A type Ia supernova forms when a white dwarf star — the leftover cinder of a star like our Sun — accumulates so much mass from a companion star that it reignites its collapsed stellar furnace and detonates, briefly outshining all other stars in its host galaxy. Because these stellar explosions have a characteristic brightness, astronomers use them to calculate cosmic distances. (It was by studying type Ia supernovae that two independent research teams determined that the expansion of the universe was accelerating, earning them the 2011 Nobel Prize in physics.)

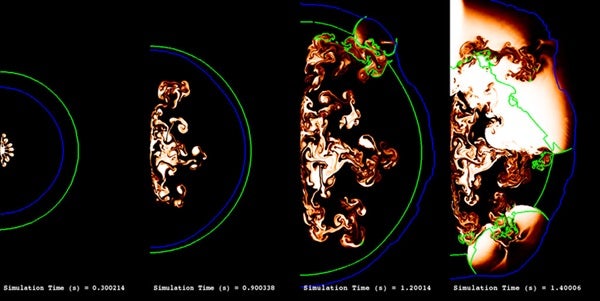

To better understand the complex conditions driving this type of supernova, the researchers performed new 3-D calculations of the turbulence that is thought to push a slow-burning flame past its limits, causing a rapid detonation — the so-called deflagration-to-detonation transition (DDT). How this transition might occur is hotly debated, and these calculations provide insights into what is happening at the moment when the white dwarf star makes this spectacular transition to a supernova. “Turbulence properties inferred from these simulations provide insight into the DDT process, if it occurs,” said Aaron Jackson from the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C.

While the deflagration-detonation transition mechanism is still not well understood, a prevailing hypothesis in the astrophysics community is that if turbulence is intense enough, DDT will occur. Extreme turbulent intensities inferred in the white dwarf from the researchers’ simulations suggest DDT is likely, but the lack of knowledge about the process allows a large range of outcomes from the explosion. Matching simulations to observed supernovae can identify likely conditions for DDT.

“There are a few options for how to simulate how [supernovae] might work, each of which has different advantages and disadvantages,” said Dean Townsley from the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa. “Our goal is to provide a more realistic simulation of how a given supernova scenario will perform, but that is a long-term goal and involves many different improvements that are still in progress.”

The researchers speculate that this better understanding of the physical underpinnings of the explosion mechanism will give us more confidence in using type Ia supernovae as standard candles and may yield more precise distance estimates.

A type Ia supernova forms when a white dwarf star — the leftover cinder of a star like our Sun — accumulates so much mass from a companion star that it reignites its collapsed stellar furnace and detonates, briefly outshining all other stars in its host galaxy. Because these stellar explosions have a characteristic brightness, astronomers use them to calculate cosmic distances. (It was by studying type Ia supernovae that two independent research teams determined that the expansion of the universe was accelerating, earning them the 2011 Nobel Prize in physics.)

To better understand the complex conditions driving this type of supernova, the researchers performed new 3-D calculations of the turbulence that is thought to push a slow-burning flame past its limits, causing a rapid detonation — the so-called deflagration-to-detonation transition (DDT). How this transition might occur is hotly debated, and these calculations provide insights into what is happening at the moment when the white dwarf star makes this spectacular transition to a supernova. “Turbulence properties inferred from these simulations provide insight into the DDT process, if it occurs,” said Aaron Jackson from the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C.

While the deflagration-detonation transition mechanism is still not well understood, a prevailing hypothesis in the astrophysics community is that if turbulence is intense enough, DDT will occur. Extreme turbulent intensities inferred in the white dwarf from the researchers’ simulations suggest DDT is likely, but the lack of knowledge about the process allows a large range of outcomes from the explosion. Matching simulations to observed supernovae can identify likely conditions for DDT.

“There are a few options for how to simulate how [supernovae] might work, each of which has different advantages and disadvantages,” said Dean Townsley from the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa. “Our goal is to provide a more realistic simulation of how a given supernova scenario will perform, but that is a long-term goal and involves many different improvements that are still in progress.”

The researchers speculate that this better understanding of the physical underpinnings of the explosion mechanism will give us more confidence in using type Ia supernovae as standard candles and may yield more precise distance estimates.