The third brightest object in the sky after the Sun and Moon, Venus is known for its opalescent splendor at dawn or dusk. Humans have long been drawn to its exquisite beauty and tied it to goddesses of love — from Inanna of Mesopotamian myth to the Greek Aphrodite and Roman Venus.

But Venus is not easy to love. Since 1961, nearly 50 missions from the U.S., Russia, Europe, and Japan have launched to Venus. Some never left Earth orbit. Others circled the planet or simply flew by as they gained gravitational boosts to other destinations. A few alighted on its rocky surface.

In 1990, NASA’s Magellan arrived in orbit around the second planet, using radar to peer through Venus’ clouds and map her tortured terrain for the first time. For four years, it circled the world, revealing a new world to scientists and the public. And, 30 years later, its enormous trove of data is still providing new insights, including tantalizing clues that Venus is still an active world.

Long road to launch

Early Venus exploration was plagued by launch and orbital failures. When the Soviet Venera 8 mission finally managed a soft landing on the surface, it operated for less than an hour before succumbing to the scorching temperatures and crushing pressure of Venus’ atmosphere. Other Venera probes also landed and returned data, but none survived long. Soviet and U.S. orbiters or flyby probes took crude radar images of the surface but could not comprehensively map venusian geology on a global scale.

That was set to change in 1977, with plans for a Venus Orbiting Imaging Radar (VOIR) for high-resolution mapping to study volcanism, cratering, and tectonic activity. VOIR would also measure Venus’ gravity field and interior. But its hefty $500 million price tag precipitated its cancellation in 1982.

A stripped-down Venus Radar Mapper (VRM) using proven technologies and spares from earlier missions was proposed to cut costs. In 1986, VRM was renamed Magellan for the 16th-century Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, first to circumnavigate the globe. Like its Age of Sail namesake, Magellan would unveil a new world for its patrons. Targeting a space shuttle launch in 1988, it would reach Venus in three months.

But Magellan’s fortunes shifted in January 1986, when Challenger exploded after liftoff, killing her crew and grounding the shuttle fleet. Although not implicated in the tragedy, the Centaur-G Prime booster meant to propel Magellan to Venus was canceled on safety grounds. In its stead, NASA substituted the Inertial Upper Stage — a less-powerful booster that would stretch Magellan’s trans-Venus cruise to 15 months.

On May 4, 1989, Magellan finally launched in the payload bay of shuttle Atlantis. It was released into space six hours later. For Atlantis’ crew, it was a relief to see Magellan gone — the longer it stayed aboard the shuttle, the more chance existed for problems to develop. “Get rid of this thing,” joked astronaut Mary Cleave. “First day, it’s outta there!”

Making it to the masked planet

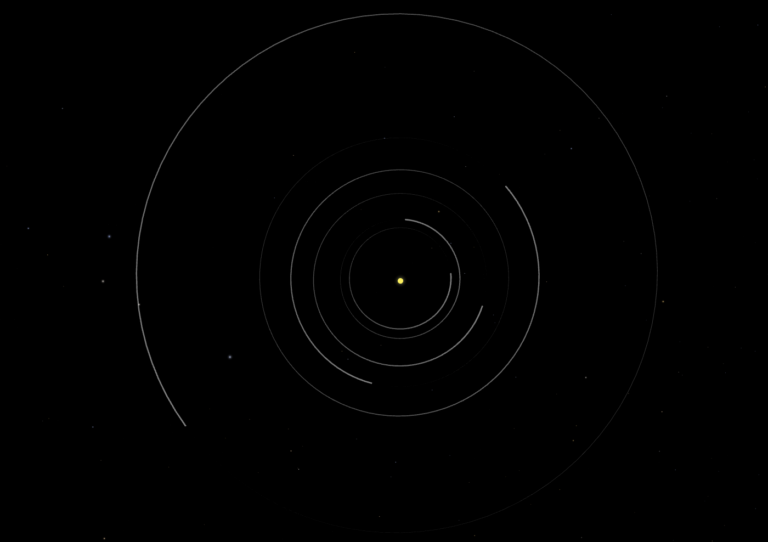

Magellan zipped to Venus at 71,000 mph (113,600 km/h), traveling 1.5 times around the Sun and covering 788 million miles (1.2 billion kilometers). Compared to the launch issues, the cruise was uneventful.

On Aug. 10, 1990, Magellan fired its thrusters for 83 seconds, causing the spacecraft to be captured into a highly elliptical orbit around Venus, with a periapsis (or nearest point to the planet) of 186 miles (300 km) and an apoapsis (or farthest point) of 5,300 miles (8,500 km).

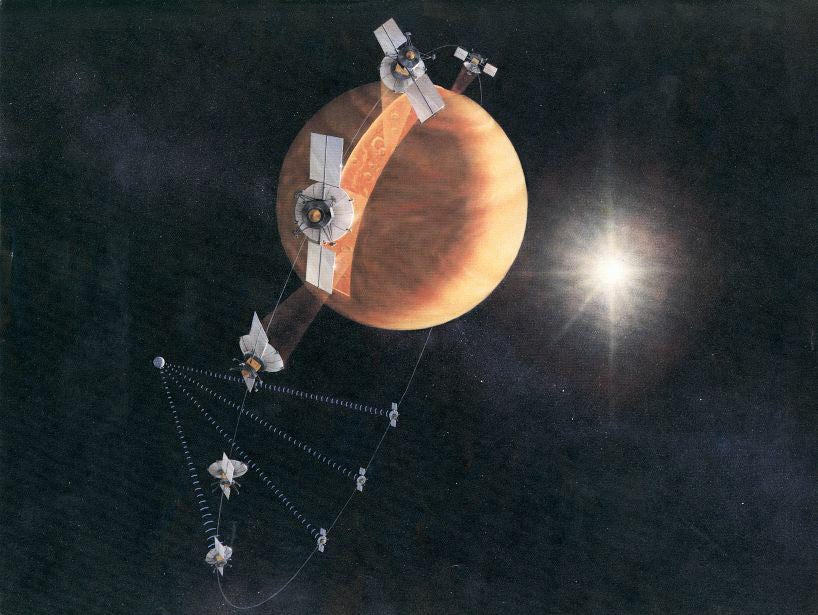

Magellan’s task was nothing less than to map almost all of Venus’ surface at spatial resolutions of 31 miles (50 km) and vertical resolutions of 330 feet (100 meters). And it would image surface features just 0.62 mile (1 km) across.

Built by Martin Marietta with radar provided by Hughes Aircraft, Magellan was managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Its 12.1-foot (3.7 m) antenna saw dual usage for radar mapping and communications — it could transmit 268.8 kilobits each second, the highest data rate of any planetary mission at that time. Scientists readied for the data flood.

Down to business

Magellan’s first mapping cycle from September 1990 to May 1991 imaged 83.7 percent of the surface, achieving resolutions as fine as 300 feet (100 m) — 10 times sharper than ever before. Key finds included the Australia-sized continental upland Ishtar Terra, which runs two-thirds of the way around the planet, and the 36,000-foot (11,000 m) Maxwell Montes, a peak taller than Mount Everest, with slopes possibly dusted with iron pyrite.

Magellan found few impact craters, suggesting a young surface less than 800 million years old. It saw no evidence of Earth-like plate tectonics, but networks of global rift zones and mysterious coronae — giant, localized volcanic hotspots, oval-shaped and ringed by ridges or troughs. Coronae vary from 100 miles (160 km) to over 600 miles (1,000 km) wide and might provide a mechanism for Venus to vent its internal heat.

Ground-based radar images and spacecraft data had hinted at widespread volcanic activity at equatorial and northern latitudes. But Magellan found Venus’ volcanism is ubiquitous, with 85 percent of the surface coated in volcanic matter — from snaking lava flows to high volcanic domes 2,500 feet (750 m) tall and 15 miles (25 km) wide.

The mission’s second mapping cycle, from May 1991 to January 1992, expanded coverage to 96 percent of the surface. Geological features were imaged from different angles to permit observations of ongoing surface processes, and Magellan discovered Baltis Vallis, the longest channel in the solar system — at 4,200 miles (6,800 km), it is a little longer than Earth’s longest river, the Nile.

Wrapping up

The third cycle from January to September 1992 increased coverage to 98 percent and began stereo imaging for three-dimensional mapping, notably of Maxwell Montes. For the fourth cycle, from September 1992 to May 1993, Magellan’s periapsis was lowered to 111 miles (180 km) to measure Venus’ gravity field.

Over 75 days from May to August 1993, the craft intentionally dipped into Venus’ upper atmosphere to tweak its orbit from highly elliptical to near circular. This so-called aerobraking shortened Magellan’s orbital period from 189 minutes to 94 minutes and enabled high-resolution gravitational mapping of Venus’ poles.

The mission’s final phase in August 1993 completed gravitational mapping of 94 percent of the surface and also brought to a close radio science investigations. In September 1994, a week-long “windmill” experiment saw Magellan utilize its solar arrays to acquire valuable aerodynamic and atmospheric data.

The end came in October 1994, when Magellan reduced its periapsis to 86.6 miles (139.7 km) to gather aerodynamic data at lower altitudes. Contact with Earth went dead early on Oct. 12 — the final curtain call for one of the most successful missions in the annals of space exploration.

Legacy well earned

Having mapped 98 percent of Venus’ terrain, Magellan entered the public consciousness for creating more detailed land imagery of our planetary nextdoor neighbor than is available for our own world. Over 50 months and 15,032 orbits of Venus, the spacecraft mapped a surface area three times larger than all of Earth’s landmasses combined.

It also helped facilitate missions that followed and missions that are still yet to come. The aerobraking pioneered by Magellan was used by Europe’s Venus Express orbiter. And radar remains integral to the science toolkits of multiple spacecraft set to fly later this decade or early next — including Russia’s Venera-D mission, NASA’s VERITAS, and India’s Shukrayaan.

Magellan’s scientific legacy also continues to resonate. In 2023, Magellan data reinforced arguments that coronae help cool Venus’ interior where the lithosphere is at its thinnest. Analysis and reappraisals of Magellan results also pinpointed changes to the Maat Mons volcanic vent, which dramatically doubled in size and changed shape over eight months in 1991, with tantalizing hints of lava drainage along its flanks. And in May 2024, old Magellan data indicated lava flows between 1990 and 1992 near the shield volcano Sif Mons, which perhaps generated enough molten material to fill 36,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

These results show that Venus is not a dull, dead world, but one that appears volcanically active to this day. And, three decades after its end, Magellan continues to radiate insights into this geologically and volcanically active world.

Related: Venus likely has active volcanoes, flowing streams of lava