The planet Venus is well-known for its thick carbon dioxide atmosphere and oven-hot surface, and as a result, it is often portrayed as Earth’s inhospitable evil twin.

But in a new analysis based on five years of observations using the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Venus Express, scientists have uncovered a chilly layer at temperatures of around – 283° Fahrenheit (–175° Celsius) in the atmosphere 78 miles (125 kilometers) above the planet’s surface. The curious cold layer is far frostier than any part of Earth’s atmosphere, despite Venus being much closer to the Sun.

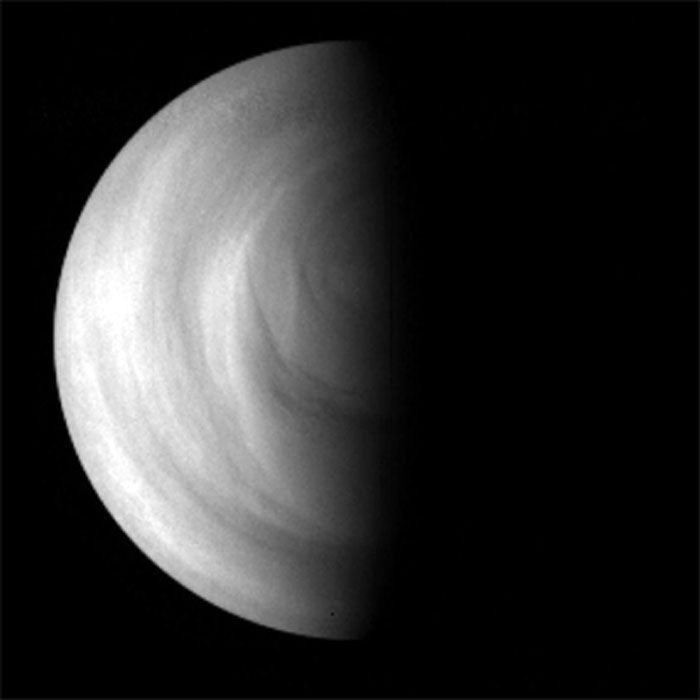

Scientists made the discovery by watching as light from the Sun filtered through the atmosphere to reveal the concentration of carbon dioxide gas molecules at various altitudes along the terminator — the dividing line between the day and night sides of the planet.

Armed with information about the concentration of carbon dioxide combined with data on atmospheric pressure at each height, scientists could then calculate the corresponding temperatures. “Since the temperature at some heights dips below the freezing temperature of carbon dioxide, we suspect that carbon dioxide ice might form there,” said Arnaud Mahieux of the Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy.

Clouds of small carbon dioxide ice or snow particles should be very reflective, perhaps leading to brighter than normal sunlight layers in the atmosphere. “However, although Venus Express, indeed, occasionally observes very bright regions in the venusian atmosphere that could be explained by ice, they could also be caused by other atmospheric disturbances, so we need to be cautious,” said Mahieux.

The study also found that the cold layer at the terminator is sandwiched between two comparatively warmer layers. “The temperature profiles on the hot day side and cool night side at altitudes above 75 miles (120km) are extremely different, so at the terminator we are in a regime of transition with effects coming from both sides,” said Mahieux. “The night side may be playing a greater role at one given altitude, and the day side might be playing a larger role at other altitudes.”

Similar temperature profiles along the terminator have been derived from other Venus Express datasets, including measurements taken during the transit of Venus earlier this year.

Models are able to predict the observed profiles, but further confirmation will be provided by examining the role played by other atmospheric species, such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen, and oxygen, which are more dominant than carbon dioxide at high altitudes. “The finding is very new, and we still need to think about and understand what the implications will be,” said Håkan Svedhem, ESA’s Venus Express project scientist. “But it is special, as we do not see a similar temperature profile along the terminator in the atmospheres of Earth or Mars, which have different chemical compositions and temperature conditions.”

The planet Venus is well-known for its thick carbon dioxide atmosphere and oven-hot surface, and as a result, it is often portrayed as Earth’s inhospitable evil twin.

But in a new analysis based on five years of observations using the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Venus Express, scientists have uncovered a chilly layer at temperatures of around – 283° Fahrenheit (–175° Celsius) in the atmosphere 78 miles (125 kilometers) above the planet’s surface. The curious cold layer is far frostier than any part of Earth’s atmosphere, despite Venus being much closer to the Sun.

Scientists made the discovery by watching as light from the Sun filtered through the atmosphere to reveal the concentration of carbon dioxide gas molecules at various altitudes along the terminator — the dividing line between the day and night sides of the planet.

Armed with information about the concentration of carbon dioxide combined with data on atmospheric pressure at each height, scientists could then calculate the corresponding temperatures. “Since the temperature at some heights dips below the freezing temperature of carbon dioxide, we suspect that carbon dioxide ice might form there,” said Arnaud Mahieux of the Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy.

Clouds of small carbon dioxide ice or snow particles should be very reflective, perhaps leading to brighter than normal sunlight layers in the atmosphere. “However, although Venus Express, indeed, occasionally observes very bright regions in the venusian atmosphere that could be explained by ice, they could also be caused by other atmospheric disturbances, so we need to be cautious,” said Mahieux.

The study also found that the cold layer at the terminator is sandwiched between two comparatively warmer layers. “The temperature profiles on the hot day side and cool night side at altitudes above 75 miles (120km) are extremely different, so at the terminator we are in a regime of transition with effects coming from both sides,” said Mahieux. “The night side may be playing a greater role at one given altitude, and the day side might be playing a larger role at other altitudes.”

Similar temperature profiles along the terminator have been derived from other Venus Express datasets, including measurements taken during the transit of Venus earlier this year.

Models are able to predict the observed profiles, but further confirmation will be provided by examining the role played by other atmospheric species, such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen, and oxygen, which are more dominant than carbon dioxide at high altitudes. “The finding is very new, and we still need to think about and understand what the implications will be,” said Håkan Svedhem, ESA’s Venus Express project scientist. “But it is special, as we do not see a similar temperature profile along the terminator in the atmospheres of Earth or Mars, which have different chemical compositions and temperature conditions.”