Ancient light absorbed by neutral hydrogen atoms could be used to test certain predictions of string theory, say cosmologists at the University of Illinois. Making the measurements, however, would require a gigantic array of radio telescopes to be built on Earth, in space or on the Moon.

String theory, a theory whose fundamental building blocks are tiny one-dimensional filaments called strings, is the leading contender for a “theory of everything.” Such a theory would unify all four fundamental forces of nature (the strong and weak nuclear forces, electromagnetism, and gravity). But finding ways to test string theory has been difficult.

Now, cosmologists at the U of I say absorption features in the 21-centimeter spectrum of neutral hydrogen atoms could be used for such a test.

“High-redshift, 21-centimeter observations provide a rare observational window in which to test string theory, constrain its parameters and show whether or not it makes sense to embed a type of inflation, called brane inflation, into string theory,” says Benjamin Wandelt, a professor of physics and of astronomy at the U of I.

“If we embed brane inflation into string theory, a network of cosmic strings is predicted to form,” Wandelt says. “We can test this prediction by looking for the impact this cosmic string network would have on the density of neutral hydrogen in the universe.”

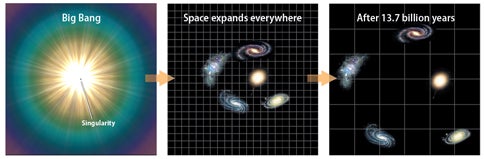

About 400,000 years after the Big Bang, the universe consisted of a thick shell of neutral hydrogen atoms (each composed of a single proton orbited by a single electron) illuminated by what became known as the cosmic microwave background.

Because neutral hydrogen atoms readily absorb electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength of 21 centimeters, the cosmic microwave background carries a signature of density perturbations in the hydrogen shell, which should be observable today, Wandelt says.

Cosmic strings are filaments of infinite length. Their composition can be loosely compared to the boundaries of ice crystals in frozen water. When water in a bowl begins to freeze, ice crystals will grow at different points in the bowl, with random orientations. When the ice crystals meet, they usually will not be aligned to one another. The boundary between two such misaligned crystals is called a discontinuity or a defect.

Cosmic strings are defects in space. A network of strings is predicted by string theory (and also by other supersymmetric theories known as Grand Unified Theories, which aspire to unify all known forces of nature except gravity) to have been produced in the early universe, but has not been detected so far.

Cosmic strings produce characteristic fluctuations in the gas density through which they move, a signature of which will be imprinted on the 21-centimeter radiation.

The cosmic string network predicted to occur with brane inflation could be tested by looking for the corresponding fluctuations in the 21-centimeter radiation. Like the cosmic microwave background, the cosmological 21-centimeter radiation has been stretched as the universe has expanded. Today, this relic radiation has a wavelength closer to 21 meters, putting it in the long-wavelength radio portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

To precisely measure perturbations in the spectra would require an array of radio telescopes with a collective area of more than 1,000 square kilometers. Such an array could be built using current technology, Wandelt says, but would be prohibitively expensive.

If such an enormous array were eventually constructed, measurements of perturbations in the density of neutral hydrogen atoms could also reveal the value of string tension, a fundamental parameter in string theory, Wandelt says. “And that would tell us about the energy scale at which quantum gravity begins to become important.”