Key Takeaways:

- Astronomy magazine, founded by Stephen Walther in 1973, initially targeted amateur astronomers with a less technical approach than existing publications.

- Through a strategic marketing campaign involving multiple mailings, the magazine rapidly gained subscribers, achieving financial stability and substantial growth within its first few years.

- The magazine's early team consisted of a small group, with Penny Oldenburger serving as a key operational leader and Richard Berry eventually becoming a long-term editor.

- Despite Stephen Walther's untimely death in 1977 from brain cancer, the magazine's success continued under Bob Maas's management, eventually leading to its acquisition by Kalmbach Publishing Co. in 1985 and the later addition of David Eicher to the editorial team.

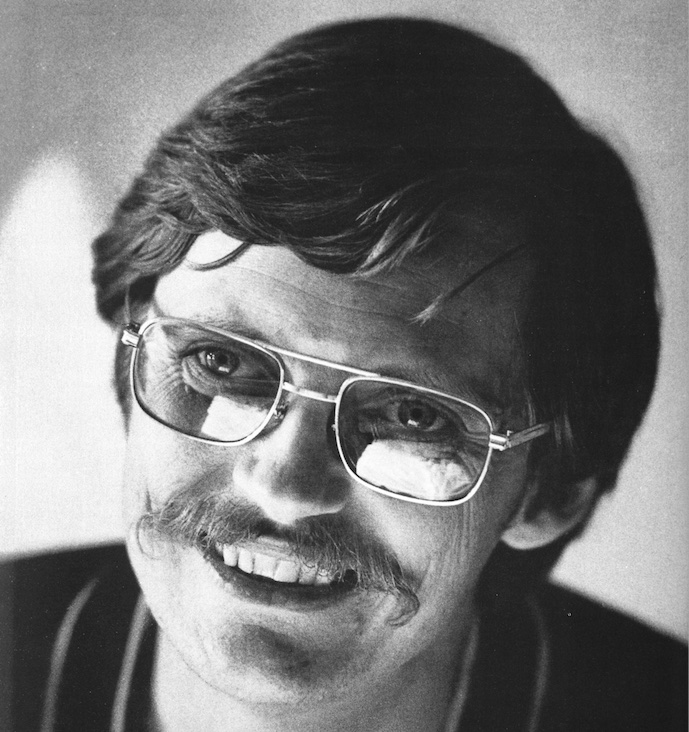

On May 27, 1973, a young journalist named Stephen Walther filed incorporation papers to begin publishing Astronomy magazine. The first issue was August 1973; by 1981, it was the largest-circulation title on the subject. It retains this distinction by a factor of two. Tragically, Stephen died a few years after the founding of the title. Here David Walther, older brother of Stephen, recounts Astronomy’s earliest days.

Stephen Andrew Walther, founder of Astronomy magazine, was born in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, July 22, 1944. From childhood, Stephen was passionate about amateur astronomy. His mother supported this astronomy interest, and to her despair, his struggle with mathematics was a roadblock to a career in what he loved most. He entered the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, and in time he found his outlet in the journalism department, where he created a blueprint for the publication of a magazine for amateur astronomers. After graduation, he came to Milwaukee, where he worked for a while in public relations. But he never lost his interest in the magazine, so after a few years he left his job and devoted all of his time to the creation of what would become Astronomy.

Stephen was an admirer of what was the most prominent astronomy magazine at the time, Sky & Telescope, but he felt that it was too technical to serve the needs of amateurs. He deeply believed that the amateur community provided an essential adjunct to professional astronomy, and that his magazine could best serve its needs.

Taking advice from his accounting firm, he created a subtle and complex model using testing and mail campaigns to get his magazine off the ground. An initial test mailing of 250,000 names returned a response for an initial issue with 14,000 subscribers. Additional short-term financing enabled a mailing to 1.5 million names, which built the subscription list to 31,000. That was enough for the magazine to survive, pay off debts, and build onward.

The magazine’s initial home was in a loftlike office over a seamstress shop on Mason Street in Milwaukee. The initial staff consisted of Stephen along with Penny Oldenburger and a few others. Penny was listed as managing editor. I saw her as Stephen’s chief assistant, and she ran all operations.

Later additions to the staff included Craig Brown (art director), Terence Steve Walther’s college project sparked a revolutionary idea. Dickinson (eastern regional editor), Richard Berry (technical editor), Henry Phillips (associate editor), Mary Jane Lamers (staff writer), and David Schwartz (production manager). Richard would continue on for many years as editor, while sadly Henry died quite young.

With additional staff, the team moved into a larger downtown space, at Broadway and Mason Street. It was a comfortable group of people with a good sense of humor. I remember the humorous way they treated the discovery that Uranus has rings.

At a very early date, David Eicher came to Stephen’s attention. He was impressed by what the teenager had created in his newsletter, Deep Sky Monthly, a publication for small-telescope observers. Stephen tried to coax David into joining the magazine. That did not happen during his lifetime.

Stephen collapsed in August 1976, at a celebration for staff and friends at Villa Terrace in Milwaukee. At first, his condition was diagnosed as work-related exhaustion. But later, X-rays revealed a terminal glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer.

Bob Maas was hired to run the company while Stephen was ill, which he did until Stephen’s death on Sept. 14, 1977. Bob continued running the company under my ownership thereafter.

What he contributed to the growth, management, and salvation of the magazine was invaluable and cannot be overstated.

David Eicher eventually joined Astronomy in 1982, fulfilling Stephen’s hope, and Bob Maas facilitated the sale of the magazine to Kalmbach Publishing Co. in 1985.