown excitedly called his wife, Diane, with the news: “I found a planet!”

But his words were ominously propitious, as unfolding circumstances on Earth quickly overtook the discovery.

More planets?

Early observations hinted that Eris might be bigger than Pluto, whose own size remained uncertain until the New Horizons spacecraft flew past in July 2015.

But whether larger or smaller than Pluto, hopes that Eris might also be granted planetary status were quickly dashed. For years, astronomers had hotly debated Pluto’s planethood. Our then-ninth planet was smaller than any other planet, yet carried profound cultural connotations, endearing itself to generations who had grown up reciting the same solar system mnemonic in the classroom and universally accepted it as the ninth planet.

That long-held popular belief was turned on its head with the discoveries of Haumea, Sedna, Eris, and — a few months after Eris — Makemake in March 2005, forcing the astronomical community’s hand. In August 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) formally defined a “planet” as an object circling the Sun, sufficiently large and gravitationally massive to attain a spherical shape, and has cleared its region of space.

Under that definition, the new discoveries fell short on this third point, for none had cleared their respective celestial neighborhoods. But neither had Pluto. On Sept. 6, 2006, Pluto and the others were formally recategorized not as planets but as “dwarf planets” — objects orbiting the Sun that could achieve sphericity but were gravitationally incapable of dominating their environs.

“We knew that second that we found it [Eris] that our concept of the solar system was going to have to change,” says Brown. “We were either going to have to add new planets or subtract one. I would have predicted the former, but even though it means I lost my chance to be called the discoverer of a few new planets, I am delighted that astronomers had the nerve to make the right choice and realize that Pluto should never have been called a planet in the first place.”

What’s in a name?

On Sept. 13, 2006, 2003 UB313 was formally named Eris. But this had not been the original choice. One unofficial name used by Brown’s team was Xena, honoring the titular character in the television show Xena: Warrior Princess — which coincidentally also began with an X, for what might have been the tenth planet.

“We called it Xena right away, just as one of our internal code names,” says Brown. “But when the final IAU decision came out, we decided to search for something in the Greek or Roman mythology to honor the fact that Xena had been something like a real planet for a good year. Not surprisingly, almost everything had been taken by various nondescript asteroids over the years.”

Popular suggestions rounded up in a survey by New Scientist ranged from Persephone to Pax, Galileo to Xena, Rupert to Nibiru, and Cerberus to Loki. The survey results even included the comically floated “Bob” as an option, its originator quipping that it was easily pronounceable, non-offensive, and “I think Uranus needs a break, don’t you?”

“But everyone seemed to have avoided the goddess of discord and strife,” whose Greek name was Eris, recalls Brown. “As soon as we saw it, we realized [it] was perfect.” Just like the strife-inciting goddess of ancient Greece, the celestial Eris had prodded its own hornet’s nest of debate both in the astronomical community and among the wider public.

It turns out that Eris is slightly smaller than Pluto, with an equatorial diameter 1,445 miles (2,326 km) and a surface area roughly equivalent to South America. But Eris is some 27 percent more massive than Pluto, likely due to a denser, rocky interior.

A tiny moon, named Dysnomia after the mythological Eris’ daughter and the goddess of lawlessness, was discovered in September 2005 by Brown’s team at Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. Dark as coal, one-third the size of Eris, and icy in nature, Dysnomia orbits every 16 days at a distance of 23,200 miles (37,300 km).

Eris’ plain white façade reflects some 96 percent of the Sun’s light, making it one of the solar system’s brightest surfaces. Its highly eccentric orbit carries it around the Sun every 559 years, bringing it as close as 37.9 AU (3.5 billion miles [5.6 billion km]) and carrying it as far as 97.5 AU (9.1 billion miles [15 billion km]). Surface temperatures hover around 42 kelvins — about –384 degrees Fahrenheit (–231 degrees Celsius).

Its ubiquitous brightness is matched only by Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus, but Brown does not believe cryovolcanism or geysers are necessarily responsible. “Eris is sufficiently cold that its atmosphere will be condensed onto the surface and I think that is really all that is going on,” he says. “Presumably as Eris gets closer to the Sun, the frosts will sublime and the surface will darken.”

Having passed its most recent aphelion in 1977, Eris will reach perihelion in 2257. Plans for a flyby mission are being considered, with the most ideal launch opportunities in 2032 and 2044. Should such a mission take place, the spacecraft could reach Eris roughly 25 years after launch.

And new discoveries would surely follow.

Related: Does Planet Nine exist?