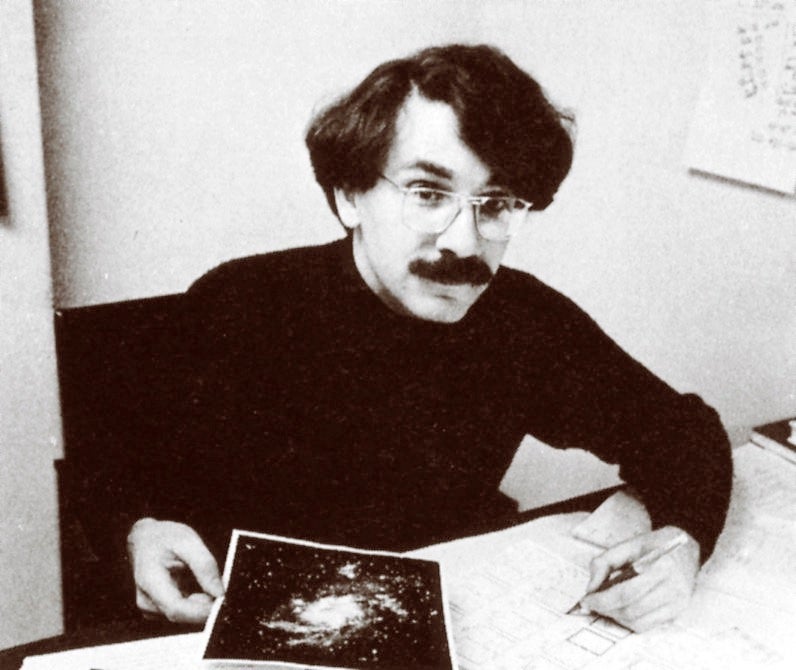

In mid-September 1982, I arrived at our little stone building at AstroMedia Corp. in Milwaukee for my first day of work. I had no idea what adventures awaited. I was hired as the junior assistant editor of Astronomy magazine, and I couldn’t have been more excited. Straight from Miami University in southwestern Ohio, I brought the observer’s magazine I had started in high school, Deep Sky, with me. I was 21, wide-eyed, and ready to explore everything the astronomy world had to offer — and to report on it too.

This year we celebrate Astronomy’s 50th anniversary. I’ve been on the staff for only 40 of those years, but I’ve seen the majority of the history of this title.

First issues

The magazine was founded on May 27, 1973, by Stephen Walther, a 29-year-old astronomy enthusiast who began the venture several years earlier as an experiment in college. His brother, David Walther, was a Milwaukee attorney who supported the publication’s launch. Steve put together a dynamic staff of young, enthusiastic writers and editors, and the first issue appeared in August 1973, with a speckle interferogram of the star Betelgeuse on the cover.

Steve commenced publishing Astronomy because he felt the long-established Sky & Telescope was too technical for most beginners in the astronomy hobby. In time, both magazines would cover the spectrum well and coexist for decades.

The first issue checked in at 48 pages. But the title grew in size and rapidly in circulation. In the summer of 1976, with momentum rocking, Astronomy published an oversized “History of American Astronomy” issue and Steve decided to throw a big party for contributors and friends at a lakeside conference center in Milwaukee. Beside a pool, drink in hand, he collapsed. The next day he was diagnosed with an aggressive brain tumor, and he died about a year later.

Picking up steam

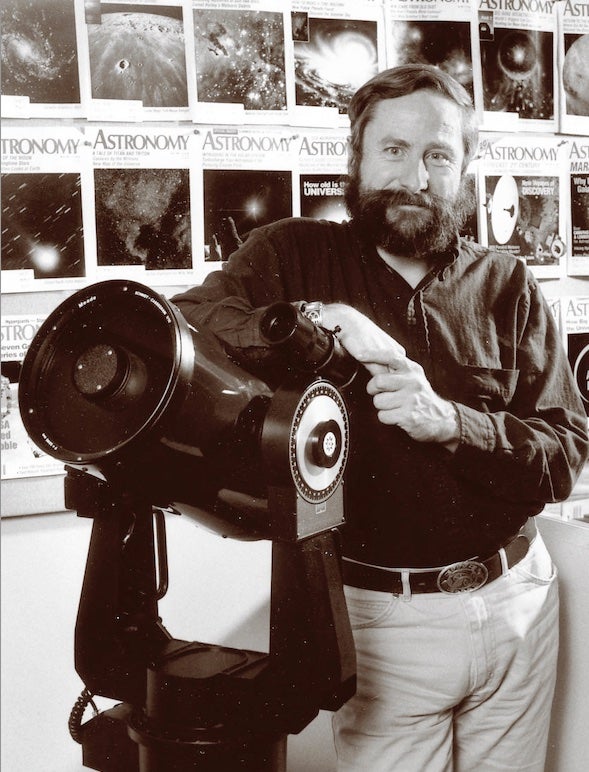

The earliest team was small. The magazine established an office in Milwaukee, first on Broadway and then nearby on Mason Street. Terry Dickinson briefly joined the staff as editor to support Steve, as well as Managing Editor Penny Oldenburger, Assistant Editor Ray Villard, Art Director Craig Brown, and a few others. After Steve’s diagnosis, Richard Berry joined the staff as technical editor, and would become the magazine’s chief driving force for a decade and a half. He became editor and worked as such until 1992.

Under Richard’s leadership, the editorial focus of the magazine sharpened. This was also a bit of a golden age for astronomy, with the afterglow of the Apollo era still alight. In 1975 and ’76, Comet West (C/1975 V1) dazzled observers, the Viking landers explored Mars, and the launch and anticipated discoveries of the Voyager missions had everyone abuzz. Henry Phillips joined the staff as an associate editor; tragically, soon thereafter, he also died young. Robert Burnham and Dewey Schwartzenburg came on as associate editors.

Astro events were cooking and by 1981, when big stories rolled in from the Voyager results, Astronomy exceeded the old standby, S&T, in circulation. It has been the largest-circulation publication on the topic ever since. The group also began publishing Odyssey, a children’s magazine about the universe. Expanding, it moved into a Lannon-stone building on St. Paul Avenue in Milwaukee, a structure that also served as David Walther’s law office, adjacent to the Summerfest grounds. Previously, it had been a bar that occasionally featured mud wrestling.

Great times

When I arrived in 1982, the hobby of astronomy was booming. Star parties and astronomy conventions were at record levels, and so too were astronomy club memberships. Pushed forward by the “Dobsonian revolution” — the technology that allowed building simple telescopes with large mirrors — amateurs were discovering countless new targets to seek out in the sky. The anticipation for the long-awaited return of Halley’s Comet was building. And my little publication, Deep Sky, was now a quarterly. It had started as a monthly, first created on my dad’s chemistry office mimeograph machine, and now I huddled in a closet (figuratively!) one day a week working on it, cranking away on Astronomy the rest of the time. Its companion quarterly was Telescope Making, founded by Richard Berry to cover the equipment side of the hobby.

By the early 1980s, the magazine had evolved into a balanced and quite serious format. The science of astronomy got front-of-the-book treatment and hobby topics drifted toward the back, the two worlds separated by a central update on sky events for the month and a sprawling Star Dome evening sky map. The staff grew and evolved. We now had my fellow assistant editor Frank Reddy, Kate Bond was managing editor, and Robert Burnham had been promoted to senior editor. Our art director was Tom Hunt.

Coming under Kalmbach

Big change arrived in 1985, just as we were ramping up the excitement over Halley’s Comet. Our AstroMedia Corp. group, numbering about 40 people, functioned essentially as a big family — an extended astronomy club, if you will. Then Kalmbach Publishing Co., a company across town with multiple titles in other areas, bought us. At first, it seemed like we had been swallowed up by IBM. Kalmbach had perhaps 150 employees at that time, and functioned much more by the book than AstroMedia. We soon moved across town to spend several years in Kalmbach’s headquarters on Milwaukee’s 7th Street. The acquisition was of course very beneficial to Astronomy in numerous ways. Famous for its linchpin titles Model Railroader and Trains, Kalmbach gave us marketing strength our astronomical title had previously lacked.

Another of our brand’s longest serving and most valuable editors, Richard Talcott, joined the group. The apparition of Halley’s Comet gave the astronomy hobby a big boost. (Bright comets always do.) We had large issues with great coverage of the comet’s appearance, the science learned from it, and of course all the observational and astroimaging results. Great sadness prevailed, of course, with the explosion of space shuttle Challenger, but interest in astronomy, even as we moved from the Apollo era into the routine coverage of space shuttles, was white-hot.

And then we moved again: In 1990, Kalmbach shifted from Milwaukee out into the surrounding countryside, to a glass-and-steel building complex that was far more spacious and modern. We were in Waukesha, on the edge of an upscale suburb called Brookfield. And that is where the company, now known as Kalmbach Media Co., has been ever since.

The ’90s

The 1990s were filled with cool stories to cover. Spacecraft missions had us visit an asteroid and explore Mars and Jupiter in unprecedented detail — including sending the first rover, Sojourner, to visit another planet.

Comets were also a recurring theme during the ’90s. In 1993, astronomers Gene and Carolyn Shoemaker and David Levy discovered a comet that was destined to slam into Jupiter’s cloud tops. In 1994, that incredible event was visible in small telescopes and drew many new people to the hobby of backyard astronomy. Moreover, after a bit of a drought, two very bright comets graced our skies in 1995, 1996, and 1997. Comet Hale-Bopp was a physically huge comet and a bright naked-eye sight, visible for a long time, and Comet Hyakutake was also bright and wowed observers and imagers with an incredibly long tail.

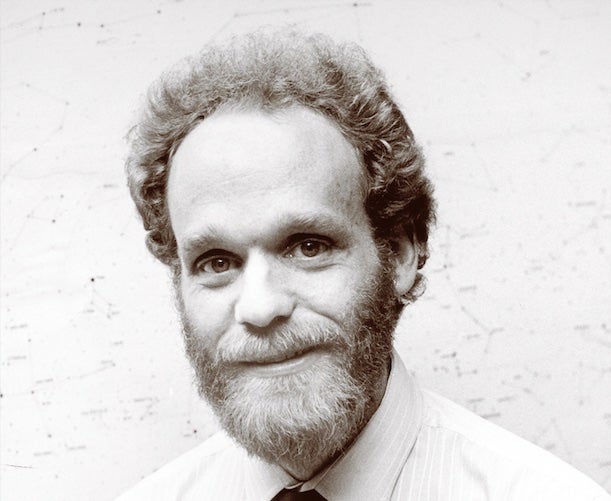

The 1990s also marked an era of major change at Astronomy. In 1992, Richard Berry left the magazine and Robert Burnham succeeded him as chief editor. Telescope Making was Richard’s baby, and so the company decided to end its publication, and also my quarterly Deep Sky with it. The company wanted me to focus exclusively on the larger Astronomy magazine. We also sold Odyssey, which had always been a bit of a challenge as a title aimed at kids on the periodical newsstand. We went from a four-title house to one focusing merely on the large title Steve Walther had begun.

It was a fun time on the magazine staff, but also one of considerable transition. Alan Dyer, Jeff Kanipe, Dave Bruning, and John Shibley were editors for a time; Rhoda Sherwood was a managing editor with a big personality. Steve Cole also served as managing editor before moving on. Bob Naeye and Tracy Staedter joined us as members of the team. When Robert Burnham decided to depart in 1996, a New York generalist, Bonnie Gordon, took over as editor. In a few weeks I went from associate editor to senior editor to managing editor.

Bonnie’s tenure lasted a few years, and in 2002 I was made the chief editor, and have been in that role now for more than 20 years.

Expanding science

The new millennium delivered an amazing and active era for the magazine. As we know, astronomy was accelerating into an time of exploration and discovery that had us scrambling to keep up. The Hubble Space Telescope’s countless findings, the exponential growth of discoveries of extrasolar planets, and a wide variety of findings on “big questions” gave us lots to adjust to. The age, size, and fate of the universe came into sharper view, as did the nature of black holes. We also experienced a resurgence of exploration of the solar system, with missions to Jupiter, Saturn and its moon Titan, the first landing on an asteroid, the first cometary material returned to Earth, and a campaign of more martian rovers. Once again the U.S. space program experienced tragedy, though, with the loss of the shuttle Columbia.

The magazine expanded its activities to create and develop its website, Astronomy.com, and covered a huge variety of science and hobby stories. Our staff during this period added such folks as managing editors Pat Lantier and Dick McNally, and another longtime and valuable editor, Michael E. Bakich. Robert Burnham also returned as a senior editor for a time, as did Frank Reddy. Our art director position evolved, including Carole Ross, Tom Ford, and LuAnn Williams Belter, who served for many years. And for many years, an extraordinarily talented illustrator, Elisabeth Roen Kelly, has produced diagrams that have enlivened the magazine’s pages.

Moving into the modern era

The 2010s saw the nature of discovery and exploration only accelerate. We had the first spacecraft that orbited Mercury, the winding down of the Space Shuttle Program, the discovery of gravitational waves, and the great Curiosity rover landing on Mars. A superb highlight came with the final step in the long-ago planned exploration of the major solar system when the New Horizons spacecraft flew past Pluto and its system of moons. The Voyagers, launched way back in the ’70s, made their way past the heliosphere, far out into deep space.

How could there be more? There was. We experienced the first spacecraft to orbit a comet, also sending a small lander onto the comet’s surface. And we witnessed the first image of the shadow of a black hole.

This incredible era in astronomy and astrophysics saw further changes in the Astronomy magazine staff. Our group of associate editors included Liz Kruesi, Bill Andrews, Sarah Scoles, Eric Betz, and Korey Haynes. Alison Klesman joined us as an associate editor and subsequently became a senior editor. Jake Parks came on as an associate editor and later became our digital editor. Our copy editor, Karri Stock, soon expanded her role into production editor. For years, our publisher was Kevin Keefe, a veteran who had been the editor of Trains magazine but who also had a passion for astronomy.

As we approached the pandemic era, things got a bit strange, as they did for everyone. The science of astronomy kept rocking, and the hobby experienced a renewal as people holed up at home looked to explore the cosmos from their backyards. We worked remotely for about two years, and I learned that I could have run Astronomy from anywhere — say, even the Moon.

Our current group came together on the cusp of the pandemic. Two of our most experienced and longest serving editors, Rich and Michael, retired. Longtime art director LuAnn also retired and was succeeded by Kelly Katlaps. I was the sole long-term employee left. Steve George, who serves as editor of our sister publication, Discover, and is also editorial vice president for the entire company, became a close colleague. A dynamo, Elisa Neckar is our senior production editor, and she keeps the work moving for both Astronomy and Discover. Not only did Alison become a senior editor, but we added Senior Editor Mark Zastrow and Editorial Assistant Samantha Hill. Most recently, Associate Editor Daniela Mata has joined us. We have a terrific, young, knowledgeable group that loves bringing you the best from the world of astronomy.

And the world of astronomy continues at high velocity, showing no signs of slowing down. In 2021, we experienced the first powered flight on another planet when the small helicopter Ingenuity flew around Mars. The first spacecraft to enter the Sun’s atmosphere, the Parker Solar Probe, returned incredible data. And although Hubble is still working, with NASA’s launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, we have now entered a new era of amazing discoveries that should last for 30 years.

The life of Astronomy magazine has been an amazing journey. With 50 years now in the books, one can only wonder about the incredible knowledge and experiences we’ll see in astronomy in the next 50 years. The magazine has been the largest-circulation title in the field for more than 40 of its 50 years. I know that it will continue on, reporting the most exciting discoveries and amazing things to see in the sky, in a unique and unprecedented way. And I hope you’ll be with us in this shared sense of discovery for many years to come.