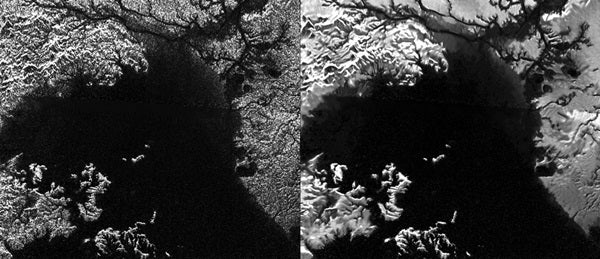

Thanks to a recently developed technique for handling noise in Cassini’s radar images, these views now have a whole new look. The technique, referred to by its developers as “despeckling,” produces images of Titan’s surface that are much clearer and easier to look at than the views to which scientists and the public have grown accustomed.

Typically, Cassini’s radar images have a characteristic grainy appearance. This “speckle noise” can make it difficult for scientists to interpret small-scale features or identify changes in images of the same area taken at different times. Despeckling uses an algorithm to modify the noise, resulting in clearer views that can be easier for researchers to interpret.

Antoine Lucas got the idea to apply this new technique while working with members of Cassini’s radar team when he was at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

“Noise in the images gave me headaches,” said Lucas, who now works at the astrophysics division of France’s nuclear center (CEA). Knowing that mathematical models for handling the noise might be helpful, Lucas searched through research published by that community, which is somewhat disconnected from people working directly with scientific data. He found that a team near Paris was working on a “denoising” algorithm, and he began working with them to adapt their model to the Cassini radar data. The collaboration resulted in some new and innovative analysis techniques.

“My headaches were gone, and more importantly, we were able to go further in our understanding of Titan’s surface using the new technique,” Lucas said.

As helpful as the tool has been, for now, it is being used selectively.

“This is an amazing technique, and Antoine has done a great job of showing that we can trust it not to put features into the images that aren’t really there,” said Randy Kirk, a Cassini radar team member from the U.S. Geologic Survey in Flagstaff, Arizona. Kirk said the radar team is going to have to prioritize which images are the most important to applying the technique. “It takes a lot of computation, and at the moment quite a bit of ‘fine-tuning’ to get the best results with each new image, so for now we’ll likely be despeckling only the most important — or most puzzling — images,” Kirk said.

Despeckling Cassini’s radar images has a variety of scientific benefits. Lucas and colleagues have shown that they can produce 3-D maps, called digital elevation maps, of Titan’s surface with greatly improved quality. With clearer views of river channels, lake shorelines, and windswept dunes, researchers are also able to perform more precise analyses of processes shaping Titan’s surface. And Lucas suspects that the speckle noise itself, when analyzed separately, may hold information about properties of the surface and subsurface.

“This new technique provides a fresh look at the data, which helps us better understand the original images,” said Stephen Wall from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “With this innovative new tool, we will look for details that help us to distinguish among the different processes that shape Titan’s surface,” he said.