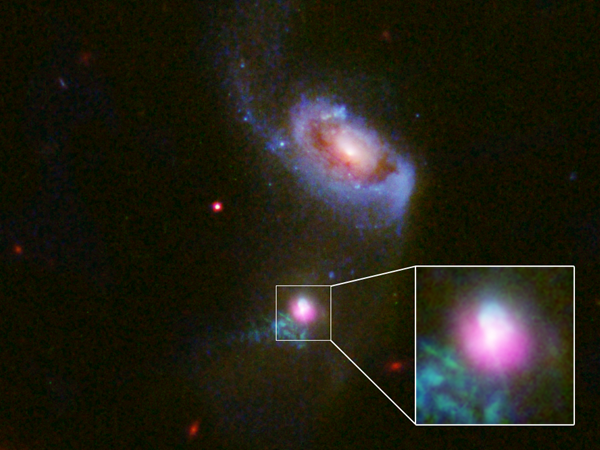

The team caught a supermassive black hole in the galaxy SDSS J1354+1327 (or J1354, for short) with a history of “snacking” on material in its vicinity, then letting out “burps” of energy as a result. In between meals, the black hole is relatively dormant. That dormant period lasted about 100,000 years, which is an eyeblink on cosmological timescales, but certainly not for humans. The work, presented at the Washington, D.C., meeting by Julie Comerford of the University of Colorado and published November 6 in The Astrophysical Journal, identifies two separate burps, or outflow events: one ancient burp on the verge of dissipating and one hinting at a much more recent meal. It is the first time two separate events have been identified for a single galaxy.

Two separate events

J1354 is a galaxy identified in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey; it sits about 800 million light-years away. Astronomers imaged J1354 in X-rays and optical light using the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the Hubble Space Telescope, the W.M. Keck Observatory, and the Apache Point Observatory. By combining the data from these different images, they spotted a large, diffuse “cone” of gas extending 30,000 light years below the bulge of the galaxy (where the supermassive black hole is located). This gas is ionized — meaning its atoms have been stripped of their electrons — by a huge burst of radiation from the supermassive black hole that occurred about 100,000 years ago.

An additional piece of the puzzle falls into place as one zooms out on the images of J1354 — the galaxy is located near a second, companion galaxy, which likely interacted with it in the past. The collision between the two galaxies then funneled material in toward the supermassive black hole and provided those large meals that prompted the burps.

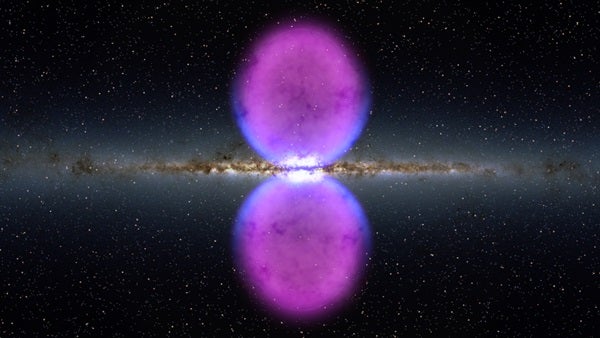

The Milky Way’s burp

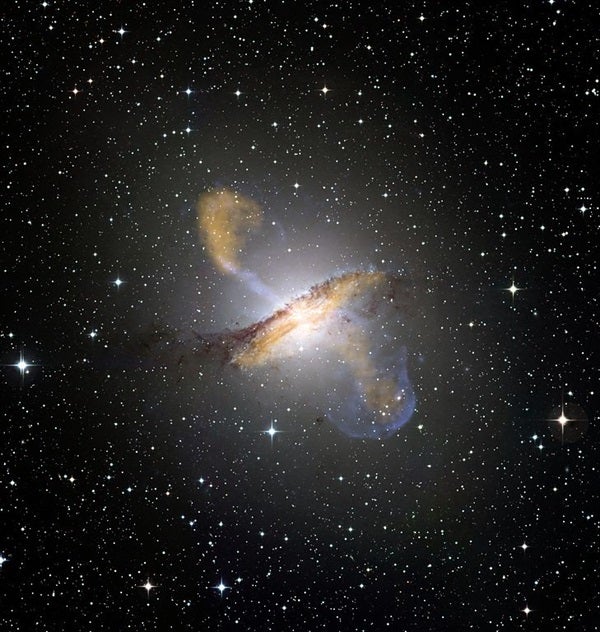

If you think this burping behavior is unique to distant (or other) galaxies, think again. This behavior is thought to be common for black holes, which should “flicker” on and off on 100,000-year timescales many times over the course of their existence. But while catching a single event isn’t necessarily rare, identifying the remnants of two past meals has never before happened. “Fortunately, we happened to observe this galaxy at a time when we could clearly see evidence for both events,” said Comerford in a press release.

Right now, both J1354 and the Milky Way’s supermassive black hole are experiencing what Comerford calls a “galactic food coma.” But that may change — “Our galaxy’s supermassive black hole is now napping after a big meal, just like J1354’s black hole has in the past. So we also expect our massive black hole to feast again, just as J1354’s has,” said Scott Barrows of CU.