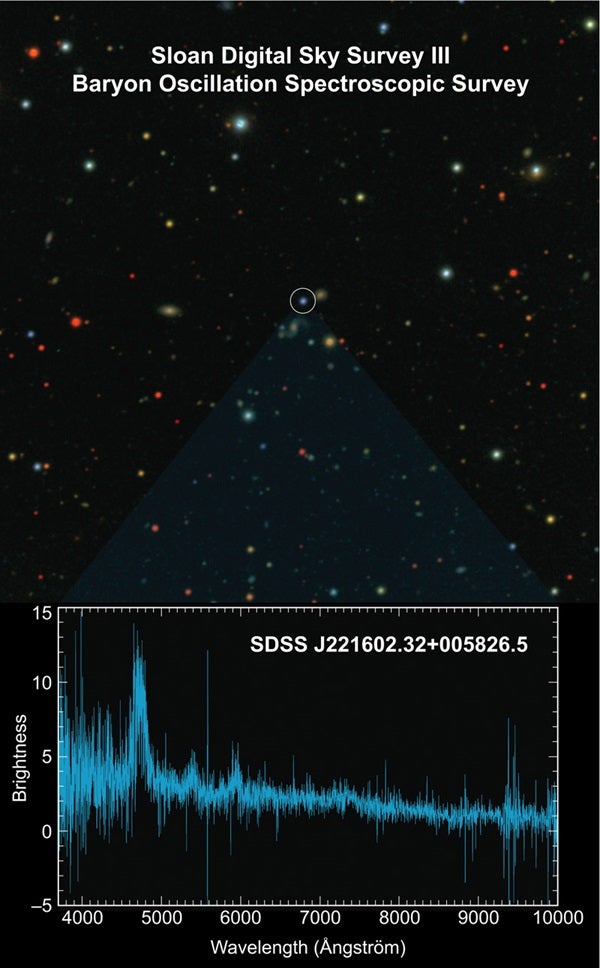

The most ambitious attempt yet to trace the history of the universe has seen “first light.” The Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (BOSS), a part of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey III (SDSS-III), took its first astronomical data September 14-15 after years of preparations.

That night, astronomers used the Sloan Foundation 2.5-meter telescope at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico to measure the spectra of a thousand galaxies and quasars, thus starting a quest to eventually collect spectra for 1.4 million galaxies and 160,000 quasars by 2014.

“The data from BOSS will be the best obtained on the large-scale structure of the universe,” said David Schlegel, principal investigator of BOSS at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. BOSS uses the same telescope as the original Sloan Digital Sky Survey, but equipped with new spectrographs to measure the spectra. “The new spectrographs are more efficient in infrared light,” said Natalie Roe, the instrument scientist for BOSS at the Berkeley Lab. “The light emitted by distant galaxies arrives at Earth as infrared light, so these improved spectrographs are able to look much farther back in time.”

The ability to look farther back in time is important in allowing BOSS to take advantage of a feature in the universe called “baryon oscillations.” Baryon oscillations began when pressure waves traveled through the early universe.

“Like sound waves passing through air, the waves push some of the matter closer together as they travel,” said Nikhil Padmanabhan, a BOSS researcher. “In the early universe, these waves were moving at half the speed of light, but when the universe was only a few hundred thousand years old, the universe cooled enough to halt the waves, leaving a signature 500 million light-years in length.”

“We can see these frozen waves in the distribution of galaxies today,” said Daniel Eisenstein, director of the SDSS-III at the University of Arizona. “By measuring the length of the baryon oscillations, we can determine how dark energy has affected the expansion history of the universe. That in turn helps us figure out what dark energy could be.”

“Studying baryon oscillations is an exciting method for measuring dark energy in a way that’s complementary to techniques in supernova cosmology,” said Kyle Dawson at the University of Utah, who is leading the commissioning of BOSS. “BOSS’ galaxy measurements will be a revolutionary dataset that will provide rich insights into the universe,” said Martin White, BOSS’ survey scientist at the Berkeley Lab.

BOSS’ first data were taken after many nights of clouds and rain. The first data came from a region of sky in the constellation Aquarius. “Looks like I’m in for a very hectic but extremely exciting first month on the job,” said Nic Ross who has just joined the Berkeley Lab.

The BOSS spectrographs will work with more than two thousand large metal plates that are placed at the focal plane of the telescope. These plates are drilled with the precise locations of nearly two million objects across the northern sky. Optical fibers plugged into a thousand tiny holes in each of these “plug plates” carry the light from each observed galaxy or quasar to BOSS’ new spectrographs.

Using these plug plates for the first light image should have been easy, but it didn’t quite turn out the way astronomers planned. “In our first test images, it looked like we’d just taken random spectra from all over,” Schlegel said. “After some hair-pulling, the problem turned out to be simple. After we flipped the plus and minus signs in the program, everything worked perfectly.”

The first public data release from SDSS-III is planned for December 2010 under the watchful eye of Mike Blanton at the New York University. “Making high-quality astronomical data available to all on the Web continues to revolutionize astronomical science and education by taking advantage of the talents of not just our team, but of all astronomers and also the general public.”