These short-lived events depend on nice weather occurring on specific dates. But you can spy the best of April’s planets on any clear night. Venus and Jupiter dominate the evening scene, while Saturn appears at its best in the early morning hours.

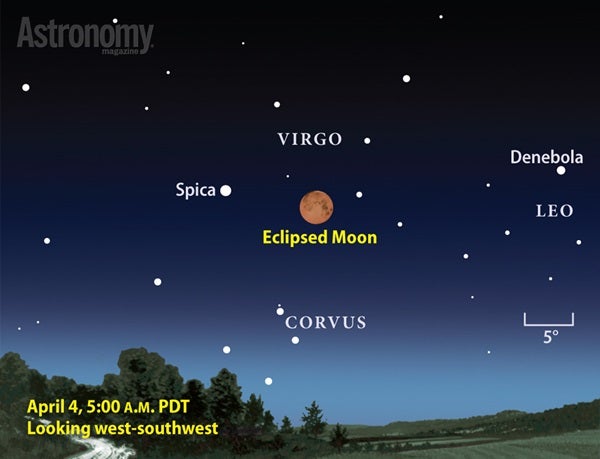

When it comes to record-setting events, the April 4 total lunar eclipse certainly ranks high. The Full Moon passes through Earth’s dark umbral shadow for 4 minutes and 43 seconds, which makes this the 21st century’s briefest view of totality. In fact, you need to go back to October 17, 1529, to find a shorter total lunar eclipse (only 1 minute and 41 seconds long).

From North America, better views of the eclipse come the farther west you live. From east of the Mississippi River, people will see only the eclipse’s initial partial phases during morning twilight. Everyone else will see totality, but the Moon will appear much higher and in a dark sky from the West Coast. The eclipse’s partial phases begin at 6:16 a.m. EDT (3:16 a.m. PDT), and totality starts at 4:58 a.m. PDT.

Let’s begin our tour of April planets in the western sky during evening twilight. Mars sets about 90 minutes after the Sun on the 1st and stands 5° above the horizon a half-hour later. It shines rather dimly at magnitude 1.4 and should show up to naked eyes, though binoculars certainly will help the cause. The Red Planet becomes increasingly hard to see as the month progresses and it dips lower in twilight.

Although Mercury passes behind the Sun on April 9, it reappears in the evening sky within 10 days. This starts the innermost planet’s best evening appearance of the year for Northern Hemisphere observers. It will reach its peak separation from the Sun in early May, but appears brighter in late April.

Mercury’s motion against the background stars continues through month’s end, and by the 30th, it reaches a point 1.7° south of the Pleiades star cluster (M45). The magnitude –0.4 planet then lies 7° high in the west-northwest an hour after sunset.

As Mercury swings toward Earth in late April, a telescope shows its increasing size and dwindling phase. On the 19th, the planet appears 6″ across and about 90 percent lit. By the 30th, its disk spans 7″ but sunlight illuminates less than 60 percent of it.

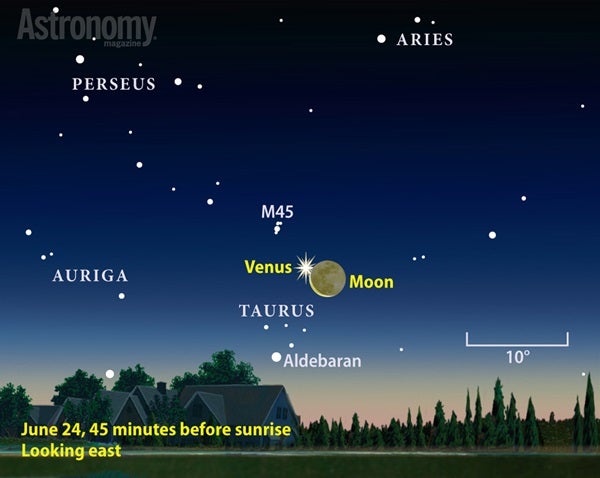

You won’t have any problem finding Venus even during bright twilight. The planet shines at magnitude –4.1 for most of April, a dazzling diamond hanging in the western sky for three hours after sunset. Venus begins the month in the constellation Aries but soon crosses into Taurus, where it remains the rest of the month. It passes 3° south of the Pleiades on April 10 and 7° north of 1st-magnitude Aldebaran, Taurus’ brightest star, on the 20th. The Bull’s luminary appears to be the brightest member of the V-shaped Hyades star cluster, though the star actually lies only half as far away.

You’ll want to be sure to catch the whole vista on the evening of the 20th. Not only is Venus 7° north of Aldebaran, but the waxing crescent Moon stands 7° west of the Hyades’ center. The arrangement of the Moon, Venus, Hyades, and Pleiades creates a beautiful scene as the sky darkens. The next evening isn’t too shabby either, with a noticeably fatter Moon standing 7° to the planet’s left.

Like Mercury, Venus’ telescopic appearance changes during April. The apparent diameter of its disk grows from 14″ to 17″ while the phase shrinks from 78 percent to 68 percent lit.

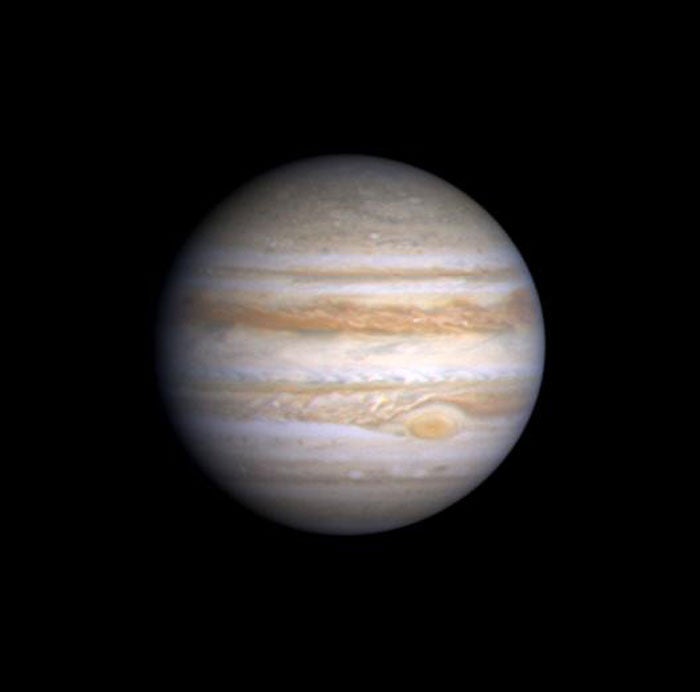

Swing a telescope toward Jupiter, and you’ll be quickly impressed with the rich detail visible in its cloud tops. The best views come in the early evening when the planet lies highest and its light passes through less of Earth’s turbulent atmosphere. The first things you’ll see are two parallel dark belts that straddle a brighter zone tracing the planet’s 40″-diameter equator. A whole series of light zones and darker belts appears on nights with steady seeing.

Once you’ve studied Jupiter’s atmosphere for a while, turn your attention to the planet’s family of moons. Typically Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto show up as bright dots beside the planet and lined up with the jovian equator. Occasionally, however, one or more hide behind Jupiter or transit directly in front of the planet. In the latter case, the moon also drops its shadow onto the planet’s cloud tops.

The four moons appear in order of increasing distance (Io through Callisto) to Jupiter’s west after midnight April 2/3. This alignment follows an earlier transit of Io and its shadow across the planet’s face. The transit begins at 12:04 a.m. EDT followed about an hour later by the shadow.

After Io and its shadow leave Jupiter’s disk (at 2:21 a.m. and 3:26 a.m. EDT, respectively), you may notice another alignment in the works. Io passes just 1.4″ south of Europa at 4:32 a.m. EDT. And about 90 minutes later, Io eclipses Europa. Observers in western North America can see Europa dim for six minutes starting at 3:06 a.m. PDT.

This eclipse is part of a rare series of mutual events among the four Galilean satellites. They occur when the orbits of the moons turn edge-on to the Sun and Earth, which happens twice during Jupiter’s 12-year circuit of the Sun. One moon may pass in front of another (an occultation), or one may cast its shadow on another (an eclipse). The current series will run through August.

The last bright planet rises around 11:30 p.m. local daylight time in early April and two hours sooner by month’s end. Saturn lies low in the southeast by midnight and appears about a third of the way from the southern horizon to the zenith shortly before morning twilight begins. The planet shines at magnitude 0.2, significantly brighter than any star in its host constellation, Scorpius. Only 1st-magnitude Antares, located 9° southeast of Saturn, comes close.

Saturn moves slowly westward relative to the starry background this month as it approaches opposition and peak visibility in late May. It stands 0.5° north of 4th-magnitude Nu (ν) Scorpii on April 1. By the 30th, it has slid to a position 1.2° north of 2nd-magnitude Beta (β) Sco.

Any telescope will deliver spectacular views of Saturn and its rings. The planet’s disk measures 18″ across at midmonth and likely will appear bland. But few observers will be able to take their eyes off the stunning rings, which span 41″ and tilt 25° to our line of sight.

You’ll also see Saturn’s biggest and brightest moon, 8th-magnitude Titan, through any scope. You can find it due north of the planet April 2 and 18 and due south April 10 and 26. Three other moons — Tethys, Dione, and Rhea — glow at 10th magnitude and show up through 4-inch and larger instruments. All orbit inside Titan and thus change positions from night to night.

Although Uranus and Neptune are both morning objects, neither climbs high enough before dawn to merit a look. You’re better off waiting a couple of months for better views.

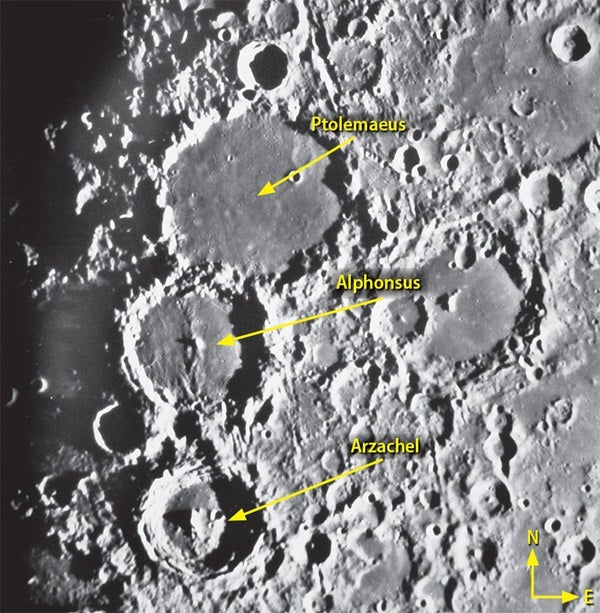

The endearing couple of Terra and Luna glides quietly across the solar system’s dance floor every month. From our earthly perspective, the Moon appears to circle us, at times leading and then following, but it actually never moves backward relative to the audience of stars. What it does do is change speeds as its distance from Earth changes, initiating a dance astronomers call “libration.” If you concentrate on our neighbor’s face during April, you can see this libration as the phases wax and wane.

Start with the crater Byrgius, which resides in the Moon’s southwestern corner. Although this 54-mile-wide impact feature doesn’t stand out, a much smaller crater on its eastern rim does. The youngster Byrgius A boasts a bright ray system that appears quite prominent even through binoculars. Each night after the April 4 Full Moon, this dazzling dimple rotates into better view because the Moon is moving more slowly than normal, letting us peek a bit past its normal southwestern limb.

We swap places during the passage through New Moon and arrive at First Quarter on April 25 getting great views of the opposite limb. Using binoculars on the 25th or 26th, look for a trio of dark spots on the northeastern limb: Lacus Spei, Endymion, and Mare Humboldtianum.

With each step toward the next Full phase, Luna moves more slowly than usual and the trio rotates away from us. Mare Humboldtianum will disappear May 1, while the other two reach the limb at Full Moon on May 3. But by that time, Byrgius A has spun back into view.

Although we’ve come back to the same spot relative to the Sun’s spotlight, Luna’s more involved dance does not repeat exactly. That grander cycle takes some 18 years to complete.

We’re already four months into the new year, and the skies still haven’t delivered a good meteor show. A Full Moon blasted January’s Quadrantids, and we’ve had only minor showers since. But that changes the night of April 22/23 when the annual Lyrid meteor shower reaches its peak. The waxing crescent Moon sets around midnight local daylight time, which leaves the prime viewing hours before dawn Moon-free.

Although the Lyrids typically deliver between 15 and 20 meteors per hour at their peak for observers at excellent sites, this year could be better. Some meteor scientists predict enhanced rates in 2015, so it could pay dividends to be watching before dawn April 23.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mercury (west) |

Jupiter (west) |

Saturn (southwest) |

| Venus (west) |

Saturn (southeast) |

Uranus (east) |

| Mars (west) |

Neptune (east) |

|

| Jupiter (south) |

|

|

| |

||

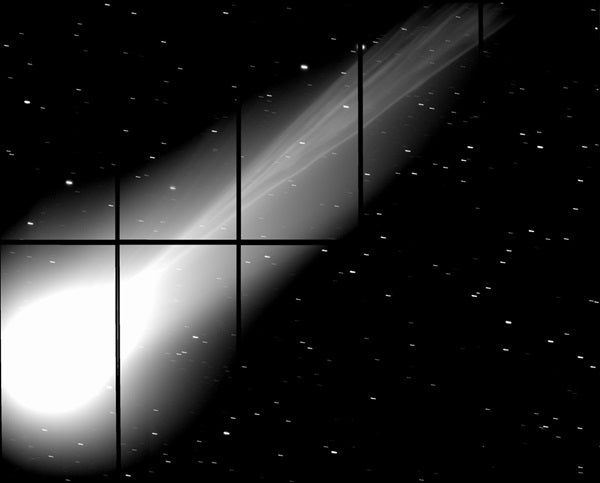

The inner solar system hosts a never-ending parade of periodic comets. The star of these local objects is the infrequent visitor 1P/Halley, but few others give rise to much interest. Luckily, the once-only renegades from the distant Oort Cloud can prove quite entertaining. That’s what happened early this year with Comet Lovejoy (C/2014 Q2). This fresh comet brightened unexpectedly to 4th magnitude in January and put on a nice show for anyone who braved the cold.

If the more optimistic predictions hold, Comet Lovejoy still might be an 8th-magnitude object in April, but don’t be surprised if it’s a couple of magnitudes fainter. If it is on the fainter side, you’ll need a 6-inch scope under a dark sky to detect the ghostly puffball. Target the time around midmonth when the Moon interferes least. On the plus side, Lovejoy remains visible all night as it drifts in front of Cassiopeia’s stars.

The comet’s dust output likely is shutting down as the dirty snowball heads away from the Sun, so Lovejoy should appear small and round. Bump the magnification up to 150x or more to see detail. Can you spy the false nucleus — a dot of bright light at the comet’s center — through the thinning layers of gas and dust?

Let Comet 88P/Howell serve as a backup plan. This periodic visitor comes closest to the Sun in early April and could grow brighter than 10th magnitude. Howell moves slowly through Aquarius this month, which means it’s best placed for more southerly observers. Messier marathoners will understand the challenge right away: Howell lies near M30, typically the toughest object at the end of a long night’s observing.

Main-belt asteroid 44 Nysa shows up well through a 3-inch telescope from the country or a 6-inch scope from the suburbs in April. The 44-mile-wide space rock lies about halfway up in the southeastern sky during evening hours. You can find the right area easily. Start with the bright tail star of Leo, magnitude 2.1 Denebola, and then drop 8° due south to 4th-magnitude Nu (ν) Virginis. Nysa lies within 5° of Nu all month.

It won’t be hard to track the asteroid, but it will require attention to detail. Western Virgo has a sprinkling of stars with a nice range of magnitudes, a real help when trying to locate 10th-magnitude Nysa. On the evenings of April 23–27, a distinctive trapezoid of stars makes a perfect background for seeing the solar system object’s night-to-night movement. The asteroid lies out in the open the rest of the month, so it should be easy pickings except when the Moon is nearby through April 4 and after the 27th.

German-French astronomer Hermann Goldschmidt discovered Nysa in May 1857. By the time he was done four years later, Goldschmidt had 14 asteroids to his credit, the record at that time. In Greek mythology, Nysa was the homeland of the Hyades nymphs.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.