Unlike our solitary Sun, most stars form in binary pairs — two stars that are in orbit around each other. Binary stars are very common, but they pose a number of questions, including how and where planets form in such complex environments.

“ALMA has now given us the best view yet of a binary star system sporting protoplanetary disks, and we find that the disks are mutually misaligned!” said Eric Jensen from Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania.

The two stars in the HK Tauri system, which is located about 450 light-years from Earth in the constellation Taurus the Bull, are less than 5 million years old and separated by about 36 billion miles (58 billion kilometers) — this is 13 times the distance of Neptune from the Sun.

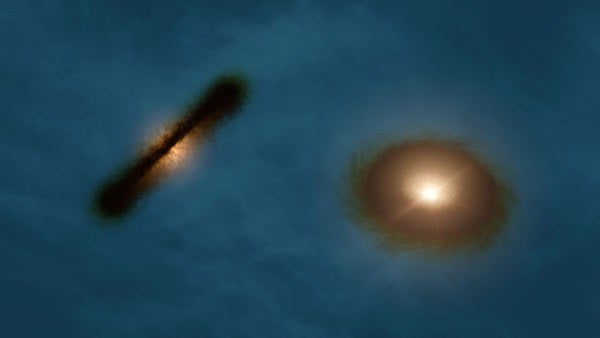

The fainter star, HK Tauri B, is surrounded by an edge-on protoplanetary disk that blocks the starlight. Because the glare of the star is suppressed, astronomers can easily get a good view of the disk by observing in visible light or at near-infrared wavelengths.

The companion star, HK Tauri A, also has a disk, but in this case it does not block out the starlight. As a result, the disk cannot be seen in visible light because its faint glow is swamped by the dazzling brightness of the star. But it does shine brightly in millimeter-wavelength light, which ALMA can readily detect.

Using ALMA, the team was not only able to see the disk around HK Tauri A, but also they could measure its rotation for the first time. This clearer picture enabled the astronomers to calculate that the two disks are out of alignment with each other by at least 60°. So rather than being in the same plane as the orbits of the two stars, at least one of the disks must be significantly misaligned.

“This clear misalignment has given us a remarkable look at a young binary star system,” said Rachel Akeson from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “Although there have been earlier observations indicating that this type of misaligned system existed, the new ALMA observations of HK Tauri show much more clearly what is really going on in one of these systems.”

Stars and planets form out of vast clouds of dust and gas. As material in these clouds contracts under gravity, it begins to rotate until most of the dust and gas falls into a flattened protoplanetary disk swirling around a growing central protostar.

But in a binary system like HK Tauri, things are much more complex. When the orbits of the stars and the protoplanetary disks are not roughly in the same plane, any planets that may be forming can end up in highly eccentric and tilted orbits.

“Our results show that the necessary conditions exist to modify planetary orbits and that these conditions are present at the time of planet formation, apparently due to the formation process of a binary star system,” said Jensen. “We can’t rule other theories out, but we can certainly rule in that a second star will do the job.”

Since ALMA can see the otherwise invisible dust and gas of protoplanetary disks, it allowed for never-before-seen views of this young binary system. “Because we’re seeing this in the early stages of formation with the protoplanetary disks still in place, we can see better how things are oriented,” said Akeson.

Looking forward, the researchers want to determine if this type of system is typical or not. They note that this is a remarkable individual case, but additional surveys are needed to determine if this sort of arrangement is common throughout our home galaxy.

“Although understanding this mechanism is a big step forward, it can’t explain all of the weird orbits of extrasolar planets — there just aren’t enough binary companions for this to be the whole answer,” said Jensen. “So that’s an interesting puzzle still to solve, too!”